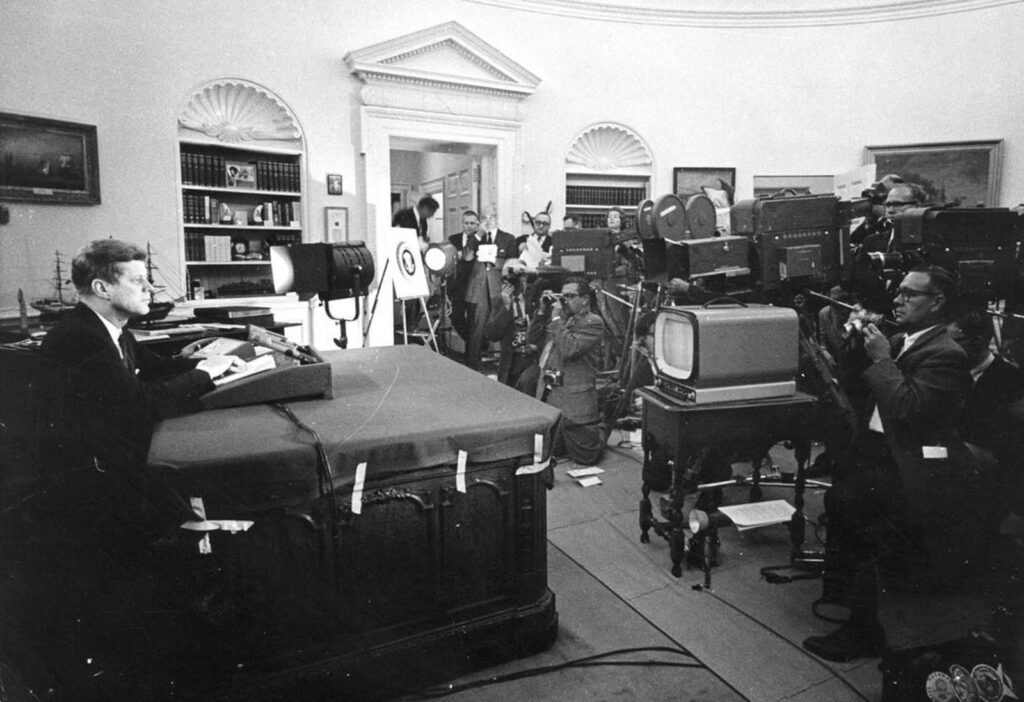

U.S. President John F. Kennedy speaks before reporters during a televised speech to the nation about the strategic blockade of Cuba, and his warning to the Soviet Union about missile sanctions, during the Cuban missile crisis, on October 24, 1962 in Washington, DC.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 was a direct and dangerous confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War and was the moment when the two superpowers came closest to nuclear conflict.

The crisis was unique in a number of ways, featuring calculations and miscalculations as well as direct and secret communications and miscommunications between the two sides.

The dramatic crisis was also characterized by the fact that it was primarily played out at the White House and the Kremlin level with relatively little input from the respective bureaucracies typically involved in the foreign policy process.

In October 1962 President John F. Kennedy was informed of a U-2 spy-plane’s discovery of Soviet nuclear-tipped missiles in Cuba. The President resolved immediately that this could not stand.

Over an intense 13 days, he and his Soviet counterpart Nikita Khrushchev confronted each other “eyeball to eyeball,” each with the power of mutual destruction. A war would have meant the deaths of 100 million Americans and more than 100 million Soviets.

A spy photo of a medium-range ballistic missile base in San Cristobal, Cuba, with labels detailing various parts of the base, displayed in October of 1962.

Pausing at the nuclear precipice, President Kennedy and the group of advisors he had assembled (known as ExComm) evaluated a number of options.

After a week of secret deliberations, he announced the discovery to the world and imposed a naval blockade on further shipments of armaments to Cuba.

A tense second week followed, during which neither side backed down. Presented with the choice of attacking or accepting Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba, Kennedy rejected both options.

Instead, he crafted an alternative with three components: a public deal in which the United States pledged not to invade Cuba if the Soviet Union withdrew its missiles; a private ultimatum threatening to attack Cuba within 24 hours if the offer was rejected; and a secret sweetener that promised to withdraw U.S. missiles from Turkey within six months. The crisis was resolved at the last minute when Khrushchev accepted the U.S. offer.

