Since this startling creature’s discovery in the 1970s, scientists were baffled as to how Quetzalcoatlus managed to get off the ground — but now they’ve finally solved the mystery.

The Quetzalcoatlus has baffled experts for decades. Part of the ancient pterosaur group of flying reptiles, its fossilized remains were first discovered in the 1970s and revealed a staggering wingspan of 40 feet. Although it was evidently the largest flying dinosaur that ever lived, exactly how it managed to fly remained a mystery — until now.

However, with its paper-thin bones, only a few dozen fossils stood the test of time. With each one safely kept at the University of Texas at Austin, researchers successfully renewed their efforts to find out how it flew.

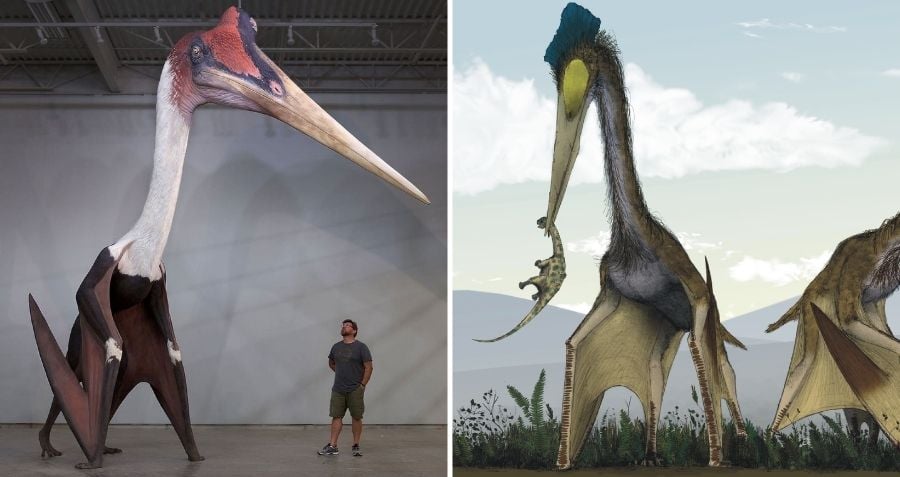

James KuetherQuetzalcoatlus stood 12 feet tall and weighed up to 500 pounds.

Older theories indicated the colossal creature rocked forward like a bat to take off or built up speed by running like an albatross. However, a new study published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology found that it leapt eight feet in the air to flap its wings, instead — shedding new light on an ancient enigma.

The Discovery Of Quetzalcoatlus, The Largest Flying Dinosaur Of All Time

Formally known as Quetzalcoatlus northropi, the winged creature is a member of the Azhdarchidae family of toothless pterosaurs with elongated necks. And although it stalked the continent during the Late Cretaceous period about 70 million years ago, its fossils were only first discovered in 1971.

Douglas Lawson had been a geology graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin when he discovered the first bone at Big Bend National Park in Brewster County, Texas. He named the genus after the feathered Quetzalcoatl serpent god from Aztec myth — and the species northropi after aircraft pioneer John Northrop.

According to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, the wingspan of Quetzalcoatlus northropi was 40 feet, about the same as an average city bus. Like other pterosaurs, its bones were found to be hollow to allow for flight.

Chicago Field MuseumA Quetzalcoatlus northropi display in the Chicago Field Museum.

But researchers also estimated that Quetzalcoatlus stood 12 feet tall and weighed up to 500 pounds, making it the largest flying dinosaur ever to live — if it could actually fly. Some scientists didn’t even believe that it would be capable of flying with so much mass.

Every Quetzalcoatlus fossil that exists was unearthed from Big Bend National Park. While there has been a frustrating scarcity, these remnants have all been safely secured at Lawson’s alma mater. But excavations have been slow going.

“You have these sort of potato chip-like bones preserved in very hard rock, and you’ve got to remove the bones from the rock without destroying them,” explained Matthew Brown, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Texas at Austin.

And this year, a new generation of researchers reviewed the fossils in a monograph of five papers that purports to show definitively that Quetzalcoatlus flew — and exactly how it managed to do so.

While Quetzalcoatlus was not a dinosaur per se, Quetzalcoatlus‘ existence alongside them has fascinated Kevin Padian for years. A co-author of one of the five papers and a paleontologist at the University of California, Berkeley, he believes this research sheds new light on pterosaurs — the first animals after insects to evolve flight.

“This ancient flying reptile is legendary, although most of the public conception of the animal is artistic, not scientific,” he said. “This is the first real look at the entirety of the largest animal ever to fly, as far as we know. The results are revolutionary for the study of pterosaurs.”

How Quetzalcoatlus Managed To Get Off The Ground Despite Its Enormous Size

The newly-released monograph covers a wide array of topics. These included the animal’s initial discovery and known distribution, their prehistoric habitat, physical characteristics, and taxonomy, as well as an updated evolutionary family tree and analysis of their morphology.

