The German zeppelin Hindenburg flies over Manhattan on May 6, 1937. A few hours later, the ship burst into flames in an attempt to land at Lakehurst, New Jersey.

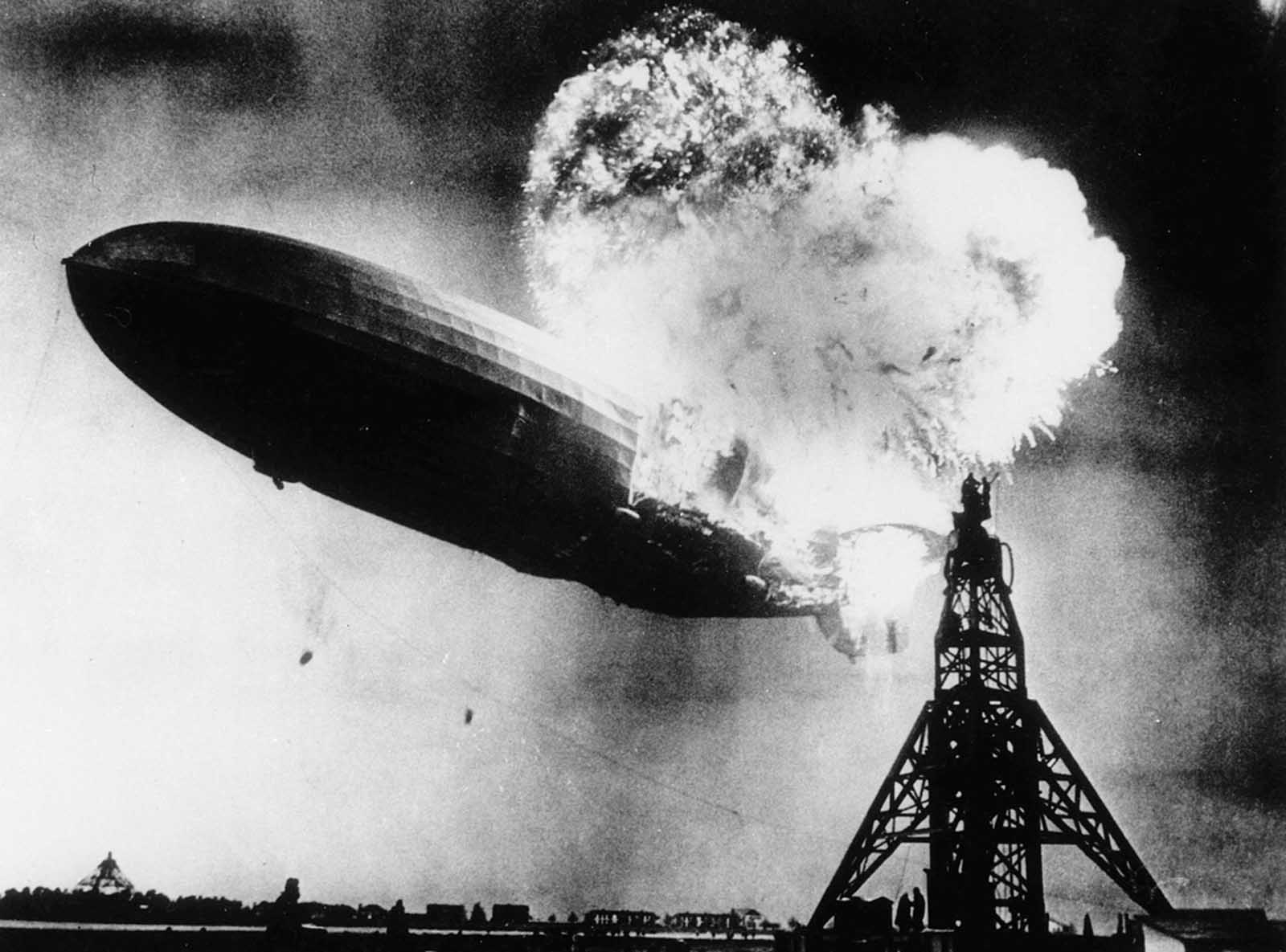

The Hindenburg disaster at Lakehurst, New Jersey on May 6, 1937 brought an end to the age of the rigid airship. The disaster killed 35 persons on the airship, and one member of the ground crew, but miraculously 62 of the 97 passengers and crew survived.

