Deceiving the enemy as to what you are doing is not new. Trying to hide positions from observation is not new, trying to hide whole factories from aerial bombing during the Second World War was new.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese submarines were spotted off San Francisco Bay and near Santa Barbara in 1942.

The West Coast was the next presumed target for the Japanese so the U.S. decided to hide its major wartime factories.

In 1936, Boeing Plant 2 was finished with a goal to build early prototypes of the B-17 Flying Fortress and the Boeing 307 Stratoliners.

At this time the floor was 60,000 square feet (5,600 m2). 600,000 square feet (56,000 m2) was added to the plant in May 1940 to support Boeing production of 380 Douglas DB-7 light bombers.

By the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the plant had been expanded to 1,776,000 square feet (165,000 m2). In total, 6,981 B-17s were produced in Plant 2.

On the roof of Boeing Plant 2, camouflage trees and structures were shorter than 6 feet.

John Stewart Detlie was the Hollywood set designer who helped to hide Boeing Plant No. 2. Using the same techniques as in movie towns, fake streets, sidewalks, trees, fences, cars, and houses were set in place to fool the would-be attackers.

The idea was to blend the facility into the surrounding neighborhood across the river. This elaborate pretend town was nicknamed the “Boeing Wonderland” by the Seattle Daily Times on July 23, 1945.

Above, it could be mistaken for an idyllic residential area, so much so that it arguably looked a bit out of sync with its industrial surroundings.

Below, 30,000 men and women labored away, constructing 300 bombers per month to support the international war effort.

The disguises consisted of painting what appeared to be streets and greenery on real runways, and erecting entire faux subdivisions on factory rooftops.

The disguises consisted of painting what appeared to be streets and greenery on real runways, and erecting entire faux subdivisions on factory rooftops.

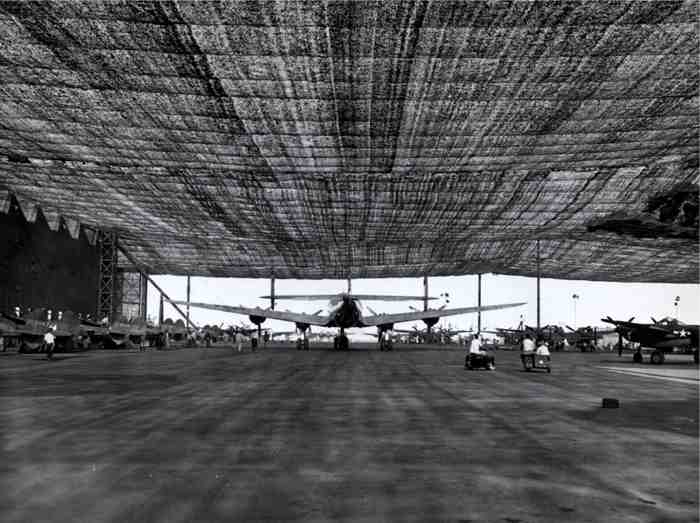

Standard-issue camouflage netting, stretched on massive wooden scaffolding served as the basic canvas on which the Hollywood artists painted contrasting color detailing to suggest streets and other features.

The netting was foliage green to begin with, but areas were sprayed in subtly different shades to give the scene a more realistic look. Some “lawns” in the subdivisions were painted brown to suggest that they had not been watered.

Dozens of fake houses, as well as schools and public buildings, were made of canvas. Hundreds of artificial shrubs and other ground details were created, using burlap over chicken wire matrices.

Suzette Lamoureaux and Vern Manion examine one of the miniature bungalows in the “Boeing Wonderland”

The movie industry illusionists developed a method of crafting trees using tar and feathers. Chicken wire was lightly coated with tar, and then dipped in chicken feathers.

The finished product, which had a soft, leafy appearance, could be formed into a rigid structure of any shape and sprayed multiple shades of green.

Chimneys and vents in the roofs of the factory buildings were allowed to poke through the netting, and were painted to simulate fireplugs.

Employees continued to do their work, encouraged by the placement of new bomb shelters and huge anti-aircraft guns, but were expected to play along with the illusion during their breaks, often walking back to their burlap bungalows to take down the laundry they had placed on clotheslines earlier in the day.

Structures that look like cars from overhead are parked along a fake street.

The fake houses and trees were not very tall; indeed, most of the buildings were no taller than six feet.

The reason was that the camouflage was designed to be seen from high above, not from ground level, and to be studied in minute detail only in the form of two-dimensional aerial photographs.

In practice, a bombardier would have no more than two minutes, if that, to view the target, and he would be looking straight down.

A street sign plays off the fake neighborhood at the corner of “Synthetic Street” and “Burlap Boulevard”.

By the time production ceased in the building, the plant had built half of the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses, the Boeing 307 Stratoliners, the Boeing 377s, some of the Boeing B-29 Superfortresses, Boeing B-50 Superfortresses, B-47 Stratojets, B-52 Stratofortresses, and the initial Boeing 737s.

