As the 20th century approached, Native American communities faced mounting challenges to their existence and traditional ways of life.

As the 20th century approached, Native American communities faced mounting challenges to their existence and traditional ways of life.

After the Civil War, large numbers of white settlers moved westward, spurred on by the expansion of railroads. This migration reshaped the frontier, impacting the land and its inhabitants profoundly.

Settlers not only cultivated the land but also hunted American bison extensively. Native American tribes often found themselves outnumbered in conflicts with both settlers and the U.S. government.

By the 1880s, most Native Americans had been confined to reservations, often in remote areas. Many feared their traditional lifestyle was under threat of disappearing forever.

Meanwhile, pioneering photographers like Edward Curtis, Walter McClintock, and Herman Heyn worked to preserve Native American culture through photography.

These colored old photos offer a vivid glimpse into a changing world, which you can explore in this photo collection.

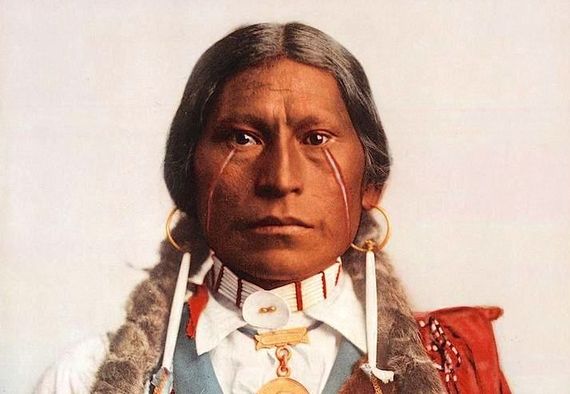

Bone Necklace. Oglala Lakota Chief. 1899. Photo by Heyn Photo.

Edward Curtis, a photographer from Seattle, felt a pressing need to document Native American culture, sensing time was running out. When he reached some reservations, however, he found he was too late.

Many Native American children were in boarding schools, forbidden from using their languages or practicing their cultures.

Nevertheless, Curtis persisted. He aimed to capture what he saw as a disappearing culture through his camera lens. During his lifetime, Curtis took over 40,000 pictures of Native Americans.

While he often focused on traditional aspects, encouraging his subjects to pose in ceremonial clothing, Curtis left behind a remarkable legacy of work.

But Curtis wasn’t the only photographer interested in preserving Native American culture. Walter McClintock, a Yale graduate, also traveled west to photograph this rich heritage.

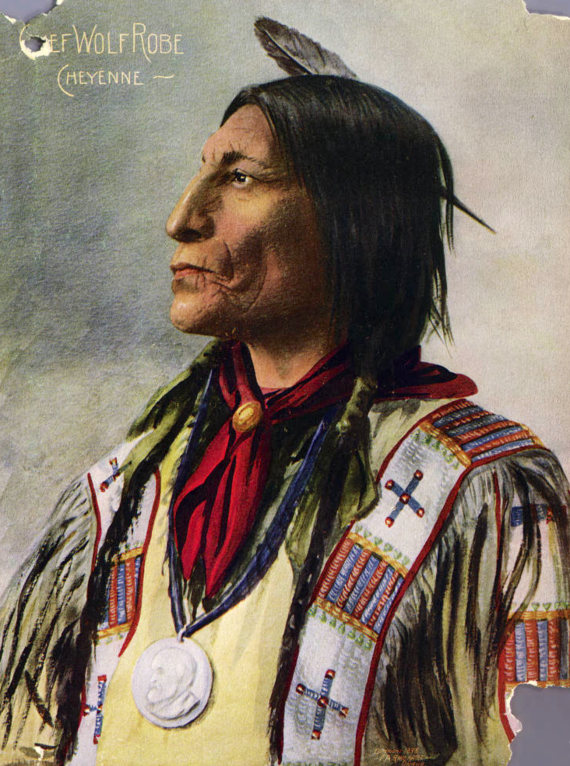

Cheyenne Chief Wolf Robe. Color halftone reproduction of a painting from a Rinehart photograph. 1898.

Like Curtis, McClintock believed in using photography to preserve a culture on the verge of disappearing.

He also focused on traditional aspects. McClintock took an extra step compared to Curtis by adding color to his photographs.

Between 1903 and 1912, McClintock took over 2,000 photographs of the Blackfoot people in Montana. He sent some of his negatives to a Chicago colorist named Charlotte Pinkerton.

Using McClintock’s notes, Pinkerton carefully added colors to his photographs, likely using techniques common during that time, such as applying pigments with oil, varnish, watercolor, or dyes.

