Roald Dahl was not an admirer of the Gloster Gladiator. “They have taut canvas wings, covered with magnificently inflammable dope, and underneath there are hundreds of small thin sticks, the kind you put under the logs for kindling, only these are drier and thinner,” wrote Dahl, the British novelist and short-story writer, creator of Willy Wonka and a Gloster Gladiator pilot himself. “If a clever man said, ‘I am going to build a big thing that will burn better and quicker than anything else in the world,’ and if he applied himself diligently to his task, he would probably finish up by building something very like a Gladiator.”

Dahl’s understanding of his airplane’s structure was lacking, since its wings were all metal, but he nearly died in a flaming crash of his own Gladiator in the North African desert, so we’ll give him some leeway.

The Gladiator—it had no nickname, was never called the Gladdy or the Blazing Breadbox—was the last British biplane fighter, an anomaly that the Air Ministry clung to out of both necessity and romanticism. As an aerobatic plaything for the finest flying club in the world—the boys of the RAF’s Volunteer Reserve prewar university squadrons at Cambridge and Oxford—there was no lovelier airplane.

In the 1930s, the RAF was lumbered with slow, draggy, open-cockpit biplane fighters like the Hawker Fury and Bristol Bulldog, which could trace their lineage to World War I. But relief was in sight: already under development were “the monoplane fighters,” which we now know as the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire. They were a reaction to the threat of what would become one of the finest piston-engine fighters of all time—Germany’s Messerschmitt Me-109. But “development” was another way of saying, “maybe next year…or two.” Something was needed in the interim.

The company that built the Gladiator was called Gloster. (Initially it was the Gloucester-shire Aircraft Company, until the Brits found that foreigners were pronouncing it “Glau-cess-der-shyer.” So they invented the briefer phonetic title.) It seems odd that Gloster created something so antediluvian as the Gladiator, for its very next design was the first British jet, the tubby little E28/39 Whittle-engine testbed. After that Gloster designed the only RAF jet to see combat in World War II, the Meteor.

The Gladiator’s designer was engineer Henry Philip Folland, who would eventually found his own aircraft company, best known today for the Folland Gnat light fighter and trainer that once served with the RAF Red Arrows display team. Folland had been the lead designer of the Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5, which was so fast and successful in combat that it is sometimes called the Spitfire of World War I. He went on to design several of the Gladiator’s predecessors—the Grebe, Gamecock and Gauntlet. With his Schneider Trophy contender, the Gloster IV float biplane, he acquired a reputation as a drag-deleting expert. With the Glad-iator, Folland brought the biplane fighter to the pinnacle of prewar excellence.

In 1930, the Air Ministry had issued a specification—what the U.S. would call a request for proposals—and they got a dozen relatively advanced biplane candidates, at least on paper. Unfortunately, the spec had urged the use of the Rolls-Royce Goshawk engine, a V-12 design that used evaporative cooling rather than straightforward liquid cooling. The theory was that having an engine turn its coolant into steam removed more heat than simply having it make hot water hotter. Maybe so, but the Goshawk turned out to be a lousy engine. For one thing, the cooling system didn’t work during high-G maneuvers. Nor did it help that steam cooling required a large condensing radiator atop the upper wing to turn the steam back into liquid. If a single rifle-caliber round punctured that, it could easily down the airplane.

Gloster had wisely steered clear of the Goshawk and instead worked on a private venture, upgrading its already-successful Gauntlet biplane fighter. The Gauntlet had a Bristol Jupiter nine-cylinder radial, but Bristol did a bit of engineering and turned the Jupiter into the very successful Mercury engine by shortening its stroke an inch and thus reducing the circumference of the engine, meaning less frontal-area drag. It also meant less power, but Bristol dealt with that by doing an unusual thing. Super-charged aircraft engines use their blowers to maintain sea-level power as altitude increases, but Bristol decided to give the Mercury some extra power by ground-boosting it—tuning the supercharger to work even at sea level. The Mercury also had four valves per cylinder—unusual for a radial.

In an attempt to reach the 250-mph top speed then beloved of the Air Ministry, Gloster strengthened the main spars and changed the biplane configuration from a two-bay design—two sets of interplane struts on each side of the fuselage—to a single-bay configuration. Eliminating four big struts and their yards of cables and rigging cleaned up the airplane substantially, as did simplifying the draggy landing gear. Straightforward Stearman-like Dowty dampers enclosed in nicely faired wooden legs were far cleaner than the multi-strutted Gauntlet design.

