When no one in the United States would train her, Bessie Coleman enrolled in a prestigious flight school in France — and became a fearless stunt pilot known across the world.

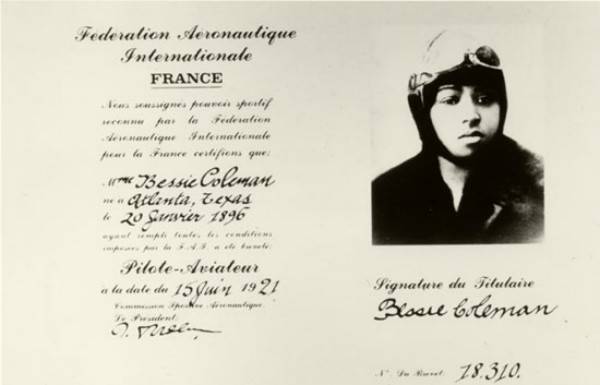

In 1921, Bessie Coleman became the first Black woman in America to be awarded a pilot’s license. Coleman’s journey to the cockpit, however, was no breeze.

Based on her gender and color, Coleman was denied admission to all the aviation schools she applied to in the United States. To achieve her dream she saved money, learned French, and traveled to Crotoy, France, where she enrolled in a flight school.

Wikimedia CommonsBessie Coleman and her plane in 1922.

When she returned to America, she took crowds by storm performing mid-flight tricks. She reached remarkable heights for a woman of her time through her bravery and persistence, but in 1926, it all came crashing down with her tragic demise.

Bessie Coleman Sees An Opportunity In The Skies

Elizabeth Coleman was born the 10th of 12 children in rural Texas on January 26, 1892. Her mother was Black and her father was Black and Cherokee — which made Bessie Coleman the first woman of Native American descent to take to the skies in America, as well.

Both of Coleman’s parents were sharecroppers who couldn’t read, but she walked four miles every day to attend a one-room segregated school where she learned to read and excelled in math.

Unlike many women of any race during her time, Coleman even attended college at the Langston Industrial College, now Langston University in Oklahoma. She could only afford one semester and was forced to drop out. Then, in 1916, she moved with her brother to Chicago.

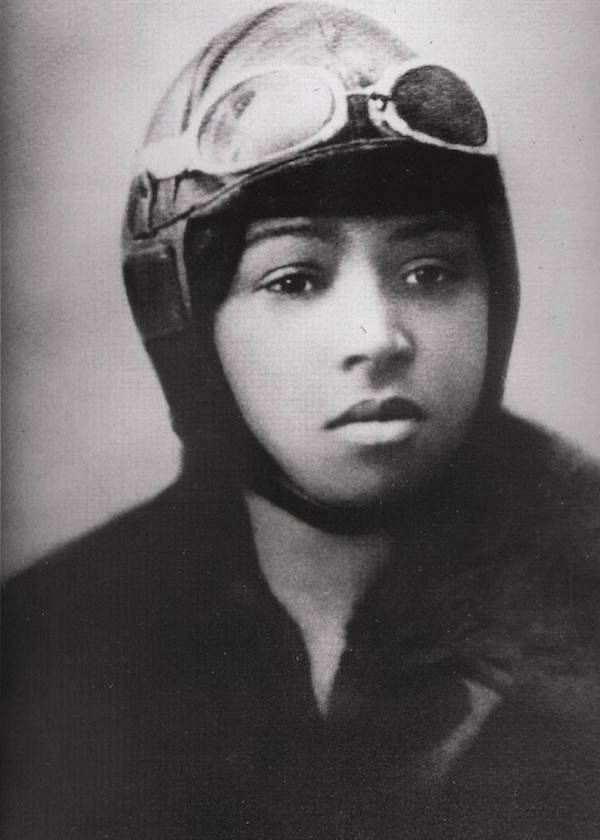

Wikimedia CommonsBessie Coleman in 1923.

Bessie Coleman took up work as a manicurist and made a reputation for herself as one of the fastest manicurists on her side of town. She was working at the White Sox Barber Shop when World War I fighter pilots began making headlines.