McClintock displayed his colored photographs using a “magic lantern,” an early version of modern image projectors.

This device projected light through a glass sheet with an image, creating a larger picture to impress the audience.

Eagle Arrow. A Siksika man. Montana. Early 1900s. Glass lantern slide by Walter McClintock.

Chief Little Wound and family. Oglala Lakota. 1899. Photo by Heyn Photo.

Strong Left Hand and family. Northern Cheyenne Reservation. 1906. Photo by Julia Tuell.

Minnehaha. 1904. Photochrom print by the Detroit Photographic Co.

Amos Two Bulls. Lakota. Photo by Gertrude Käsebier. 1900.

A medicine man with patient. Taos Pueblo, New Mexico. 1905. Photo by Carl Moon.

A medicine man with patient. Taos Pueblo, New Mexico. 1905. Photo by Carl Moon.

Charles American Horse (the son of Chief American Horse). Oglala Lakota. 1901. Photo by William Herman Rau.

Acoma pueblo. New Mexico. Early 1900s. Photo by Chicago Transparency Company.

A Crow dancer. Early 1900s. Photo by Richard Throssel.

Thunder Tipi of Brings-Down-The-Sun. Blackfoot camp. Early 1900s. Glass lantern slide by Walter McClintock.

Handpainted print depicting five riders going downhill in Montana. Early 1900s. Photo by Roland W. Reed.

Handpainted print depicting five riders going downhill in Montana. Early 1900s. Photo by Roland W. Reed.

Piegan men giving prayer to the Thunderbird near a river in Montana. 1912. Photo by Roland W. Reed.

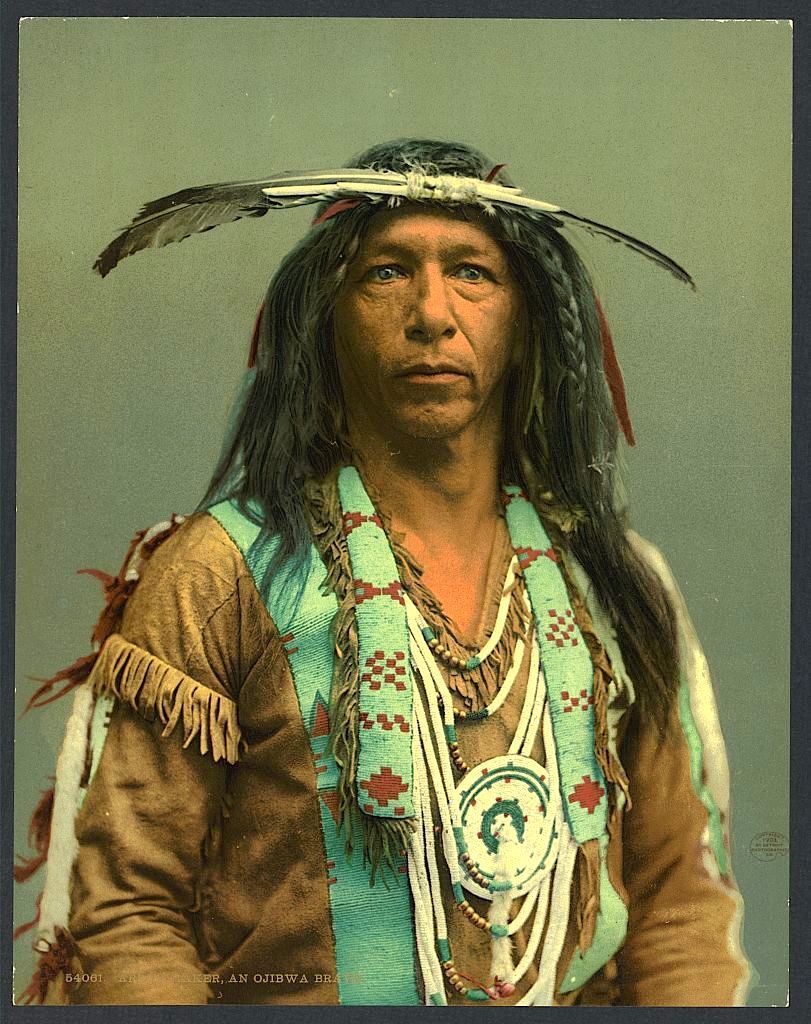

Arrowmaker, an Ojibwe man. 1903. Photochrom print by the Detroit Photographic Co.

Northern Plains man on an overlook. Montana. Early 1900s. Hand-colored photo by Roland W. Reed.

“Songlike”, a Pueblo man, 1899. Photo by F.A. Rinehart.