After more than 30 years of passenger travel on commercial zeppelins — in which tens of thousands of passengers flew over a million miles, on more than 2,000 flights, without a single injury — the era of the passenger airship came to an end in a few fiery minutes.

Almost 80 years of research and scientific tests support the same conclusion reached by the original German and American accident investigations in 1937: It seems clear that the Hindenburg disaster was caused by an electrostatic discharge (i.e., a spark) that ignited leaking hydrogen.

The spark was most likely caused by a difference in electric potential between the airship and the surrounding air: The airship was approximately 60 meters (about 200 feet) above the airfield in an electrically charged atmosphere, but the ship’s metal framework was grounded by its landing line.

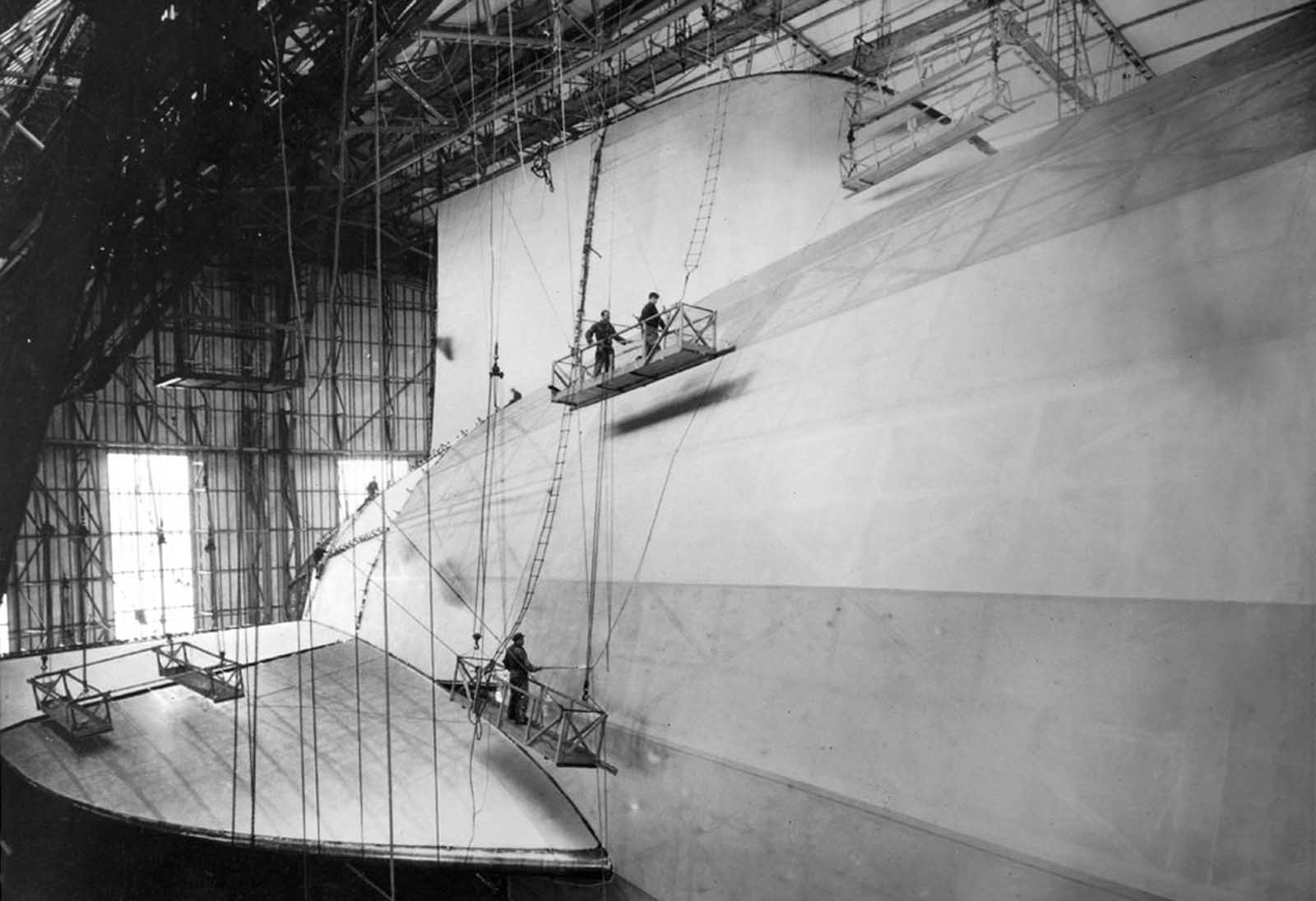

Finishing touches are applied to the A/S Hindenburg in the huge German construction hangar at Friedrichshafen. Workmen, dwarfed in comparison with the ship’s huge tail surfaces, are chemically treating the fabric covering the huge hull.

