A balloon apron is suspended to defend London from air attacks. 1915.

Observation was an incredibly important role in aerial warfare in World War I. All major combatants used observation balloons to observe their enemies’ trench lines and troop movements.

These hovering mammoths were used for directing artillery, which required spotters and observation well beyond the visual range of ground-based observers.

As much as planes were able to record enemy positions and movement on film, having real time spotters and observational balloon baskets linked to the ground by telephone was essential. It allowed the artillery to take advantage of increasingly large guns with vastly longer ranges.

The first military use of observation balloons was by the French Aerostatic Corps during the French Revolutionary Wars, the very first time during the Battle of Fleurus (1794).

The oldest preserved observation balloon, L’Intrépide, is on display in a Vienna museum. They were also used by both sides during the American Civil War (1861–65) and continued in use during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71).

World War I was the high point for the military use of observation balloons. The British, despite their experience in late 1800s Africa, were behind developments and were still using spherical balloons.

These were quickly replaced by more advanced types, known as kite balloons, which were aerodynamically shaped to be stable and could operate in more extreme weather conditions.

The Germans first developed the Parseval-Siegsfeld type balloon, and the French soon responded with the Caquot type.

French soldiers with cylinders of hydrogen used to inflate observation balloons. 1915.

Typically, balloons were tethered to a steel cable attached to a winch that reeled the gasbag to its desired height (often above 3,000 feet) and retrieved it at the end of an observation session.

Because of their importance as observation platforms, balloons were defended by anti-aircraft guns, groups of machine guns for low altitude defense, and patrolling fighter aircraft. Attacking a balloon was a risky venture but some pilots relished the challenge.

The most successful were known as balloon busters, including such notables as Belgium’s Willy Coppens, Germany’s Friedrich Ritter von Röth, America’s Frank Luke, and the Frenchmen Léon Bourjade, Michel Coiffard and Maurice Boyau.

Many expert balloon busters were careful not to go below 1,000 feet (300 m) in order to avoid exposure to anti-aircraft guns and machine guns.

The idiom “The balloon’s going up!” as an expression for impending battle is derived from the very fact that an observation balloon’s ascent likely signaled a preparatory bombardment for an offensive.

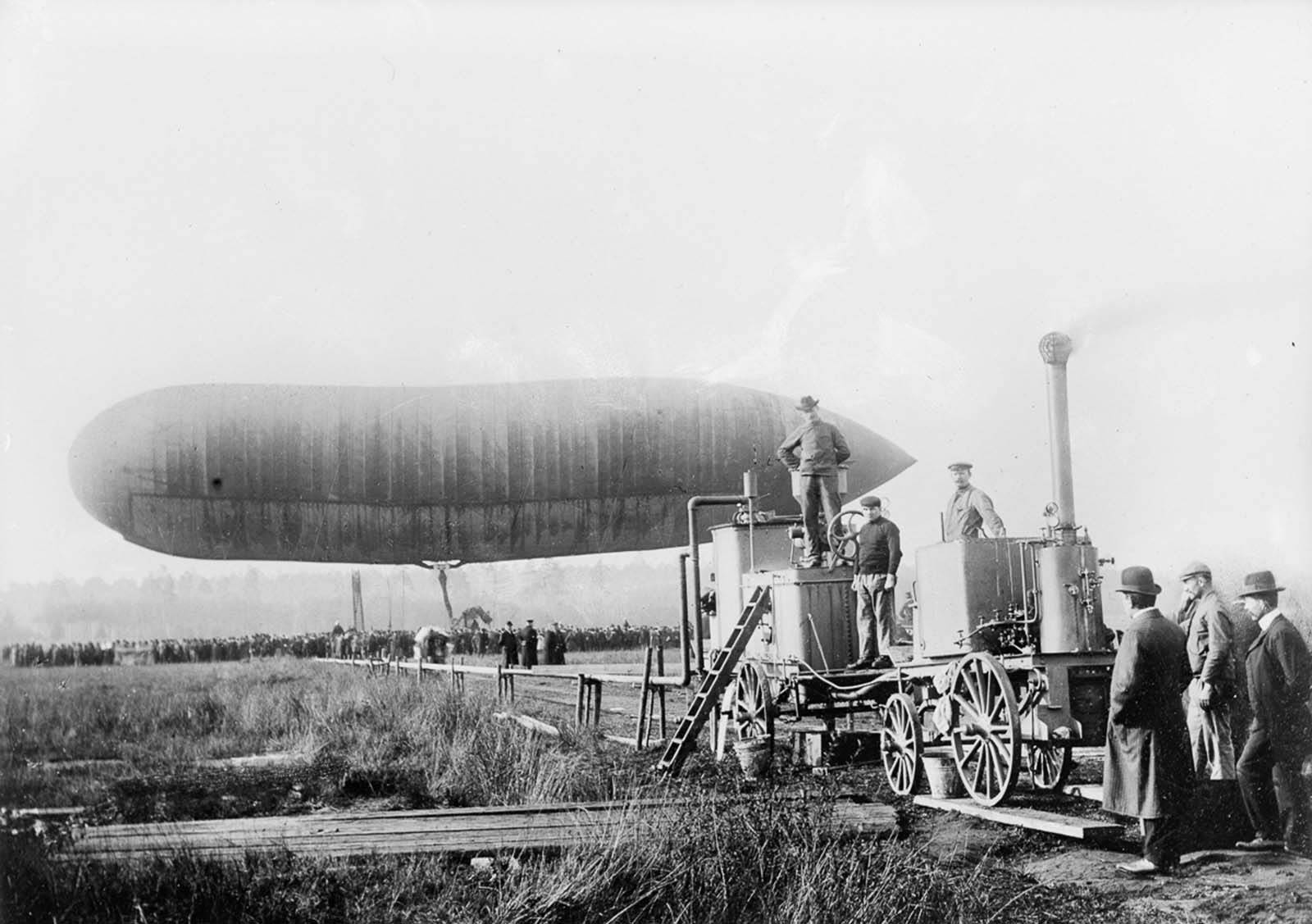

German soldiers generate power to inflate an observation balloon. 1914.

German soldiers inflate an observation balloon. 1915.

An Australian Royal Flying Corps balloon on the western front in Belgium. 1917.

A row of barrage balloons used for suspending aerial nets in Brindisi, Italy. 1918.

Australian soldiers watch an observation balloon ascend over Ypres, Belgium. 1917.

Hydrogen is pumped into an observation balloon to inflate it. 1914.

A German observation balloon fitted with a long-distance camera. 1916.

An observation balloon is inflated near Ypres, Belgium. 1917.

An observation balloon is launched near Ypres, Belgium to spot enemy artillery. 1917.

An observation balloon above the ruins of Ypres, Belgium. 1917.

An observation balloon is prepared for ascent in Ypres, Belgium. 1917.

An officer prepares to ascend in an observation balloon near the ruins of Ypres, Belgium. 1917.

A German observation balloon in flight. 1915.

An observation balloon ascends on the French front. 1915.

German soldiers help a high-altitude observer remove his heavy clothes. 1915.

A balloon burns on the ground after a German aerial attack. 1916.

A German observer leaps from his balloon with a parachute. 1916.

An observer is disentangled from a tree after parachuting from his balloon. 1918.