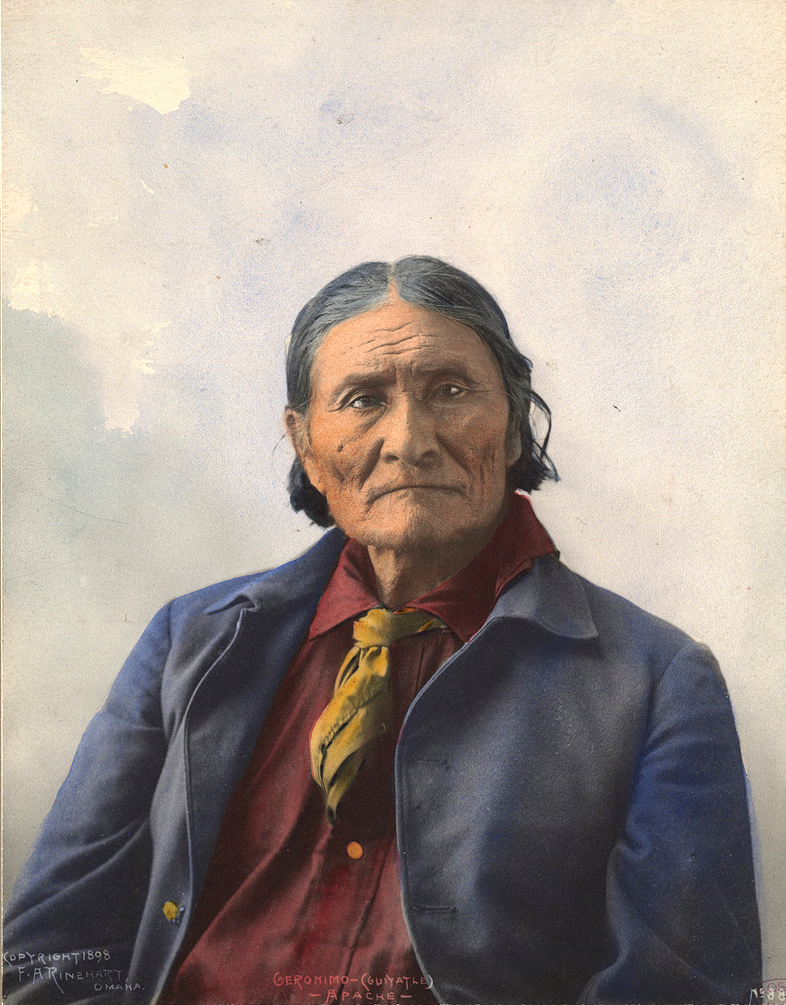

Geronimo (Goyaałé). Apache. 1898. Photo by F.A. Rinehart. Omaha, Nebraska.

Blackfeet tribal camp with grazing horses. Montana. Early 1900s. Glass lantern slide by Walter McClintock.

Handpainted print of a young woman by the river. Early 1900s. Photo by Roland W. Reed.