The one thing that clearly turned a Gauntlet into a Gladiator, however, was a fully enclosed cockpit with a sliding canopy—the first on any RAF fighter. Yet many photos of Gladiators in flight show that canopy slid wide open. Like early airline pilots who decried the Ford Trimotor because its enclosed cockpit kept them from feeling the wind on their cheeks (which is how, they claimed, it was possible to make coordinated turns), experienced RAF pilots felt constrained by a canopy. It limited their visibility, they said, and insulated them from their proper milieu. One Gladiator pilot claimed that he had tracked a bogey for miles before realizing that it was a fly strolling around the inside of his canopy. Nor did it help that a Gladiator’s cockpit often filled with engine fumes that needed to be blown away.

The canopy wasn’t the only Gladiator innovation that met with disapproval. The big biplane was the first British fighter to utilize flaps, though they were intended solely for landing. They were small but deployed from both sets of wings, so their total area was meaningful. Many old-timers wouldn’t touch them, complaining that they upset the airplane’s trim. Perhaps they felt that using the big pitch-trim wheel just to the left of the pilot’s seat was not their job.

The Gladiator prototype flew in September 1934 but did not enter service with the RAF until early 1937, and by then the RAF had already ordered its first Hurricanes, signaling the biplane’s impending obsolescence. Those early Mk.I Gladiators came armed with World War I Vickers and Lewis machine guns—two of the former in the fuselage sidewalls firing through the prop, plus a Lewis under each lower wing. The old .303-caliber popguns often jammed the instant the trigger was activated. Savvy Gladiator pilots carried rubber mallets with which to pound on the Vickers breeches, which extended back into the cockpit.

Why did aircraft guns jam so often back then? There were many reasons, but perhaps the most meaningful one is that machine guns were designed to operate in an upright, stable, 1G ground environment, often carefully belt-fed by second gunner. Bolt them onto a vibrating, cavorting, G-loaded airplane, and all of the finely machined sliding and rotating parts inside the breech get minutely twisted and racked by an airplane’s maneuvers and position. Nobody designed those guns to fire upside-down or sideways. A partial solution was to replace all four British guns with somewhat more modern Colt Brownings manufactured under license by Birmingham Small Arms, the company that went on to produce the classic BSA motorcycles of the 1950s.

The guns “actually fired bullets through the revolving propeller,” marveled Roald Dahl. “To me, this was about the greatest piece of magic I had ever seen in my life. I could simply not understand how two machine guns firing thousands of bullets could be synchronized to fire their bullets through a propeller revolving at thousands of revs a minute without hitting the propeller blades. I was told that it had something to do with a little oil pipe and that the propeller shaft communicated with the machine guns by sending pulses along the pipe, but more than that I cannot tell you.”

More than that one does not need, and it is a satisfying explanation, unlike the usual muttering about “interrupter gears.” Dahl, never a technologist, managed to give as brief and useful a description of gun/prop synchronization as one can imagine.

The Gladiator’s career was too short to allow for many variants to be developed, so there were only three near-identical versions of the airplane. The original Mk.I had an 840-hp Bristol Mercury driving a fat two-blade, fixed-pitch wooden prop, and the Mk.II received a more efficient three-blade metal prop, plus the Browning guns. The Royal Navy found itself without a fleet-defense fighter, so it got the Sea Gladiator. It had a strengthened tailcone and A-frame arrestor hook, and a pod holding an inflatable raft on its belly between the mainwheel struts, activated by a cable in the cockpit. The dinghy pod was well-located, since a ditched Gladiator would turn turtle the instant its landing gear hit the water, but it was asking a lot of a drowning and upside-down pilot to free himself from a flooded cockpit while remembering to find and pull the raft cable.

Gladiators had some tricky handling qualities, exacerbated by pilots unfamiliar with its relatively high wing loading and flapped landings. During the airplane’s introduction to squadron service, the accident rate was appalling. A brisk stall often led to a spin, which would go flat and become unrecoverable in unskilled hands. During combat maneuvering, Gladiators sometimes spun out of the fight (which might have been a good thing, considering some of its monoplane opponents). Intentional spinning at night was forbidden, and it probably should have been during daylight as well.

Still, the Gladiator was wonderfully aerobatic and became a popular air-display act during its brief late-1930s career when a trio of Gladiators flew formation maneuvers while “chained together” at the wingtips, in the words of one commentator. The chains were actually far more frangible tethers with breakaway fittings.