In the 1980s, the plant was used as a machine shop but that was discontinued as work shifted to more modern facilities. The National Air and Space Museum’s Boeing 367-80 and the museum’s Boeing 307 were restored in the facility in 1990-2002.

All remaining aircraft were removed from Plant 2 on September 18, 2010. Eventually the main building fell into decay due to lack of adequate maintenance and earthquakes.

Broken water mains sometimes flooded the tunnels which led to other buildings on the site. Demolition began in late 2010.

Satellite buildings remain operational and on the footprint of the old plant are large tarmac lots for automobiles and airplanes.

Under an agreement with both state and federal governments as well as local Native American tribes, the company restored more than five acres of wetlands along the Duwamish River.

Trees were made of chicken wire and feathers.

An aerial view of the camouflage on top of Boeing Plant 2 shows that the “streets” were aligned with real residential neighborhoods nearby.

Joyce Howe, and behind her Susan Heidreich, walking over the camouflaged Boeing Plant 2.

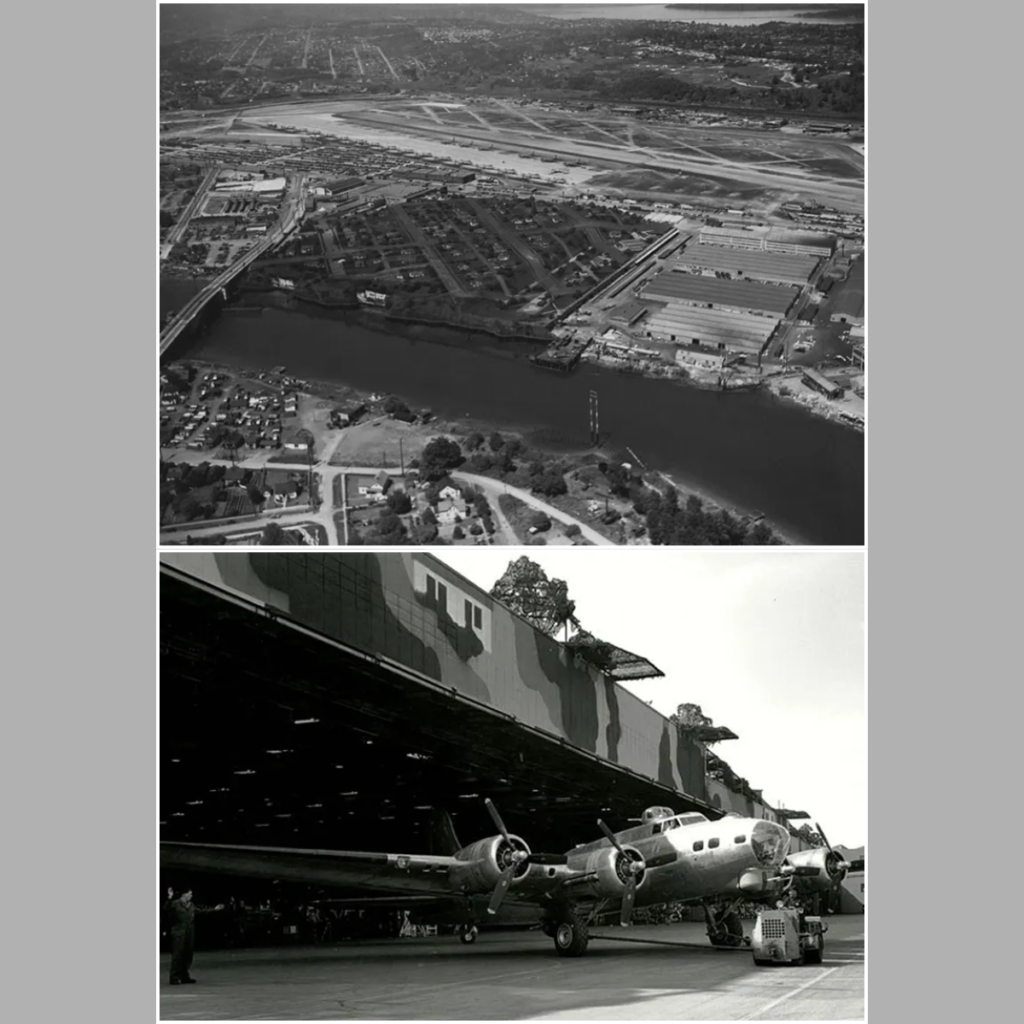

Aerial view of Boeing Plant 2 in Seattle, Washington, circa 1945.

The factory before the camouflage.

Aerial photo of Boeing Plant 2 dated 14 June, 1940.

Thousands of Boeing workers gather in front of Boeing Plant 2 for ceremonies marking the changeover from B-17 to B-29 production on April 10, 1945.

Boeing plant aerial photo taken from around 5000 feet.

Boeing Plant 2 “5000th plane” celebrations.

B-17F production line, Boeing Plant 2, July 1942.

“Rosie the Riveter” at work at Boeing Plant 2.

The first B-52A is rolled out at Boeing’s Seattle plant on March 18, 1954. In order to clear the hangar doorway, the plane’s 48-foot-high tail had to be folded down.