A New Jersey judge has denied an amateur investigator’s efforts to reexamine the evidence that was used to convict Bruno Richard Hauptmann for the 1932 kidnapping and killing of “the Lindbergh Baby,” a.k.a. Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., the toddler son of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh.

Earlier this year, New Jersey Monthly reported that Margaret Sudhakar, described as a “freelance researcher from Princeton,” was attempting to gain access to crucial pieces of evidence that had been used to secure the conviction and execution of Hauptmann during the 1935 Lindbergh Baby court case, often referred to as the “Trial of the Century.”

Sudhakar was hoping to submit key pieces of evidence, including the envelopes that contained the ransom notes; the infamous ladder used in the Lindbergh Baby kidnapping; and the kind of DNA analysis that simply didn’t exist in the mid-1930s. (Back then, investigators relied on handwriting analysis, and even a “wood technologist.”)

Sudhakar wrote to the state’s Superior Court, per New Jersey Monthly:

“The time for speculation about the New Jersey State Police’s most famous case is over. The time for answers is upon us. The answers to the most basic questions of this case, including who sealed the envelopes, who licked the stamps and who made the ladder, can all be obtained with modern day forensics at no cost to the state of New Jersey.’’

But Judge Robert Lougy has rejected the effort, dismissing Sudhakar’s claim that New Jersey’s open record law allowed her to submit historic objects to, as New Jersey Monthly puts it, tests that could “permanently alter” the objects. In Lougy’s own words, the open record law “is not the vehicle by which a citizen can march up to a museum and demand that the custodians of historical artifacts and documents surrender the state’s treasures for analysis, alteration and destruction.”

Why was Sudhakar seeking this evidence in the first place? Why bother digging into the conviction of a man who died (at the hands of the state) nearly 90 years ago? What makes the mysterious Lindbergh Baby kidnapping, and subsequent conviction of its alleged perpetrator, an enduring object of intense fascination, nearly a century later? For that, we must understand not only the famous trial that captivated America, but also the America that was captivated by that trial.

What Happened to the Lindbergh Baby?

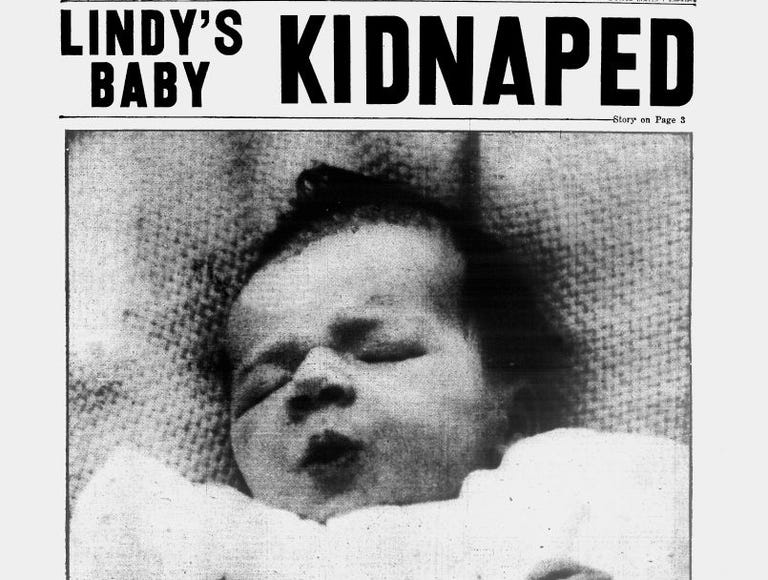

On March 1, 1932, at approximately 9 p.m., a kidnapper crawled through the window of a home in Hopewell, New Jersey using a wooden ladder. While the parents sat downstairs, blissfully unaware, the kidnapper absconded with the baby. An hour later, the family’s nurse entered the baby’s room to find no child—just an open window and a poorly written ransom note that read:

“Dear Sir,Have 50,000$ redy 25000$ in 20$ bills 15000$ in 10$ bills and 10000$ in 5$ bills. After 2-4 days will inform you were to deliver the Mony.We warn you for making anyding public or for notify the Polise the child is in gut care.

Indication for all letters are singnature and 3 holds.”

It’s important to remember that at the time, kidnappings were not all that uncommon. In the book The Snatch Racket: The Kidnapping Epidemic That Terrorized 1930s America, author Carolyn Cox notes that roughly 3,000 kidnappings for ransom were perpetrated across the country in just 1932 alone.

