An international team of scientists have revealed secrets about the ancient creation skills, trade and economy of decorated ostrich eggs in the Mediterranean and Middle East.

Easter is here again and while for many the holiday (holy-day) marks the resurrection of Christ, others use the date as permission to indulge in their favorite, oh so wonderful, chocolate eggs. But this Easter brings a special scientific treat in the form of a new paper revealing the complexity of the production and trade systems associated with luxury decorated ostrich eggs during the Bronze and Iron Ages across the Mediterranean and Middle East.

Unscrambling Ostrich Eggs in History

A team of archaeologists from the Universities of Bristol and Durham in England are spearheaded by Tamar Hodos, a senior lecturer in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Bristol and author of the 2006 book Local Responses to Colonization in the Iron Age Mediterranean. In their new paper, published in the journal Antiquity, the researchers say during the Bronze and Iron Ages, “decorated ostrich eggs” were traded around the Mediterranean, and they present new observations pertaining to the production techniques, iconography and trade networks, attempting to categorize individual producers, workshops and trade routes.

Map of Middle Eastern/Mediterranean study area. (Tamar Hodos et al. / Antiquity Publications Ltd)

The overall aim of this multidisciplinary science project was to equate unique decorative styles with different cultural identities from various geographic locations and according to the lead author, Tamar Hodos, achieving this was “problematic, as craftspeople were mobile and worked in the service of foreign royal patrons.”

Shell Iconography is a Thin Data Layer Compared to What Lies Within

In ancient times all across Mesopotamia and the greater Levant, engraved and painted ostrich eggs were decorated with ivory, bronze, silver and gold and traded as exotic luxury items and status markers in the Bronze Age (c. third to second millennia BC) and Iron Age (c. first millennium BC) when they were often buried with social elites.

What is more, Assyrian royal texts mention the exploitation of ostriches, for example in The Banquet Stele of King Assurnasirpal II (883–859 BC), he slays and traps numerous elephants, lions, wild bulls and “ostriches” for his palace pleasure gardens.

During the Bronze Age, ostriches were imported from the Middle East and/or North Africa and the question regarding who decorated these eggs has traditionally leaned on iconographic analysis, but this new study looked at five whole ostrich eggs in the British Museum collection that were found in the Isis Tomb: an elite burial at Etruscan Vulci (Italy) dated to c. 625–550 BC.

Two of the decorative ostrich eggs from the Isis tomb on show in the British Museum. (Tamar Hodos et al. / Antiquity Publications Ltd)

Four are carved and painted and one is painted only with “animals, flora, geometric patterns, soldiers and chariots,” which according to the new paper were fashioned into vessels with metal attachments, none of which survived.