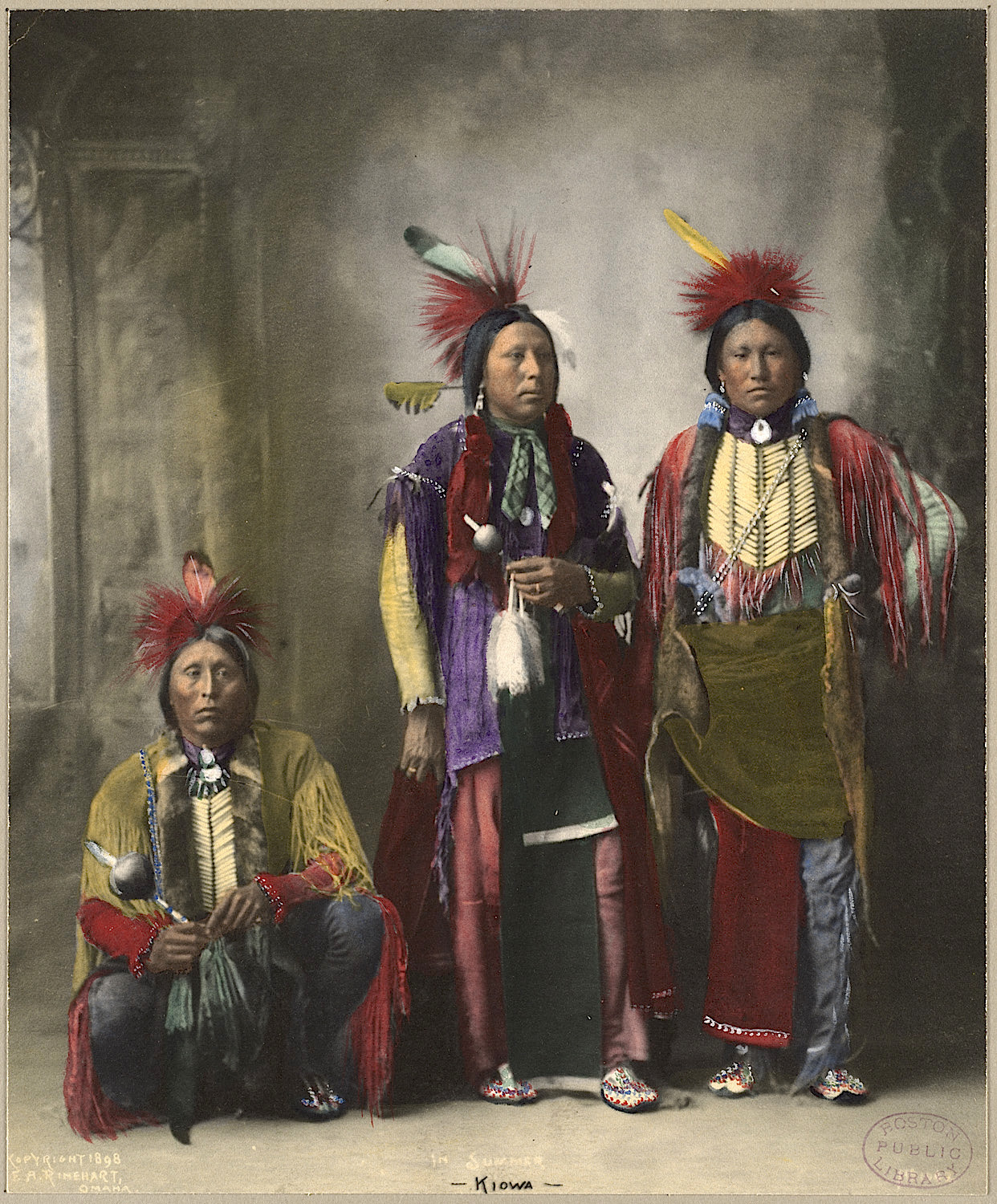

“In Summer”. Kiowa. 1898. Photo by F.A. Rinehart.

Blackfeet girl. Montana. Early 1900s.

Blackfeet group. Montana. Early 1900s.

In the snowy prairie. Blackfeet. Montana. Early 1900s.