But we don’t talk about 2,999 of those kidnappings. We never hear about them. We don’t question the tactics used by the FBI to find “their man” and convict them. And we certainly don’t have people going to court trying to DNA-test their ransom notes.

Because 2,999 of those kidnappings didn’t involve the most famous man in America.

Who Was Charles Lindbergh?

It cannot be overstated just how famous Charles Lindbergh was in 1932. Five years earlier, in 1927, Lindbergh became the first aviator to make a non-stop solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean, taking the single-engine Spirit of St. Louis from New York to Paris. His achievement put him on the cover of every newspaper and magazine.

Lindbergh inspired songs like “Lindbergh (The Eagle of the U.S.A.)” and “Lucky Lindy,” and may have even inspired a popular dance (the “Lindy Hop,” though the origin is disputed). Lindbergh was so celebrated and beloved that in the first Mickey Mouse cartoon ever produced, Plane Crazy, Mickey can be seen admiring an image of Lindbergh, and even takes to the skies in imitation of the famed aviator.

Lindbergh was decorated in the U.S. and abroad, being awarded the Medal of Honor, Distinguished Flying Cross, and eventually a Pulitzer Prize in America; an Air Force Cross in the U.K.; a Commander of the Legion of Honor in France; and a Knight of the Order of Leopold in Belgium.

Lindbergh would also, in 1938, receive the Order of the German Eagle with Star from Hermann Göring on behalf of Adolf Hitler. And Lindbergh’s sympathies toward the goals of the Nazi state, as a prominent member of the America First Committee that opposed efforts to bring the U.S. into World War II, would tarnish his reputation in the 1940s and onward (and would play into some conspiracy theories around the kidnapping).

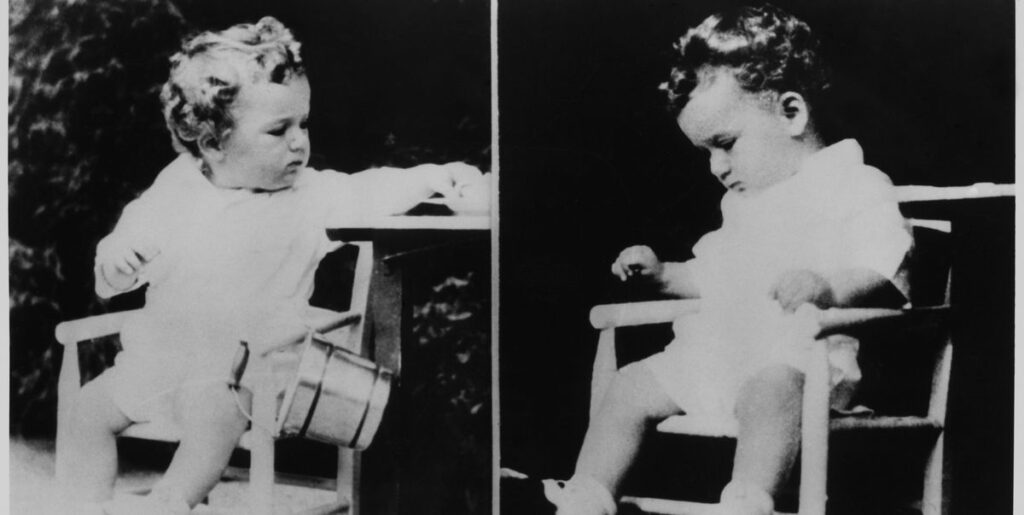

But at the time of the Lindbergh Baby kidnapping, Lindbergh was American royalty, admired and unimpeachable. And when America’s king of the skies and his bride, the wealthy writer Anne Morrow Lindbergh, announced that they had had a son, the boy was more than just another celebrity baby.

Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was seen as America’s child, treated as the heir to, well, the very air that Lindbergh was seen as having conquered. If Lindbergh was the “Lone Eagle,” as he had been so called, then Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was “The Eaglet.”

Why Was the Lindbergh Baby Kidnapped?

On March 1, 1932, “The Eaglet” was discovered to be missing. As Biography notes, “though there were traces of forced entry, including a broken ladder and footprints on the ground beneath the nursery window, there was nothing immediately useful to either the local Hopewell police or the New Jersey State Police” in the immediate aftermath.