According to a biography about Coleman, her older brother had served in the Air Force in France and teased her about how women there had more freedoms. He said they could even fly planes. The notion struck Coleman and she began saving money for pilot school.

But no school in the United States would teach her, so Bessie Coleman resolved to make her way to France where she enrolled in the famous flight school, École d’Aviation des Frères Caudron. She was the only student of color in her class.

Smithsonian National Air and Space MuseumHer 1921 pilot license. When Bessie Coleman died in 1926, she had been performing for only five years.

Coleman learned to fly on the Nieuport 82 biplane, a tenuous vehicle with a steering system that consisted of a vertical stick the thickness of a baseball bat and a rudder bar under the pilot’s feet.

In seven months, Bessie Coleman couldn’t just fly, but she could do spins, parachute from the cockpit, and walk out onto the wings of the plane.

In June 1921, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale awarded Coleman an international pilot license, making her the first African American woman to have done so. In September of that year, Coleman headed to New York where she became a media sensation.

‘Queen Bess’ Only Performed For Integrated Crowds

Bessie Coleman was hailed as “a full-fledged aviatrix, the first of her race” and was honored at a musical in New York, where the entire audience, including the several hundred white people in the orchestra seats, rose to applaud her accomplishment.

But as the age of commercial flying was still a decade away, Coleman’s only way to make a living as a pilot was to perform for audiences as a stunt flier. And to do that, she needed more training. She spent a year in France, Germany, and the Netherlands completing courses in stunt flying before returning to the states as a headliner.

The aviatrix held fantastic shows where she performed daring stunts thousands of feet in the air. Her audiences numbered in the thousands and Coleman made sure that those audiences were racially integrated. Indeed, she reportedly only performed for crowds that were allowed to go through the same entrance.

She garnered a reputation as a brazen and glamorous woman and mingled with African Prince Kojo from the Kingdom of Dahomey, the beautiful singer Josephine Baker (who received her own pilot’s license in 1933), and actor William “Bojangles” Robinson.

Public DomainA poster advertises the arrival of Bessie Coleman in Ohio for a daring show.

Her life was even going to be the subject of a Hollywood film, but after Bessie Coleman learned that the director wanted to present her early life as one of poverty, she declined. “No Uncle Tom stuff for me!” she reportedly told Billboard magazine.

The fame didn’t come without incident, however. During one performance before 10,000 people in 1923, Coleman nose-dived from 300 feet, crashing into the ground. She came out of the accident relatively unscathed, but her dare-devilish tricks had to be hung up for a time.

Her return to the skies three years later would be her last.

The Tragic Death Of Bessie Coleman

Wikimedia CommonsThe death of Bessie Coleman made national headlines.

After years of touring as a speaker and lecturer and taking to the skies less frequently, Bessie Coleman planned an air show in Florida for May 1926.

The day before the show, Coleman went on a practice run with a young pilot named William Wills in Jacksonville. While airborne, she wasn’t strapped into the craft as she looked for safe places to parachute down to during the show.

Then, 10 minutes into the flight the engine stopped working. The plane was in the middle of a dive, and Coleman was ejected from the plane, falling 2,000 feet to her death. She died immediately on impact with the Earth.

Wills went down with the plane, also dying on impact.

FlickrThe Bessie Coleman stamp, released in 1995.

Coleman’s demise made national headlines, though her co-pilot Wills reportedly made more headlines because of his race. Nonetheless, close to 5,000 people came to her memorial in Jacksonville. Her body went on to Orlando and Chicago, where thousands more came out to mourn her and honor her incredible legacy. Intersectional civil rights activist Ida B. Wells famously spoke at her funeral in Chicago.

Despite Bessie Coleman’s death, her story is a lasting one.

In 1992, the Chicago City Council requested a postage stamp in her honor, stating, “Bessie Coleman continues to inspire untold thousands even millions of young persons with her sense of adventure, her positive attitude, and her determination to succeed.” The Bessie Coleman stamp was released in 1995. In 2006, she was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

As for Bessie Coleman’s desire and will to become a pilot in a time when she had little rights, she once said, “The air is the only place free from prejudices.”