A new study published in the journal Scientific Reports has revealed that baby pterosaurs could most likely fly almost as soon as they hatched from their eggs. Pterosaurs were flying reptiles that lived at the same time as the dinosaurs, more than 200 million years ago, and they were the first flying creatures to appear on the planet.

“We’re not the first people to say this,” study co-author Darren Naish, an independent paleontologist and public science educator, told New Scientist. “The main strength of our study is it’s combining several different lines of evidence.”

The Debate About Young Pterosaurs And Flight Finally Settled

The “we” he refers to are himself, Dr. Mark Witton from the University of Portsmouth, and Dr. Liz Martin-Silverstone from the University of Bristol. The three paleontologists teamed up to study the flight capabilities of hatchling pterosaurs, which would have looked like extremely miniaturized versions of their parents.

Skeletal restorations of pterosaur taxa (hatchlings and adults) used in the recent study. (A) Sinopterus dongi hatchling; (B) S. dongi hatchling compared to adult; (C) Pterodaustro guinazui hatchling; (D) hatchling compared with adult. White shading indicates well-represented bones requiring no or only minimal reconstruction, grey shading indicates elements which are represented in fossils but are difficult to reconstruct accurately. (Scientific Reports)

Besides being the first creatures to ever fly, the pterosaurs were also the largest animals to ever develop that capacity. One type of pterosaur, known as Quetzalcoatlus, had a 33-foot (10-meter) wingspan when fully grown. But baby pterosaurs would have been miniscule in comparison to their parents, so small they could have been easily picked up and held in a human being’s hand.

There has been an ongoing dispute among paleontologists about whether hatchling pterosaurs could fly soon after birth. One group argued they wouldn’t have been able to fly right away and would have needed at least a few weeks to develop to the point where they could. But a second group were convinced they would have been able to take flight right away, much as many reptiles today are able to live independently from their parents as soon as they break out of their eggs.

This unusual dinosaur question may have finally been settled, thanks to the careful analysis performed by the UK-based researchers. They examined fossilized bones of three young Pterodaustro guinazui and one young Sinopterus dongi, a pair of closely related pterosaur species. They checked the wing bones for strength and wingspan, making comparisons with the fossilized wing bones of 22 adult pterosaurs.

Based on the results of this detailed anatomical study, they concluded that newborn pterosaurs possessed wings that would have been well-prepared for immediate flight. No training or developmental period would have been necessary.

Some had suggested that perhaps young pterosaurs could glide at birth, but not flap their wings to attain greater heights. The results of this study show that this idea was not correct, and that their flying abilities would have been quite advanced from the beginning.

So how quickly would they have been prepared to leap from their nests and take flight?

“My gut feeling is minutes, but certainly within hours of hatching,” Darren Naish said.

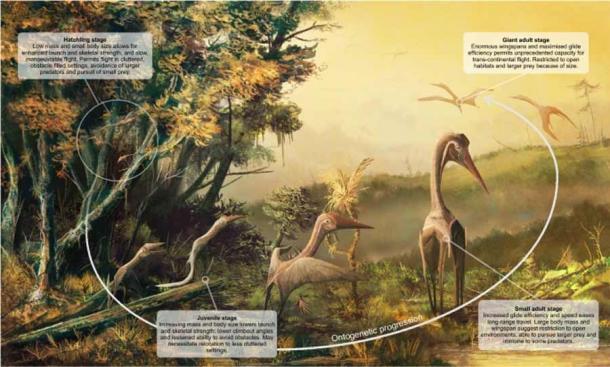

Visual summary of how basic, size-dependent flight parameters (wing loading, wingspan and aspect ratio) could have influenced pterosaur ecology throughout ontogeny. The animals shown here are giant azhdarchids, a species which likely had the largest ontogenetic mass differentials of any pterosaurs and thus potentially the broadest ecological range across their various growth stages. (Scientific Reports)

Rare Pterosaur Fossil Finds Reveal their Secrets Slowly

The new study represents a breakthrough, in an area of research that had been inhibited by a lack of fossil specimens to study. It is hard enough to find the fossilized bones of fully-grown dinosaurs, and even more difficult to recover fossils from tiny baby flying reptiles that lived tens of millions or hundreds of millions of years ago. Pterosaurs ruled the skies during the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods, spanning a length of time from 228 to 66 million years ago.

“Although we’ve known about pterosaurs for over two centuries, we’ve only had fossils of their embryos and hatchlings since 2004,” study co-author Dr. Mark Witton explained in a University of Portsmouth press release. “We’re still trying to understand the early stages of life in these animals.”

“We found that these tiny animals – with 25 cm wingspans and bodies that could neatly fit in your hand – were very strong, capable fliers,” he continued, discussing the latest study results. “Their bones were strong enough to sustain flapping and take-off, and their wings were ideally shaped for powered (as opposed to gliding) flight.”

Witton points out, however, that the flight performance of hatchling pterosaurs would have been quite different from that of their parents. Baby pterosaurs were literally hundreds of times smaller than adult versions, which would have made the babies much slower (but much more agile) fliers. As they grew rapidly their abilities would have evolved quickly. But even as babies they would have been able to get around easily and find enough food to survive.

Fossil imprint of Rhamphorhynchus, a flying pterosaur from the Jurassic period. (Wollwerth Imagery / Adobe Stock)

Unraveling Mysteries from an Impossibly Distant Past

University of Bristol researcher and study co-author Dr. Liz Martin-Silverstone stressed the importance of her team’s research methodology.

“There have been several debates about whether juvenile pterosaurs could fly,” she explained, “but this is the first time it’s been studied through a more biomechanical point of view. It’s exciting to discover that even though their wings may have been small, they were built in a way that made them strong enough to fly.”

In comparison to their gigantic parents swooping down from the heavens, baby pterosaurs flitting about wouldn’t have generated the same level of fear in their prey. Nevertheless, their small size and maneuverability would have given them certain advantages the larger versions wouldn’t have enjoyed. They would have been much better at tracking small prey through areas of dense vegetation, flying efficiently among and around trees to prevent their food from escaping.

Research into pterosaur capabilities, among youngsters and adults alike, is ongoing. With a limited number of fossils available to look at (for now), the science in this area may continue to progress slowly.

The new analysis does represent a major step forward, however.

“That gives us a lot to think about with regard to flying reptile ecology,” Dr. Witton said. “How independent were the hatchlings from their parents? Did flight style influence habitat choices, and did these change as pterosaurs grew? There’s still a lot to learn about the life histories of these animals. But we’re confident that, whatever they were doing as they grew up, they were capable of flying from the moment they hatched.”