On March 2, “word had gotten out about the kidnapping, drawing scores of newspaper journalists, well-wishers, and unsolicited volunteers to the Lindbergh residence. The visitors just about wrecked the crime scene and made further retrieval of evidence impossible.”

By March 3, as J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI became involved in the investigation, the movement began to try to pay the ransom, and track down both the Lindbergh Baby and whomever had taken him. Charles Lindbergh himself, however, remained heavily involved in the investigation, and his own tactics included collecting (and perhaps coordinating) the statements of his staff, as well as accepting “help from associates with connections to organized crime” and working with “a retired school principal in the Bronx named Dr. John F. Condon,” according to Biography.

Condon insisted upon involving himself in the actual payment of the ransom, a chaotic affair involving a shadowy figure named “Cemetery John,” the delivery of the clothing Charles Jr. had been wearing (freshly laundered by the kidnappers), and the false revelation that the Lindbergh Baby “could be found in Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, on a boat called the Nellie.”

Sadly, the Eaglet would not be found in Martha’s Vineyard. Nor anywhere in Massachusetts. Because on May 12, 1932, 72 days after Charles Jr. had first been reported as missing, the child’s body was found “alongside a highway near the Lindbergh estate.” New Jersey State Police Chief H. Norman Schwarzkopf noted that the deceased child’s injuries indicated that they were caused “…with the purpose of causing instant death.”

The crime had changed from mere kidnapping to murder. Americans glued to their newspapers and radios adjusted their energy from “praying for a safe return” to “calling for bloody vengeance.” The people who struck down the Lindbergh Baby needed to be found, and found quickly, by the proper authorities, lest lynch mobs begin to spring up around the country, targeting whoever it was deemed convenient to blame and ultimately kill in Charles Jr.’s name.

But it would take two years before the FBI would find their man. And to this day, some argue that a lynch mob looking for somebody to blame is precisely what the so-called “Trial of the Century” turned into.

Who Kidnapped and Killed the Lindbergh Baby?

There’s no denying that Bruno Richard Hauptmann had at least some of the Lindbergh Baby ransom money. Sixteen of the gold certificates that were used as part of the ransom were discovered as having been spent in the area of Manhattan’s Upper East Side, “a major enclave of German immigrants and their first-generation descendants,” according to Biography. This squared with the investigators’ theory that, because of the particular misspellings in the ransom notes, “they were written by someone from Germany who spoke limited English.”

But the real breakthrough came when it was discovered that one of the certificates had a license plate number scrawled on it. As it turns out, the cashier who had received it as payment thought the customer who gave it was suspicious. Not in the Lindbergh Baby kidnapping, but rather, of passing off a phony bill. Investigators were able to trace the license plate number to Bruno Richard Hauptmann.

Upon later searching Hauptmann’s home, investigators found more of the gold notes, as well as the phone number and address for Dr. John F. Condon scrawled on a cabinet door. Hauptmann would claim that the notes had been left behind by a friend, Isidor Fisch, who had left to return to Germany. As for the number, Hauptmann conceded that he might have copied it from a story in the newspaper, but couldn’t truly recall doing so.

And just as the scene of the crime was reportedly tampered with prior to the FBI’s arrival there, so, too, was Hauptmann’s home; we know of at least one reporter who entered the premises before the investigators arrived. (Reporter Mabel Greene boasts of having beaten police to Hauptmann’s home in her essay “Beating the Deadline” in the 1939 collection Writing Up the News: Behind the Scenes of the Great Newspapers.)

Indeed, there was no concrete evidence linking Hauptmann to the kidnapping, nor the killing, of the Lindbergh Baby. No fingerprints for Hauptmann were ever found on the ladder or the ransom note, nor anywhere in the nursery. Prosecutors had to rely solely on circumstantial evidence in order to secure their conviction. But as Supreme Court Justice Thomas W. Trenchard noted, “The crime of murder is not one which is always committed in the presence of witnesses, and if not so committed, it must be established by circumstantial evidence or not at all.”

Hauptmann was convicted of the crime, and put to death in the electric chair on April 3, 1936.

Why Is the Lindbergh Baby’s Kidnapping and Murder Still a Mystery?