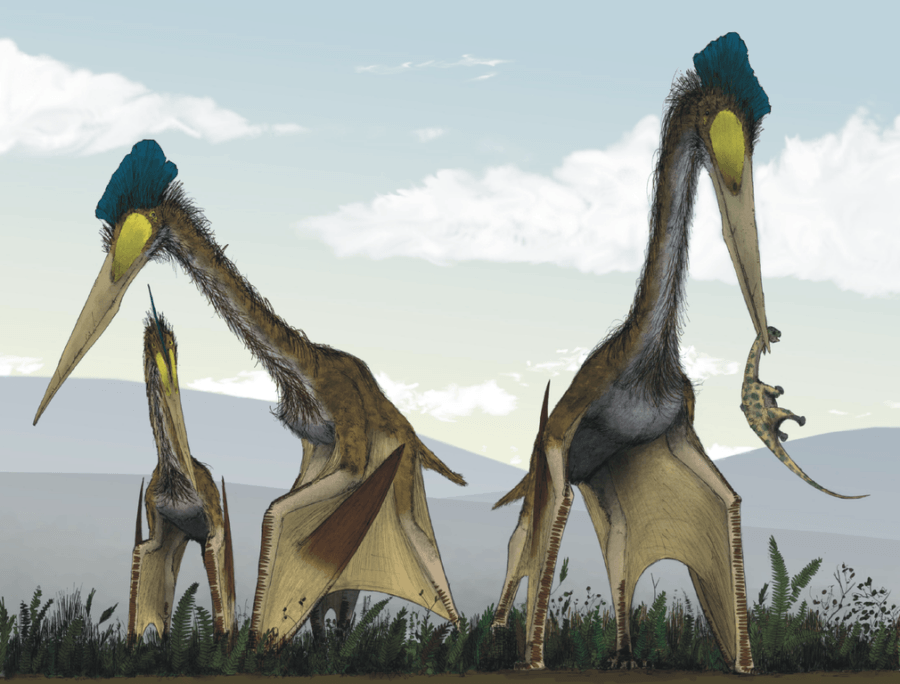

Mark P. Witton and Darren Naish/PLOS One via Wikimedia CommonsNew research indicates that despite their enormous size, Quetzalcoatlus northropi could fly by launching themselves into the air and flapping their wings.

“Pterosaurs have huge breastbones, which is where the flight muscles attach, so there is no doubt that they were terrific flyers,” said Padian.

Despite the range in size from large to small, researchers had attributed all previously uncovered fossils of Quetzalcoatlus northropi to that same species. It was only now that they realized that the smaller bones weren’t those of juvenile members, but belonged to two previously unknown pterosaur species, instead.

“To say that this work is long awaited is something of an understatement,” said pterosaur expert Darren Naish.

Identified as Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni, one of them was named in honor of Douglas Lawson and was only the second Quetzalcoatlus to ever be found. This creature had a wingspan between 18 and 20 feet. The other pterosaur species was christened Wellnhopterus brevirostri and is unrelated to Quetzalcoatlus.

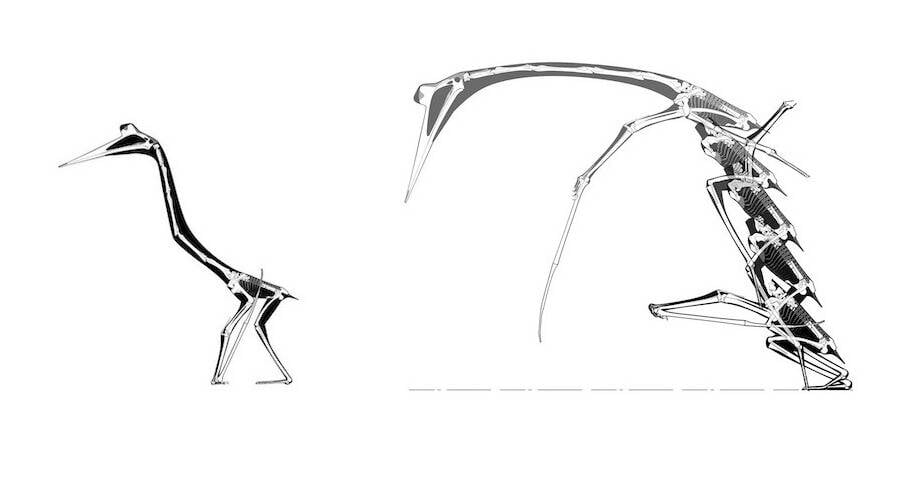

In order to determine how Quetzalcoatlus northropi became the largest flying dinosaur, researchers partially reconstructed the bones of its smaller species in order to find out more. Scientists discovered that the flying reptile did not rock back and forth like a bat. Nor did it gather speed by running like an albatross as had previously been theorized.

Journal of Vertebrate PaleontologyA Quetzalcoatlus standing in place (left) and a step-by-step reconstruction of its potential launch into flight (right).

Instead, Quetzalcoatlus jumped eight feet straight up into the air and started flapping its giant wings before soaring away.

“We applied a lot of the aerospace knowledge to understanding how something like airfoil works and how much speed you need to generate lift,” said Brown.

The work also revealed larger Quetzalcoatlus lived like herons, hunting alone in rivers and streams. Then an evergreen forest, Big Bend provided a plethora of crabs, clams, and worms for them to eat with their long and toothless beaks. Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni were more social — their bones found together in one place.

“The good news is that it very much delivers…[as never] before has so much detailed information on azhdarchids been gathered in the same place, this meaning that the work will serve as the standard go-to study of this group for years — probably decades — to come,” said Naish.