Evidence presented by the U.S. Department of Defense, of Soviet missiles in Cuba. This low-level photo, made October 23, 1962, of the medium-range ballistic missile site under construction at Cuba’s San Cristobal area. A line of oxidizer trailers is at center. Added since October 14, the site was earlier photographed, are fuel trailers, a missile shelter tent, and equipment. The missile erector now lies under canvas cover. Evident also are extensive vehicle tracks and the construction of cable lines to control areas.

The Cuban missile crisis stands as a singular event during the Cold War and strengthened Kennedy’s image domestically and internationally. It also may have helped mitigate negative world opinion regarding the failed Bay of Pigs invasion.

Two other important results of the crisis came in unique forms. First, despite the flurry of direct and indirect communications between the White House and the Kremlin—perhaps because of it—Kennedy and Khrushchev, and their advisers, struggled throughout the crisis to clearly understand each others’ true intentions, while the world hung on the brink of possible nuclear war.

In an effort to prevent this from happening again, a direct telephone link between the White House and the Kremlin was established; it became known as the “Hotline”.

Second, having approached the brink of nuclear conflict, both superpowers began to reconsider the nuclear arms race and took the first steps in agreeing to a nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

President John F. Kennedy meets with Air Force Maj. Richard Heyser, left, and Air Force Chief of Staff, Gen. Curtis LeMay, center, at the White House in Washington to discuss U-2 spy plane flights over Cuba.

A map of Cuba annotated by former U.S. President John F. Kennedy, displayed for the first time at the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts, on July 13, 2005. Former President Kennedy wrote “Missile Sites” on the map and marked them with an X when he was first briefed by the CIA on the Cuban Missile Crisis on October 16, 1962.

A photograph of a ballistic missile base in Cuba, used as evidence with which U.S. President John F. Kennedy ordered a naval blockade of Cuba during the Cuban missile crisis, on October 24, 1962.

President John F. Kennedy tells the American people that the U.S. is setting up a naval blockade against Cuba, during a television and radio address, on October 22, 1962, from the White House. The president also said the U.S. would wreak “a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union” if any nuclear missile is fired on any nation in this hemisphere”.

U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, Adlai Stevenson, second from right, confronts Soviet delegate Valerian Zorin, first on left, with a display of reconnaissance photographs during emergency session of the U.N. Security Council at the United Nations headquarters in New York, on October 25, 1962.

A composite image of three photographs taken on October 23, 1962, during a United Nations Security Council meeting on the Cuban Missile Crisis. From left, Soviet foreign deputy minister Valerian A. Zorin; Cuba’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Mario Garcia-Inchaustegui; and U.S. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson.

Cuban President Fidel Castro replies to President Kennedy’s naval blockade via Cuban radio and television, on October 23, 1962.

President John F. Kennedy signs a proclamation enacting the U.S. arms quarantine against Cuba, on October 23, 1962.

Picketers representing an organization known as Women Strike for Peace carry placards outside the United Nations headquarters in New York City, where the U.N. Security Council considers the Cuban missile crisis in a special meeting, on October 23, 1962.

Two soldiers sit in a sandy dugout beside a machine gun hold position on a beach on Key West, Florida, on October 27, 1962.

New Yorkers eager for news of the Cuban missile crisis line up to buy newspapers in October of 1962.

