A multi-year series of excavations at a site near Lake Victoria in Kenya unearthed a collection of Oldowan stone tools that are likely the oldest ever found on Earth, dating back to the Pliocene epoch (between 5.3 and 2.5 million years ago). According to the American and British researchers involved in the latest study of the recovered artifacts, these tools (estimated to be a bit under 3 million years old) would have been used to butcher deceased hippos and pound edible plant material into a more appetizing shape.

Who, exactly, was doing the butchering and the pounding?

Past studies of Oldowan artifacts, which represented a huge leap forward in toolmaking technology, have credited their creation and use to the forerunners of modern humans. But the scientists found no fossilized remnants of human ancestors at the site in Kenya. What they discovered instead were two huge molars that belonged to an extinct ape-like creature known as Paranthropus. This hominin was distantly related to ancient humans, but its three different varieties ( Paranthropus aethiopicus, boisei and robustus) comprise a unique and separate genus, completely distinct from the Homo genus that includes modern humans and our ancestors.

Nyayanga site being excavated in July 2016. (J.S. Oliver/ Homa Peninsula Paleoanthropology Project)

The Oldowan tool collection and the fossilized molars found surprisingly close to it were uncovered during excavations at Nyayanga, a Pliocene site on the Homa Peninsula in western Kenya. In a study just published in the journal Science, the team responsible for this discovery, which included researchers from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Queens College in New York, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Liverpool John Moors University in the UK, and the National Museums of Kenya, discussed the possibility that Paranthropus might have been the toolmaker.

“The assumption among researchers has long been that only the genus Homo, to which humans belong, was capable of making stone tools,” said Smithsonian anthropologist and study senior author Rick Potts in a Smithsonian Institute press release. “But finding Paranthropus alongside these stone tools opens up a fascinating whodunnit.”

This is an historic discovery, as the Oldowan toolkit is currently believed to be the oldest example of its type ever found. The Paranthropus molars are also the oldest fossils of this species that have ever been recovered, and the fact that each discovery came from the same excavation site is quite remarkable. And if Paranthropus actually made the Oldowan tools, that would upend everything scientists thought they knew about how this toolkit first appeared on the earth.

Forensic reconstruction of a Paranthropus boisei. (Cicero Moraes/CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Oldowan Toolkit: A Revolutionary Historical Development

Until this recent find, the oldest known examples of Oldowan stone tools came from sites in Ethiopia’s Afar Triangle. These tools were dated to approximately 2.6 million years ago, as opposed to the tools found in Kenya that have tentatively been dated to 2.9 million years ago.

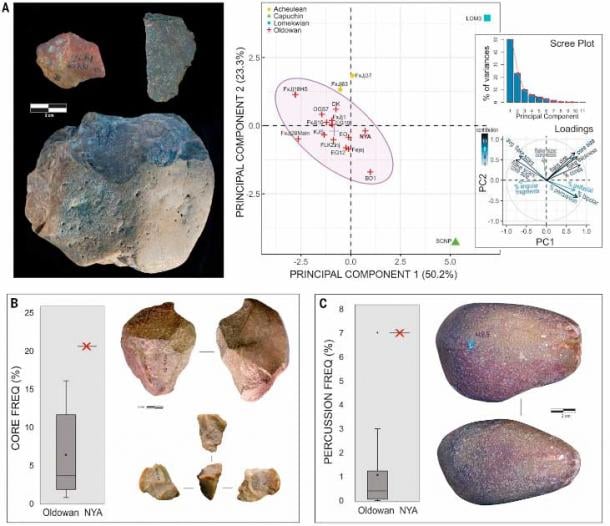

Representing the first true refinement of the original crude stone tools used by ancient hominins, the Oldowan kit included three types of specialized tools: hammerstones, cores and flakes.

As the name implies, hammerstones were used for pounding. They would have been useful for smashing rough plant material into something softer and more edible, and could also have been used to break rocks to make other tools.

Hammerstones were sometimes used in conjunction with cores, which were the earliest form of chisel. When a hammerstone and core were used together to chip away at a large rock, the sharp, flat pieces that broke off were known as flakes, and these could be used as scrapers or cutting knives.

“The appearance of Oldowan tools around 2.6 million years ago was a technological breakthrough that used systematically produced, sharp-edged flakes for cutting and cobbles or cores for percussion,” the study authors explained in their Science article.

An Oldowan toolkit was versatile enough to be used for a broad variety of activities. By analyzing the wear patterns on the stone tools and some animal bones found at Nyayanga, the scientists determined that the tools had been used to butcher animals and harvest and process plants for food and clothing.

Oldowan artifact technological analysis. (Plummer et al. /Science)

Regardless of what the tools were used for, they would have made life easier for Paranthropus just as they made it easier for humans—assuming, for the moment, that Paranthropus really did make the cache of Oldowan tools unearthed in Kenya.

“With these tools you can crush better than an elephant’s molar can and cut better than a lion’s canine can,” Potts said. “Oldowan technology was like suddenly evolving a brand-new set of teeth outside your body, and it opened up a new variety of foods on the African savannah to our ancestors.”

Did Paranthropus Really Make the Tools Found in Kenya?

Excavations began at Nyayanga in 2015, and up to now they have yielded more than 300 artifacts (tools), more than 1,700 animal bones and the two Paranthropus molars.

Among the animal bones were the remains of at least three hippos, and marks on the bones showed they had been butchered using Oldowan tools. These animals wouldn’t have been hunted, rather their bodies would have been scavenged after they’d died from some other cause. Since fire had not yet been harnessed and controlled, their meat would have been eaten raw.

Relying on various dating techniques, the researchers estimate the site could be anywhere from 2.58 to three million years old, although the bulk of the evidence suggests something closer to the latter number.

“This shows the toolkit was more widely distributed at an earlier date than people realized, and that it was used to process a wide variety of plant and animal tissues,” said study lead author Thomas Plummer, a Queens College anthropologist and research associate in the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program. “We don’t know for sure what the adaptive significance was, but the variety of uses suggests it was important to these hominins.”

While the discovery of the Paranthropus teeth would seem to indicate this genus made the tools, there could be another explanation.

Because Paranthropus was more ape-like than the ancestors of modern humans, the latter might have hunted the former and consumed its meat. This would mean the molars were remains left behind by human hunters. It’s also possible that ancient humans saw Paranthropus as their equals and had friendly relations with them, and that tools and other items were exchanged between the various hominin species that lived in eastern and southern Africa during the Pliocene epoch. This type of cooperation would have improved the odds of survival in a harsh and challenging environment.

“East Africa wasn’t a stable cradle for our species’ ancestors,” Rick Potts explained. “It was more of a boiling cauldron of environmental change, with downpours and droughts and a diverse, ever-changing menu of foods. Oldowan stone tools could have cut and pounded through it all and helped early toolmakers adapt to new places and new opportunities, whether it’s a dead hippo or a starchy root.”