The difference in electric potential likely caused a spark to jump from the ship’s fabric covering (which had the ability to hold a charge) to the ship’s framework (which was grounded through the landing line). A somewhat less likely but still plausible theory attributes the spark to coronal discharge, more commonly known as St. Elmo’s Fire.

The cause of the hydrogen leak is more of a mystery, but we know the ship experienced a significant leakage of hydrogen before the disaster. No evidence of sabotage was ever found, and no convincing theory of sabotaged has ever been advanced.

One thing is clear: the disaster had nothing to do with the zeppelin’s fabric covering. Hindenburg was just one of many hydrogen airships destroyed by fire because of their flammable lifting gas, and suggestions about the alleged flammability of the ship’s outer covering have been repeatedly debunked. The simple truth is that Hindenburg was destroyed in 32 seconds because it was inflated with hydrogen.

The disaster was the subject of spectacular newsreel coverage, photographs, and Herbert Morrison’s recorded radio eyewitness reports from the landing field, which were broadcast the next day.

The event shattered public confidence in the giant, passenger-carrying rigid airship and marked the abrupt end of the airship era.

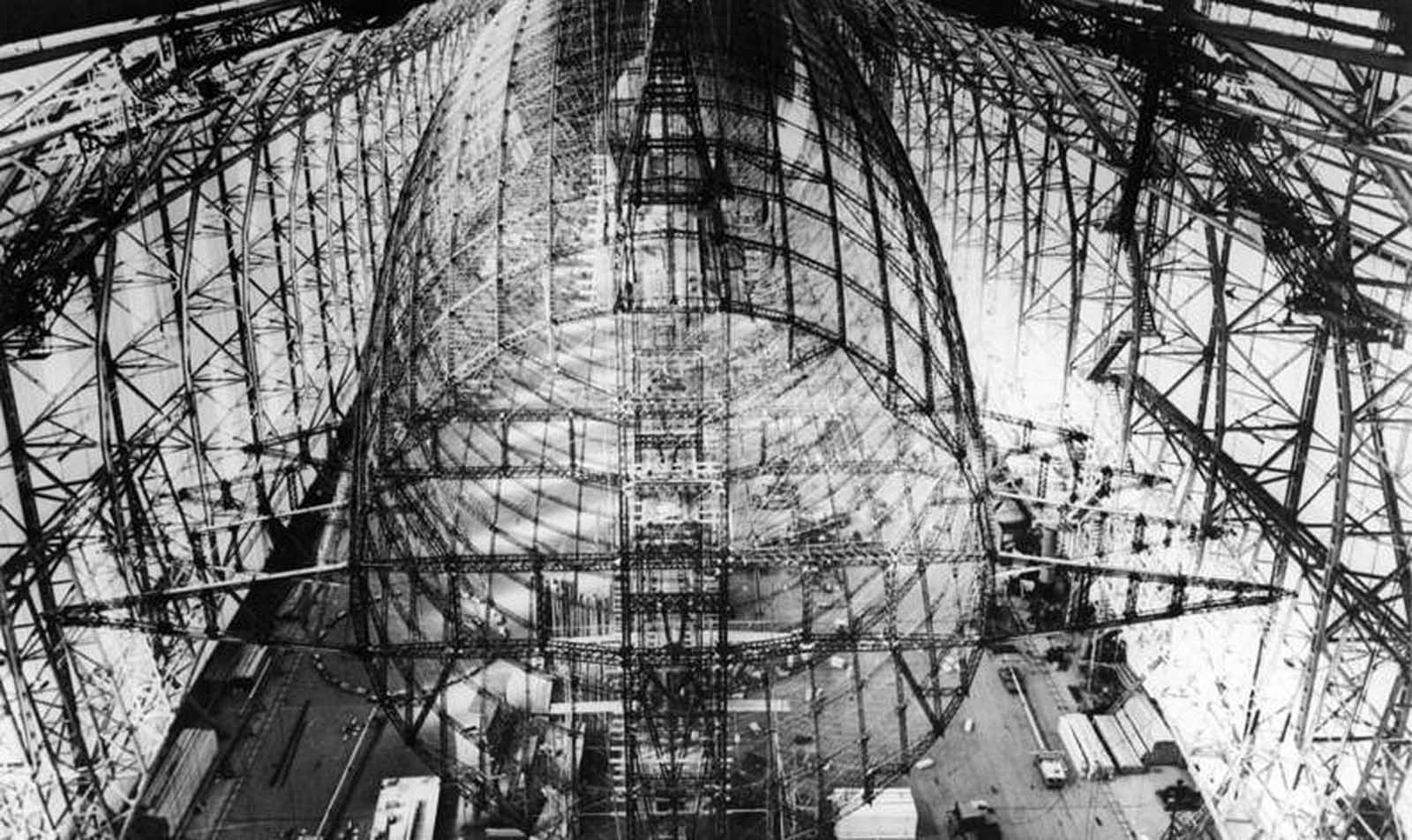

The steel skeleton of “LZ 129”, the new German airship, under construction in Friedrichshafen. The airship would later be named after the late Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, former President of Germany.

