Conventional wisdom says that ancient humans made the transition from walking on four legs to walking on two because they needed to travel more efficiently across open savanna land in Africa. But based on some stunning new findings just published in the journal Science Advances, it seems this conclusion may not be correct.

According to researchers affiliated with three prestigious universities in the United Kingdom and the United States, it is likely that early human ancestors first became bipedal while they were still moving about in the trees, side by side with other primate species.

Conclusions About Upright Walking Reached by Observing Chimpanzees

The research that led to this fascinating conclusion did not include a direct analysis of any paleontological, a.k.a. fossil, evidence. Instead, anthropologists from University College London, the University of Kent and Duke University in North Carolina spent 15 months observing the behavior of chimpanzees living in the Issa Valley of Tanzania.

Chimpanzees are humanity’s closest living primate relative. As such it is believed their actions and reactions can shed light on what ancient hominin ancestors of Homo sapiens, or modern humans, were doing millions of years ago.

In addition to the close genetic connection, these chimpanzees have something else in common with prehistoric humans. These animals live in an eco-region known as savanna-mosaic, an area that almost perfectly matches the environment in which the earliest humans evolved and developed the ability to walk upright on two legs.

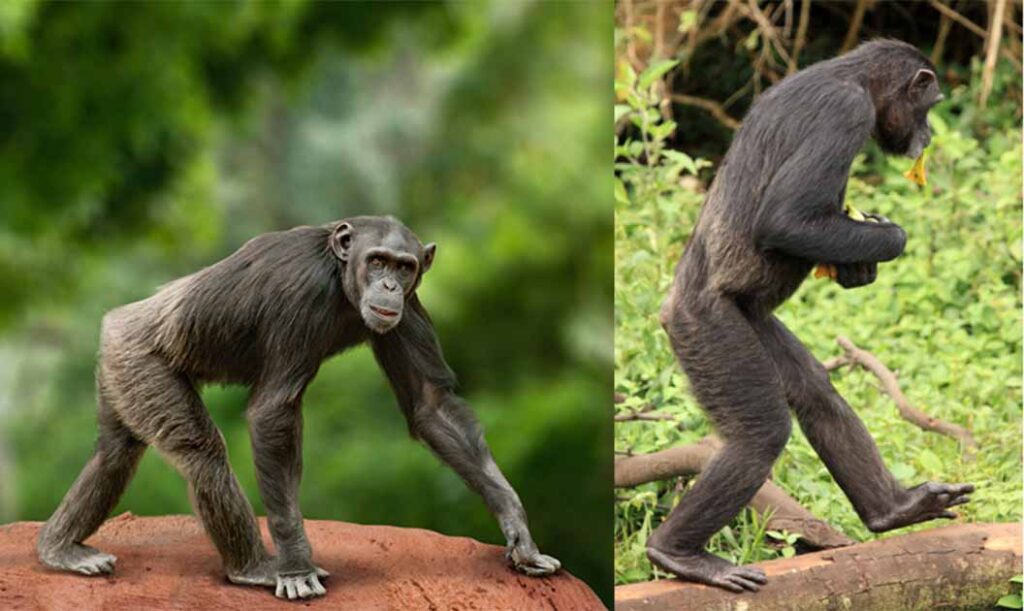

Researchers have concluded that the evolutionary shift to bipedalism took place in trees. In the image an adult male chimpanzee walks upright to navigate flexible branches in the open canopy, in behavior characteristic of the Issa Valley savanna-mosaic habitat. (Rhianna Drummond-Clarke/Science)

The Evolutionary Leap to Bipedalism

The term “savanna-mosaic” is used to describe a habitat that includes large mostly treeless areas of dry land interspersed with patches of dense forest. Knowing that humans evolved in this type of landscape suggests that they would have gained an advantage being able to walk across large open areas on two legs. This would have created evolutionary pressure that ultimately led to the transformative leap to bipedalism.

The point of this new study was to see if savanna-mosaic chimpanzees did in fact spend more time on the ground than chimpanzees living in other parts of Africa, given the greater availability of open grassland. The belief was that this would be the case, and this would indirectly support the idea that evolutionary pressures created by this type of environment would have helped encourage bipedalism in human ancestors.