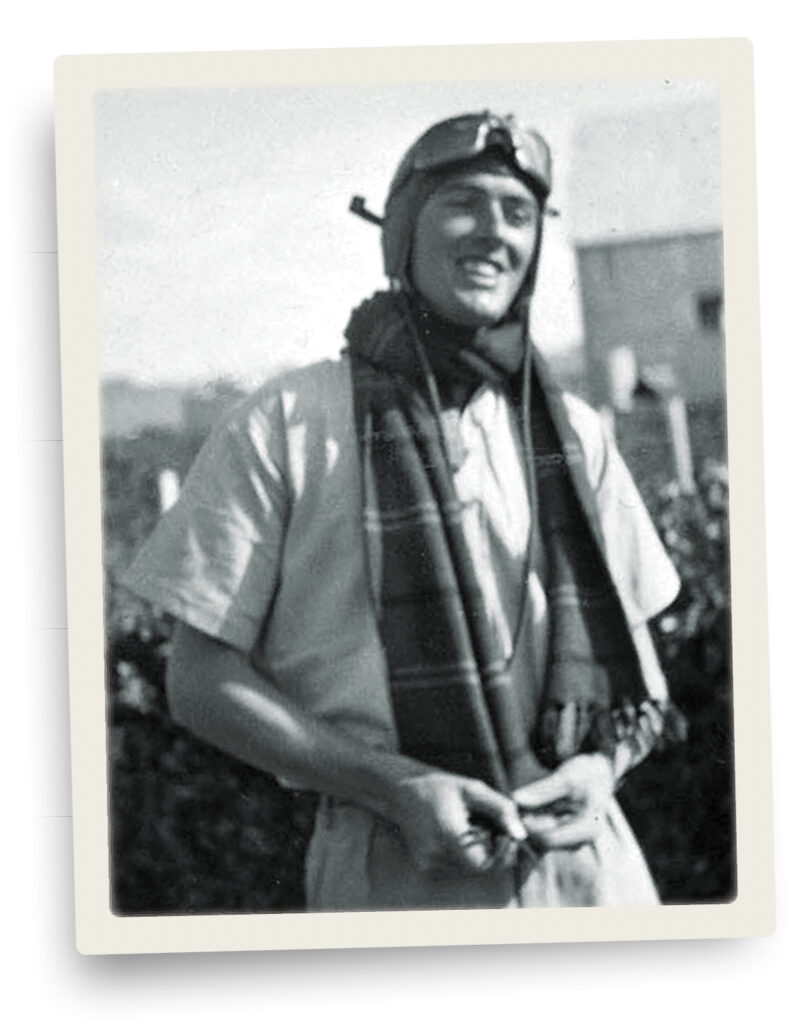

Dahl had his own concerns about flying the Gladiator, and he wondered, “Who will teach me to fly it? ‘Don’t be an ass [said his squadron commander]. How can anyone teach you when there’s only one cockpit? Just get in and do a few circuits and bumps and you’ll soon get the hang of it. You had better get all the practice you can because the next thing you know you’ll be dicing in the air with some clever little Italian who will be trying to shoot you down.’”

The Gladiator’s wartime career was necessarily brief and, despite some mythmaking, largely ineffectual. Not surprising, since there were few less-capable fighters in action, and all of Germany’s and Italy’s bombers easily outpaced it. The RAF usually sent Gladiators to war zones normally out of reach of Luftwaffe Me-109s. Only one Gladiator squadron participated in the Battle of Britain, and it was stationed in the southwest of England to protect the ports of Plymouth and Falmouth, which were beyond the range of German fighters. Its only contribution to that conflict was the interception of a force of Dornier Do-17 bombers and Messerschmitt Me-110 escorts at the end of September 1940. The Germans were too fast for the Gladiators, and two of the Dorniers bombed Plymouth unchecked. Though Gladiators notched victories against Italian Macchi C.200 and French Dewoitine D.520 monoplanes, there is no record of a Gladiator shooting down an Me-109.

The first Gladiator victory had already been scored by an American, Captain John “Buffalo” Wong, one of the 15 volunteers who flew for the Chinese against the Japanese more than two years before Claire Chennault formed the short-lived American Volunteer Group. In February 1938, Wong shot down an A5M Claude, the fixed-gear, open-cockpit predecessor of the Zero. (Some records credit him with two Claudes.)

Wong’s Chinese American squadronmate Arthur Chin became an ace, with eight victories before the U.S. even entered the war, and 6.5 of them were with the Gladiator. Chin receives credit as the first U.S. ace of World War II. One of his Gladiator victories involved ramming a Claude and then bailing out from his wrecked airplane. The apocryphal story is that he stripped a machine gun from the wreckage of his Gladiator and showed it to Chennault, then an aviation advisor to the Chinese, and asked if he could please have another Gladiator to go with it.