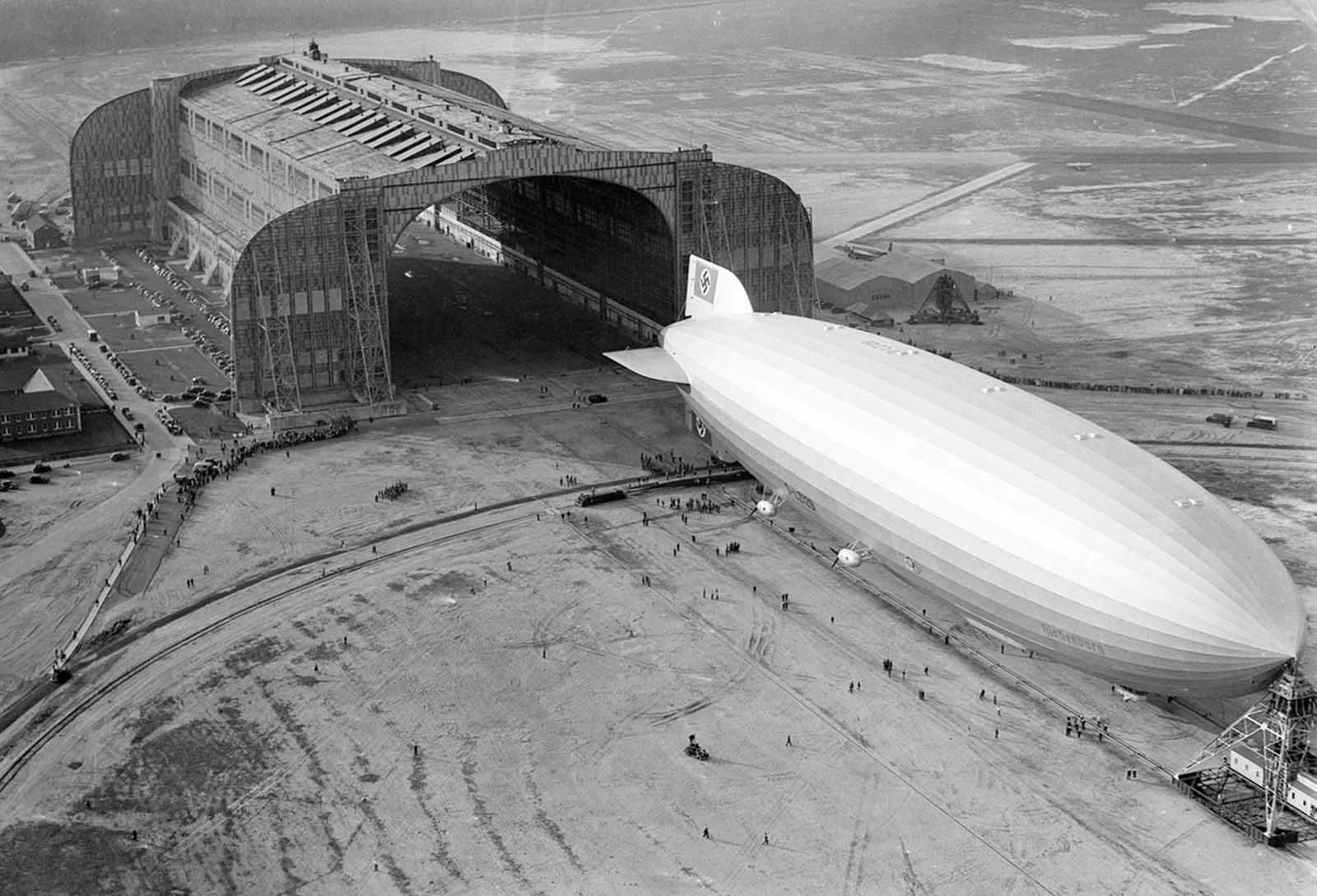

The Hindenburg dumps water to ensure a smoother landing in Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 9, 1936. The airship made 17 round trips across the Atlantic Ocean in 1936, transporting 2,600 passengers in comfort at speeds up to 135 km/h (85 mph). The Zeppelin Company began constructing the Hindenburg in 1931, several years before Adolf Hitler’s appointment as German Chancellor. For the 14 months it operated, the airship flew under the newly-changed German national flag, the swastika flag of the Nazi Party.

Spectators and ground crew surround the gondola of the Hindenburg as the lighter-than-air ship prepares to depart the U.S. Naval Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 11, 1936, on a return trip to Germany.

A color photograph of the dining room aboard the Hindenburg.

Passengers in the dining room of the Hindenburg, in April of 1936.

The Hindenburg flies over the Boston Common in Boston, Massachusetts in 1936. Another small plane can also be seen at top right.

A U.S. Coast Guard plane escorts the Hindenburg to a landing at Lakehurst, New Jersey, on its inaugural flight between Freidrichshafen and Lakehurst in 1936.

The giant German zeppelin Hindenburg, in Lakehurst, New Jersey, in May of 1936. The Olympic rings on the side were promoting the 1936 Berlin Summer Olympics.

The Hindenburg trundles into the U.S. Navy hangar, its nose hooked to the mobile mooring tower, at Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 9, 1936. The rigid airship had just set a record for its first north Atlantic crossing, the first leg of ten scheduled round trips between Germany and America.

The German dirigible Hindenburg, just before it crashed before landing at the U.S. Naval Station in Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 6, 1937.

At approximately 7:25 p.m. local time, the German zeppelin Hindenburg burst into flames as it nosed toward the mooring post at the Naval Air Station in Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 6, 1937. The airship was still some 200 feet above the ground.

The Hindenburg quickly went up in flames — less than a minute passed between the first signs of trouble and complete disaster. This image captures a moment between the second and third explosions before the airship hit the ground.

