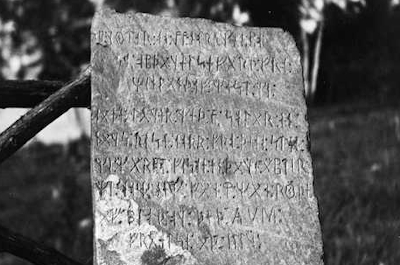

The Kensington Runestone is a gravestone-sized slab of hard, gray sandstone called graywacke into which Scandinavian runes are cut. It stands on display in Alexandria, Minnesota, as either a unique record of Norse exploration of North America or of Minnesota’s most brilliant and durable hoax.

Minnesota historian Theodore Blegen wrote in 1968 that “few questions in American history have stirred so much curiosity or provoked such extended discussions” as the Kensington Runestone. There are two uncontested facts. Swedish immigrant Olof Ohman came to Douglas County, Minnesota, in 1879. While clearing land on his farm near Kensington in the fall of 1898, he turned up a slab of rock with symbols carved on the side and underside. These markings were later identified as Scandinavian runic writing.

The generally accepted translation of those runes reads: “We are 8 Goths [Swedes] and 22 Norwegians on an exploration journey from Vinland through the West. We had camp by a lake with 2 skerries [small rocky islands] one day’s journey north from this stone. We were out and fished one day. After we came home we found 10 of our men red with blood and dead. AVM [Ave Virgo Maria, or Hail, Virgin Mary] save us from evil. We have 10 of our party by the sea to look after our ships, 14 days’ journey from this island. Year 1362.”

If the inscription is genuine it places Norse seafarers deep in the North American continent 130 years before Columbus reached the West Indies, and tells a story otherwise unknown.

The details of the stone’s geology, discovery, carving, and weathering, and the personality, education, writings, and possessions of its finder have been dissected, analyzed, and debated for more than a century. There are four main controversies over the stone’s authenticity.

The first controversy centers on the plausibility of the story. For the party’s ships to lie fourteen days’ journey from Alexandria, the only possible route is south from Hudson Bay. That distance is nearly 800 miles by direct line, longer by river and portage—a distance difficult to manage in fourteen days. The route is “through the west” from a “Vinland” whose location in 1362, if any, is unknown. No other record of this expedition has been found. Why would explorers who had just suffered a massacre stop to carve — in well-crafted, even, and orderly characters — a stone inscription?

The writing and language of the text are questionable. Experts first analyzed the runic writing in 1899. They dismissed it as a fake, citing too many discrepancies in form and vocabulary from the known languages of fourteenth-century Scandinavia. Most experts since then have agreed.

Finally, who was responsible for the alleged hoax? If the inscription is a fake, it must have been done by someone with knowledge of old Scandinavian language and runes, the ability to carve in stone, and the nerve to carry out the prank. The most likely perpetrator was Olof Ohman. Ohman had little education but owned a small library that included information about runes. His friend, former pastor Sven Fogelblad, may have had knowledge of runes and, like Ohman, may have sought to try to fool academics, whom both men reportedly disliked. Ohman never admitted to a hoax.

The Kensington Runestone has provoked a host of scholarly and popular articles and books. The Minnesota Historical Society library carries more than forty titles on the subject. The slab has been examined in Europe and displayed at the Smithsonian Institution and the 1965 New York World’s Fair. Expert opinion favors the conclusion that the inscription is not authentic, but the majority view asks the question: if a hoax, then who, how, when, and why? Definitive answers have so far proved beyond reach.