The ultimate Gladiator pilot was Flt. Lt. Marmaduke Thomas St. John “Pat” Pattle, a South African who scored at least 15 victories with Gladiators, first in Egypt and later in Greece. (The rest of his 50-plus shoot-downs were accomplished with Hurricanes.) “Usually outrun, often outgunned but seldom outmaneuvered,” reads one tribute to Pattle, arguably the most skilled and dogged of all Gladiator pilots.

Gladiators fought in the hands of a wide variety of export customers as well as the RAF, and they reached many war zones, including North Africa, Greece, the Middle East, France and Scandinavia. The Norway campaign was one of the Gladiator’s bloodiest battles, and for the RAF, it was a disaster.

A squadron of Gladiators flew to Norway from the carrier HMS Glorious to help blunt the German invasion in late April 1940, and they surprised the Germans by landing on a frozen lake in the country’s center. (The lake had been selected by Sqdn. Ldr. Whitney Straight, an American racecar driver who in the years before the war had won more international Grand Prix than any other American.) The Gladiators arrived without support personnel, and the pilots found themselves rearming and refueling their airplanes themselves with bitterly cold hands, often using milk cans supplied by local farmers for the fuel. The Luftwaffe reacted quickly with bombing raids, and the lake, already thawing in the spring weather, became increasingly cratered and unstable. After 48 hours of this, the Gladiators were finished as a fighting force, burnt out on the ground and sunk into the boggy water. The squadron hadn’t shot down a single Luftwaffe aircraft. The Air Ministry admitted that the Gladiators had been sent to Norway “as a token sacrifice.”

The squadron received another 18 Gladiators and returned to Norway, this time to an established airfield. They scored several victories over Heinkel 111s and possibly even a Focke-Wulf 200 Condor. Ultimately, what remained of the squadron flew back to the Glorious, despite the Gladiators having no arresting hooks nor any pilots who had made deck landings. Soon after the carrier sailed, the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau sank it and all but two of the Gladiator pilots aboard. It was the end of the Gladiator’s Norwegian adventure.

Nobody can write an account of the Gladiator’s career without extolling the feats of the most famous of all Gladiators, the six airplanes that went by the names of Faith, Hope and Charity. Starting in June 1940 they defended the Mediterranean island of Malta against the Regia Aeronautica, the Italian air force, and unfortunately, their story has become a mix of legend and reality. There were no individual Gladiators named Faith, Hope or Charity, and the honorific was applied to the entire flight of fighters by a Maltese newspaper well after the island had been saved from defeat, largely by Hurricanes and Spitfires. (The remains of a Gladiator on display at Malta’s National War Museum purports to be from Faith.)

Yet the Malta Gladiators were immensely reassuring to the Maltese as the biplanes stood watch from dawn to dusk and frequently barreled off to intercept incoming Savoia-Marchettis and Capronis. The only way they could attack the bombers was to climb above them and pick up speed in a dive, so they snarled their way upward, full throttle and superchargers set to max (officially forbidden). Their high-angle, low-forward-speed climbs overheated and destroyed their engines, but to the Maltese, they were brave pit bulls lunging to the ends of their chains.

It’s often forgotten that, not counting trainers, there were at least two dozen types of biplanes used on the front lines during World War II. Everyone remembers the Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber—the Stringbag—but other biplane fighters included Polikarpov I-15s, Avia B-534s, Hawker Furies and particularly Fiat CR.42 Falco biplanes, the Gladiator’s most evenly matched rival.

The Falco was in fact a sesquiplane, not a biplane; it had lower wings of less than half the area of the upper wing. It also had an open cockpit and fixed landing gear, yet it was about 15 mph faster than the Gladiator. The Gloster was more maneuverable than the Italian fighter, particularly in a turning fight. The Gladiator’s biggest advantage was that it carried a radio with about five miles of air-to-air range, allowing coordinated attacks while the Italian pilots could only gesture and nod their heads. Gladiators had a 1.2-to-1 victory ratio over CR.42s—much the same as the Me-109’s advantage over the Spitfire during the Battle of Britain: close enough to call it even.

After the war, Gladiators were essentially worthless. British collector Vivian Bellamy bought two hulks for a pound sterling apiece in 1951 and created a single flyable airplane, which he sold to the Gloster company for £50. That airplane was later restored and today is part of the Shuttleworth Collection in Bedfordshire, England. It is one of only two flying Gladiators remaining. In September 2021, the Malta Aviation Museum announced plans to create a flyable replica built around one small part salvaged from what they claim was the sunken Gladiator Charity, but that project seems to be in limbo.

The Gloster Gladiator: honor this cranky and archaic yet iconic and innovative fighter, but offer a prayer for all the pilots who had to go into combat with it.