As the lifting Hydrogen gas burned and escaped from the rear of the Hindenburg, the tail dropped to the ground, sending a burst of flame punching through the nose. Ground crew below scatter to flee the inferno.

A survivor flees the collapsing structure of the airship Hindenburg.

Major Hans Hugo Witt of the German Luftwaffe, who was severely burned in the Hindenburg disaster, is seen as he is transferred from Paul Kimball Hospital in Lakewood, New Jersey, to another area hospital, on May 7, 1937

An unidentified woman survivor is led from the scene of the Hindenburg disaster at the U.S. Naval Station in Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 6, 1937.

Adolf Fisher, an injured mechanic from the German airship Hindenburg, is transferred from Paul Kimball Hospital in Lakewood, New Jersey, to an ambulance going to another area hospital, on May 7, 1937.

Members of the U.S. Navy Board of Inquiry inspect the wreckage of the German zeppelin Hindenburg on the field in New Jersey, on May 8, 1937.

In New York City, funeral services for the 28 Germans who lost their lives in the Hindenburg disaster are held on the Hamburg-American pier, on May 11, 1937. About 10,000 members of German organizations lined the pier.

German soldiers give the salute as they stand beside the casket of Capt. Ernest A. Lehmann, former commander of the zeppelin Hindenburg, during funeral services held on the Hamburg-American pier in New York City, on May 11, 1937. The swastika-draped caskets were placed on board the SS Hamburg for their return to Europe.

Surviving members of the crew aboard the ill-fated German zeppelin Hindenburg are photographed at the Naval Air station in Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 7, 1937. Rudolph Sauter, chief engineer, is at center wearing white cap; behind him is Heinrich Kubis, a steward; Heinrich Bauer, watch officer, is third from right wearing black cap; and 13-year-old Werner Franz, cabin boy, is center front row. Several members of the airship’s crew are wearing U.S. Marine summer clothing furnished them to replace clothing burned from many of their bodies as they escaped from the flaming dirigible.

An aerial view of the wreckage of the Hindenburg airship near the hangar at the Naval Air station in Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 7, 1937.