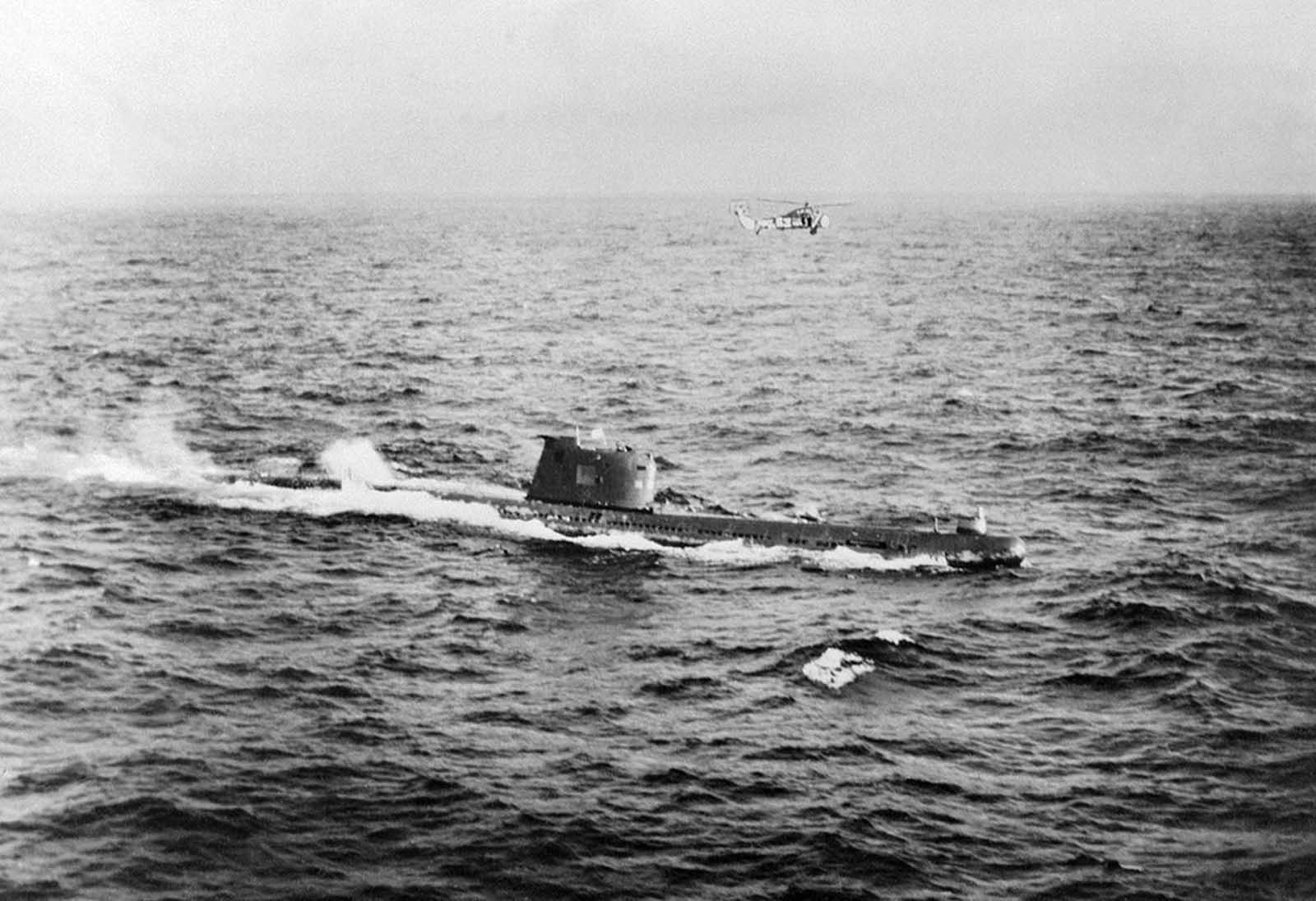

U.S. Navy surveillance of the first Soviet F-class submarine to surface near the Cuban quarantine line on October 25, 1962.

Members of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) march during a protest against the U.S. action over the Cuban missile crisis, on October 28, 1962 in London, England.

U.S. Army anti-aircraft rockets, mounted on launchers and pointed out over the Florida Straits in Key West, Florida, on October 27, 1962.

A low-level photograph taken November 1, 1962, of a Medium Range Ballistic Missile Site at Sagua La Grande, Cuba.

President John Kennedy reports personally to the nation on the status of the Cuban crisis, telling the American people that Soviet missile bases in Cuba are “being destroyed”, on November 2, 1962. He said U.S. air surveillance will continue until the effective international inspection is arranged.

Soviet personnel and six missile transporters loaded onto a Soviet ship in Cuba’s Casilda port, on November 6, 1962. Note shadow at the lower right of the RF-101 reconnaissance jet taking the photograph.

A P2V Neptune U.S. patrol plane flies over a Soviet freighter during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962.

The Soviet ship Kasimov removes 15 Soviet I1-28 aircraft from Cuba after the U.S. asked for their withdrawal.

A Soviet submarine near the Cuban coast controlling the operations of withdrawal of the Russian Missiles from Cuba in accordance with the US-Soviet agreement, on November 10, 1962. American planes and helicopters flew at a low level to keep close check on the dismantling and loading operations, while US warships watched over Soviet freighters carrying missiles back to the Soviet Union.

A group of U.S. Army hospital tents and ambulances, set up at the Opa Locka airport, formerly a marine air station in Miami, Florida in November of 1962.

Buildup of troops and military equipment, rushed to south Florida to launch an invasion of Cuba if it had been ordered, remained on the keys, between Miami and Key West. This unit, showing no sign of dismantling, was manned and ready with its anti-aircraft missiles in Key West on November 21, 1962.

The U.S. Navy guided-missile ship Dahlgren trails the Soviet Leninsky Komsomol as the Russian vessel departed Casilda, Cuba, on November 10, 1962.