But contrary to expectations, the scientists discovered that the Issa Valley chimpanzees spent just as much time in the trees as their forest-dwelling cousins, despite the ecological variations in their habitats.

The researchers discovered something else that was just as revealing. When observing the chimpanzees out in the open savanna, they expected to see them up on two legs and walking more frequently than while in the trees. But in fact, more than 85 percent of the incidents of bipedalism observed occurred when the chimpanzees were clambering about in the trees.

A chimpanzee walking upright. (Sam D’Cruz / Adobe Stock)

Walking Back Long-Cherished Theories of Human Evolution

The study authors assert that their findings are in direct contradiction to theories about prehistoric humans developing the ability to walk upright because they were spending so much time on open savanna land. “We naturally assumed that because Issa has fewer trees than typical tropical forests, where most chimpanzees live, we would see individuals more often on the ground than in the trees,” explained UCL anthropologist and study co-author Dr. Alex Piel, in a University College London press release.

“Moreover, because so many of the traditional drivers of bipedalism (such as carrying objects or seeing over tall grass, for example) are associated with being on the ground, we thought we’d naturally see more bipedalism here as well,” stressed Piel. “However, this is not what we found.”

Dr. Piel now believes that a significant loss of forest land in eastern Africa in the distant past did not impact human evolution in the way that had previously been assumed. “Our study suggests that the retreat of forests in the late Miocene-Pliocene era around five million years ago and the more open savanna habitats were in fact not a catalyst for the evolution of bipedalism,” he concluded. “Instead, trees probably remained essential to its evolution—with the search for food-producing trees a likely a driver of this trait.”

In other words, according to this theory it was the hunt for increasingly scarce forest-based food supplies that encouraged bipedalism. Developing this trait would have helped our ancient hominin ancestors climb more trees to greater heights, and therefore bipedalism offered an evolutionary advantage even to nearly full-time tree dwellers.

More Evidence for Tree-Walking Prehistoric Humans

While this new study has revolutionary implications, it is not the first research suggesting that prehistoric humans first walked in the trees. In a 2019 article published in the journal Nature, a team of scientists wrote about their discovery of a wholly unique ape that lived nearly 12 million years ago and moved about in a completely different way to any other hominin.

The scientists, who were affiliated with Eberhard Karls University in Tübingen, Germany, claimed that a fossilized ape that had been found during excavations in Bavaria possessed a hybrid-like mixture of human legs and arms that resembled those of an orangutan. The hypothesized that this animal would indeed have been capable of tree-top bipedal locomotion when necessary, possibly when attempting to flee from gigantic feline predators that could rapidly climb trees themselves.

The German researchers theorized that this fossilized ape, which they identified as a type of hominin known as Danuvius guggenmosi, could be a sort of missing link that could help fill in the evolutionary gap between ancient human ancestors who developed bipedal capabilities and their great ape cousins that remained on four legs permanently.

Bones from the hand of a male human ancestor Danuvius guggenmosi, which researchers claimed was a missing link in the evolutionary leap to bipedalism. (Christoph Jäckle / Nature)

Solving the Next Evolutionary Puzzle

While they’re certain their study has revealed something significant about human evolution, the scientists involved in the Issa Valley research project acknowledge that one big question remains unanswered. Why did human ancestors develop the capacity to walk on two legs while their close cousins in the great ape family continued to walk on all fours, using their knuckles to maintain their balance?

Presumably the evolutionary pressures that encouraged bipedalism in humans would have encouraged it in other primates as well. And yet bipedalism was a rare development that occurred only in a few ancient hominins which begs another question: Why do primates prefer to stay in the trees?

“To date, the numerous hypotheses for the evolution of bipedalism share the idea that hominins (human ancestors) came down from the trees and walked upright on the ground, especially in more arid, open habitats that lacked tree cover,” said study co-author Dr. Fiona Stewart, an anthropologist from University College London.

“Unfortunately, the traditional idea of fewer trees equals more terrestriality (land dwelling) just isn’t borne out with the Issa data,” she explained. “What we need to focus on now is how and why these chimpanzees spend so much time in the trees—and that is what we’ll focus on next on our way to piecing together this complex evolutionary puzzle.”