So, why is anyone still trying to relitigate the Lindbergh Baby’s kidnapping and murder 90 years later? Part of it is the circumstantial nature of the evidence, and there certainly is a lot of it: Hauptmann possessed the gold certificates; he quit his job, yet still lived comfortably mere days after the ransom was paid; and, most damning of all, the sixteenth rail of the kidnapping ladder was made of wood pulled from Hauptmann’s attic, as revealed by the prosecution’s star witness, wood technologist Arthur Koehler.

Still, all of the evidence was circumstantial, and it only takes a little imagination to find ways the evidence could have been planted by co-conspirators, intrepid reporters, or even the investigators themselves.

But would they have?

The sad reality is, in the 1930s, it wouldn’t have been all that uncommon. Remember, though the Lindbergh case was called “The Trial of the Century,” it wasn’t the first to earn that moniker. Many controversial court cases dominated the headlines in the early part of the 20th century.

In 1907, the “Trial of the Century” was that of American Socialist labor leader Bill Haywood, who was charged as a conspirator in the murder of Frank Steunenberg in Idaho, despite being in Colorado at the time.

In 1921, the “Trial of the Century” centered around Italian immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, who despite tenuous evidence of their guilt and blatant examples of anti-immigrant prejudice, were sentenced to death by the state of Massachusetts.

And in 1931, the “Trial of the Century” took place in the Jim Crow South, as the nine Black teenagers known as “The Scottsboro Boys” stood trial in a court case so prejudiced and unjust that it served as the partial inspiration for both Richard Wright’s Native Son and Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird.

For the people who doubt Hauptmann’s guilt, there’s no clear consensus on the real identity of the Lindbergh Baby’s kidnapper/killer. Some believe Hauptmann was a co-conspirator in the kidnapping, but couldn’t have done it alone. Others believe he was a patsy, set-up by organized crime.

And then there’s the matter of Charles Lindbergh Sr. While the suggestion that a father would be involved in the death of their own child is beyond the pale, Lindbergh’s very public pronouncements on his belief in eugenics, as well as “superior races,” while having a son who was reportedly beset with a myriad of health issues and mild physical disabilities, has led some to speculate about the grimmest possible conclusion.

The only thing all parties agree upon—even some who fully believe in Hauptmann’s guilt— is that the convicted man failed to receive a fair trial.

Why Do We Still Care About the Lindbergh Baby?

The same year that Lindbergh-mania was sweeping the nation after his trans-Atlantic flight, aviation made history on the silver screen as well, when William A. Wellman’s Wings won the first ever Academy Award for Best Picture.

By 1943, Charles Lindbergh had resigned his colonel’s commission amidst a conflict with President Franklin D. Roosevelt due to Lindbergh’s suggestion that America negotiate a neutrality pact with Germany. Meanwhile, William A. Wellman was back at the Oscars, this time nominated for a Western film called The Ox-Bow Incident.

The movie tells the story of a cowboy who leads a posse to catch the killer of a local rancher. The posse comes across a trio of men, including a Mexican and a mentally disabled man, who happen to be spotted with some cattle belonging to the rancher. They claim to have bought them legally, but can’t produce proof. Despite the lack of evidence, the cowboy rallies the posse to lynch the men, only to return to town and discover that the rancher hadn’t actually been killed, and the men who had tried to kill him had been captured alive by the rancher. In a rush to seek righteous justice, innocent men died.

For most people, likely including the judge in New Jersey who recently ruled not to release the Lindbergh Baby evidence for DNA testing, Bruno Hauptmann is guilty, and the case is closed. Certainly, there’s plenty of circumstantial evidence to suggest as much. But those who want to dig further might not be doing so because they have some grand conspiracy theory to prove, nor because they think it will somehow restore Hauptmann’s legacy nearly a century later.

They just know that much of American history has been built on ox-bow incidents.

Michael Natale is the news editor for Best Products, covering a wide range of topics like gifting, lifestyle, pop culture, and more. He has covered pop culture and commerce professionally for over a decade. His past journalistic writing can be found on sites such as Yahoo! and Comic Book Resources, his podcast appearances can be found wherever you get your podcasts, and his fiction can’t be found anywhere, because it’s not particularly good.

Bettmann//Getty Images

Bettmann//Getty Images

The Kidnapping StoryNew York Daily News Archive//Getty Images

The Kidnapping StoryNew York Daily News Archive//Getty Images

How They Found Him

How They Found Him

LMPC//Getty Images

LMPC//Getty Images