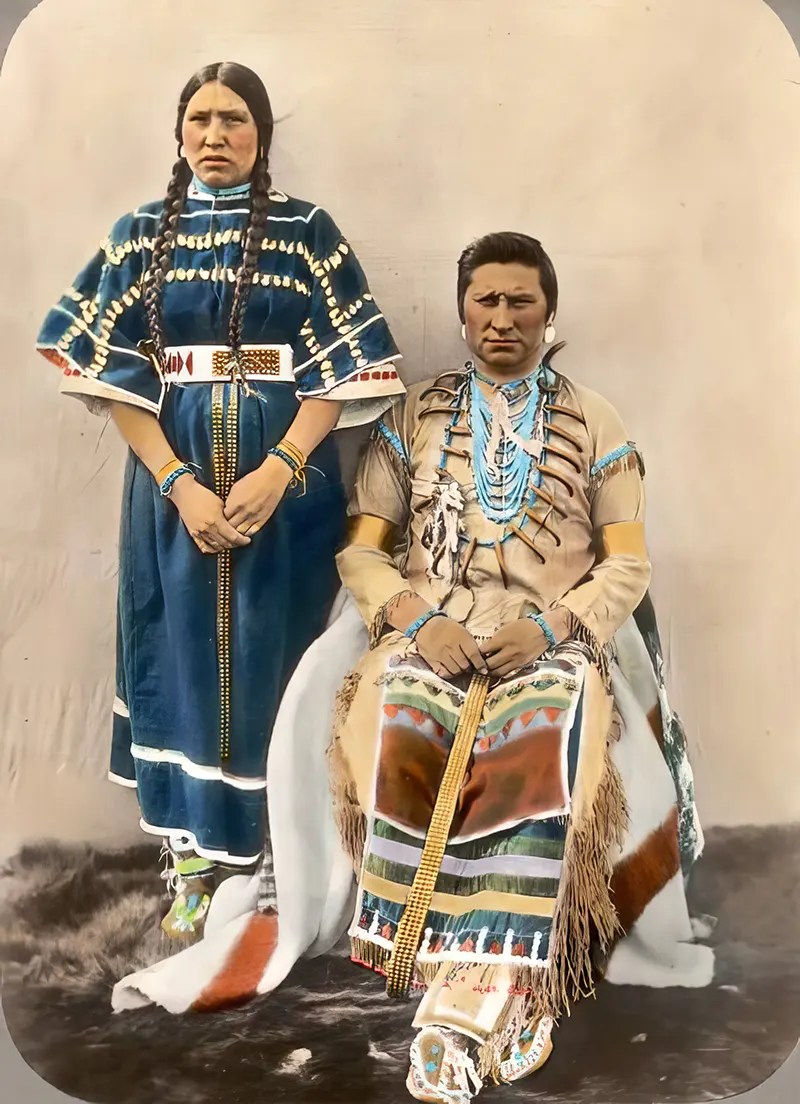

A Blackfoot couple. Montana. Early 1900s.

“Coming Running.” Blackfeet woman with children. Montana. Early 1900s.

Broken Arm (Isto Nawege). Oglala Lakota. 1898. Photo taken by Frank Rinehart.

Cayuse Twins (Tax-a-Lax and Alompum). Photo taken by Lee Moorhouse, an Indian agent for the Umatilla Indian Reservation, in 1898.

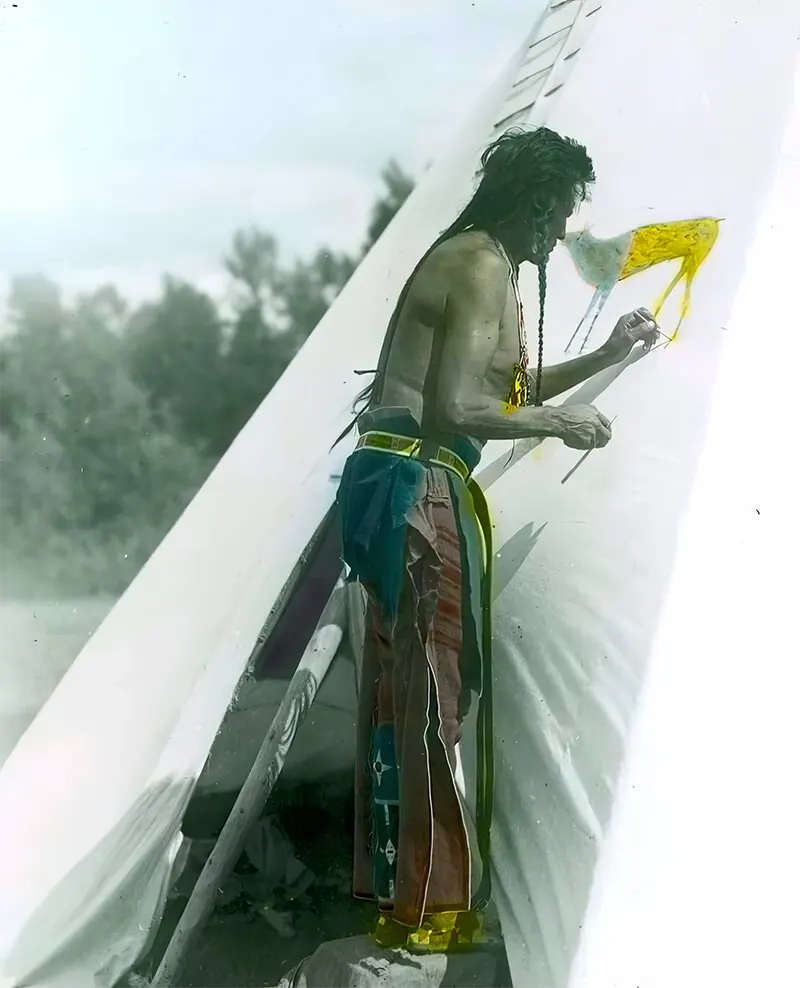

Painting the tipi possibly with “the sign of his medicine” as described by the photographer. Crow camp. Montana. Early 1900s.

A Siksika woman. Montana. Early 1900s.

Snake Whistle. Cheyenne. Fort Keogh, Montana. 1880.

Vapore. Maricopa man. 1899. Omaha, Nebraska.

Walks-In-The-Water (Soya-wa-awachkai) and her baby Koumiski (Round Face). Siksika. Montana. Early 1900s.

Woman chopping firewood, Eagle tipi in foreground, Star tipi on left. Blackfoot camp. Early 1900s.