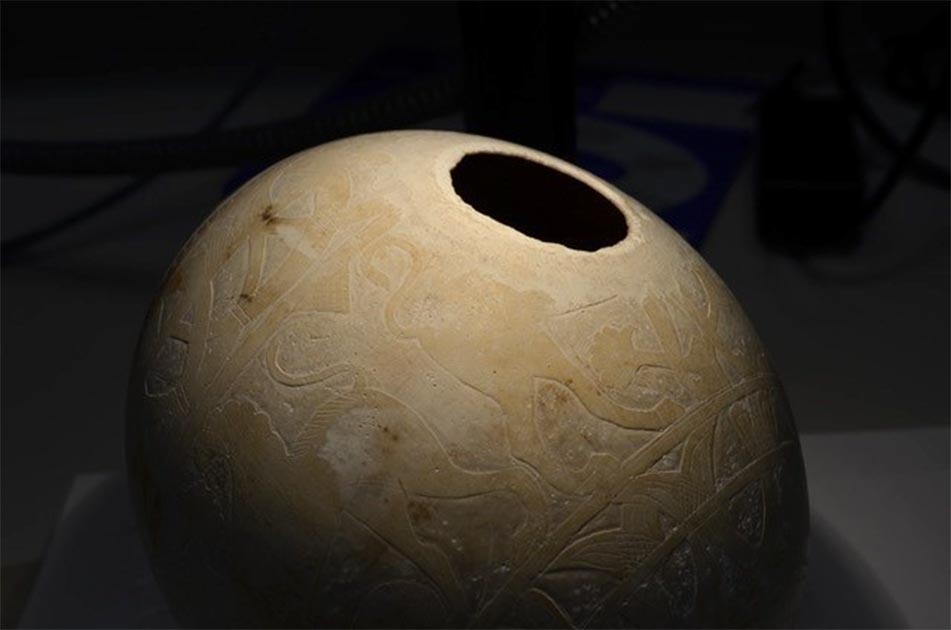

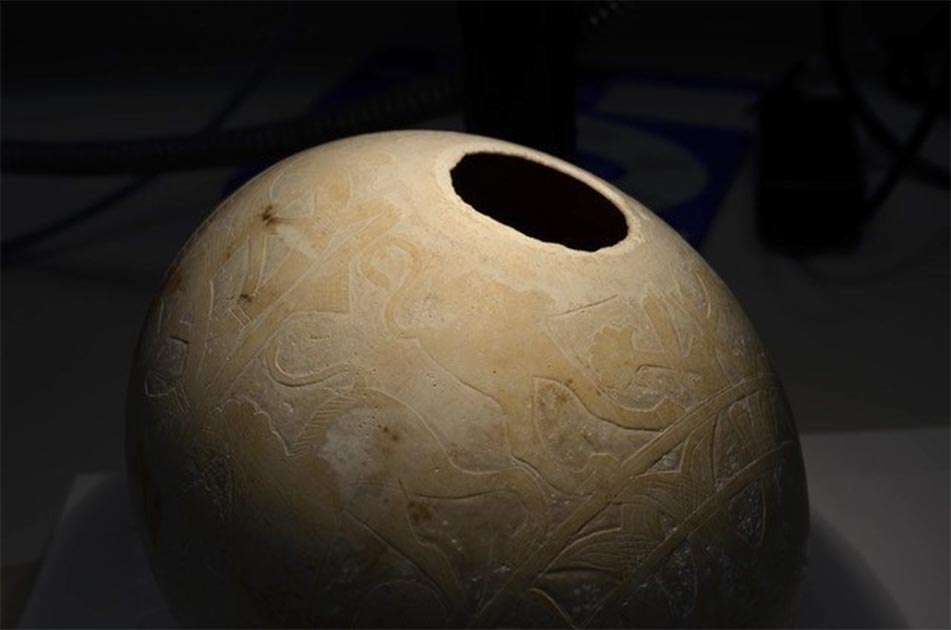

Close up of an ostrich egg that was used in the study and has been decorated with painted animal carvings. (Tamar Hodos et al. / Antiquity Publications Ltd)

Tracking the Shell Trails of Ancient Ostrich Eggs

These eggs’ motifs and working methods have been compared with contemporaneous Levantine and Mesopotamian ivory workings, but no Mediterranean egg carving sites have been identified to date for comparison.

To assess the eggs’ origins, the five samples from the British Museum were subjected to strontium, carbon and oxygen isotope analyses to establish whether their isotope ratios matched the region in which they were found, based on the ostriches’ diets, which contain markers pertaining to their geology and climate.

Close up of one of the ostrich eggs used in the study showing the decorative engravings and markings. (Tamar Hodos et al. / Antiquity Publications Ltd)

Ten further ancient decorated ostrich-eggshells were examined for tool marks and working techniques using a “Leica MZ APO optical microscope,” which determined that one egg (988) was laid in Amara West Sudan, which had a higher strontium isotope ratio, i.e. higher than seawater and other eggs excavated at the same site.

Whereas example (973) from Ur, Iraq, had the lowest ratio in comparison to other ostrich eggshells from Ur. These results suggest that these particular eggs were laid by birds living in different geological, and hence geographic environments to the other ostrich eggshells at the same site.

The results also indicate a fluctuation in egg sources between relatively local and more distant locations in both the Bronze and Iron Ages and this implies complex trade and exchange networks that were “more flexible, opportunistic and extensive than has been previously considered.”

Close up of an ostrich egg that was used in the study and has been carved and painted. (Tamar Hodos et al. / Antiquity Publications Ltd)

The researchers concluded that the eggs were obtained from the wild rather than through managed (farmed) means, but they said additional experimental work, more comparative data and further study of decorating techniques are necessary to investigate discernible patterns regarding egg decoration and potential nest sites.

Were Ostrich Eggs Representative of Resurrection?

The egg was an ancient symbol used across pagan traditions as a symbol of new life and it was associated spring festivals. But from a Christian perspective, “Easter eggs” are representative of Jesus’ emergence from the tomb and resurrection, but what did ostrich eggs represent in Mesopotamia?

In an email to the author of the new paper, Tamar Hodos, I asked her if the illustrations and decorations were also symbolic of death or rebirth? and she replied “for a number of cultures, an egg itself is symbolic of rebirth, but it is hard to answer your question simply for a few reasons. One is that the [ostrich] eggs are part of material culture over several thousand years, and material culture across different cultures, who have different beliefs, practices, etc.”

Dr. Tamar also pointed out a further complication in categorizing designed ostrich eggs informing “if a Phoenician artist is working in Assyria for an Assyrian king, then should we consider that egg to be Phoenician or Assyrian?” and it is this type of paradoxical question that drives Dr. Tamar’s whole style and approach.

What is perhaps most refreshing in this new paper is that Dr. Tamar and her teams are not afraid to admit that they “don’t have all the answers,” but what they certainly do have, are some fascinating questions, which are in themselves pulling together the scattered jigsaw of the broader cultural role of ostrich eggs in the ancient world.