The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine was arguably the most important engine of WW2. It had an ability to produce war-winning designs of almost anything it powered, including two of the most famous and beloved aircraft from the war; the P-51 Mustang and Spitfire. Not only this, but it was also used in tanks as the Meteor, which, for the first time, provided the British with a tank engine capable of delivering large amounts of power reliably.

Work started on what would become the Merlin in the early 1930s, after Rolls-Royce realised their successful 21 L 700 hp Kestrel V12 wouldn’t always be enough. Their next design, named the PV-12, would have a 27 L displacement and produce 1,100 hp. It was first fired up in 1933, and would first fly in a Hawker Hart in 1935. At the same time, the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane had been designed to accommodate the PV-12, and were the only aircraft at the time to do so.

With contracts for production of both these aircraft awarded in 1936, the Pv-12 was also given the green light for production. It would be named the Merlin, following Roll-Royce’s tradition of naming their engines after birds of prey.

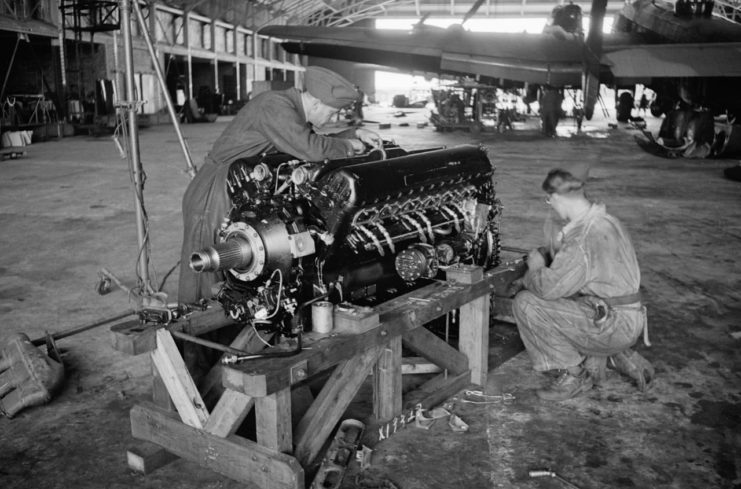

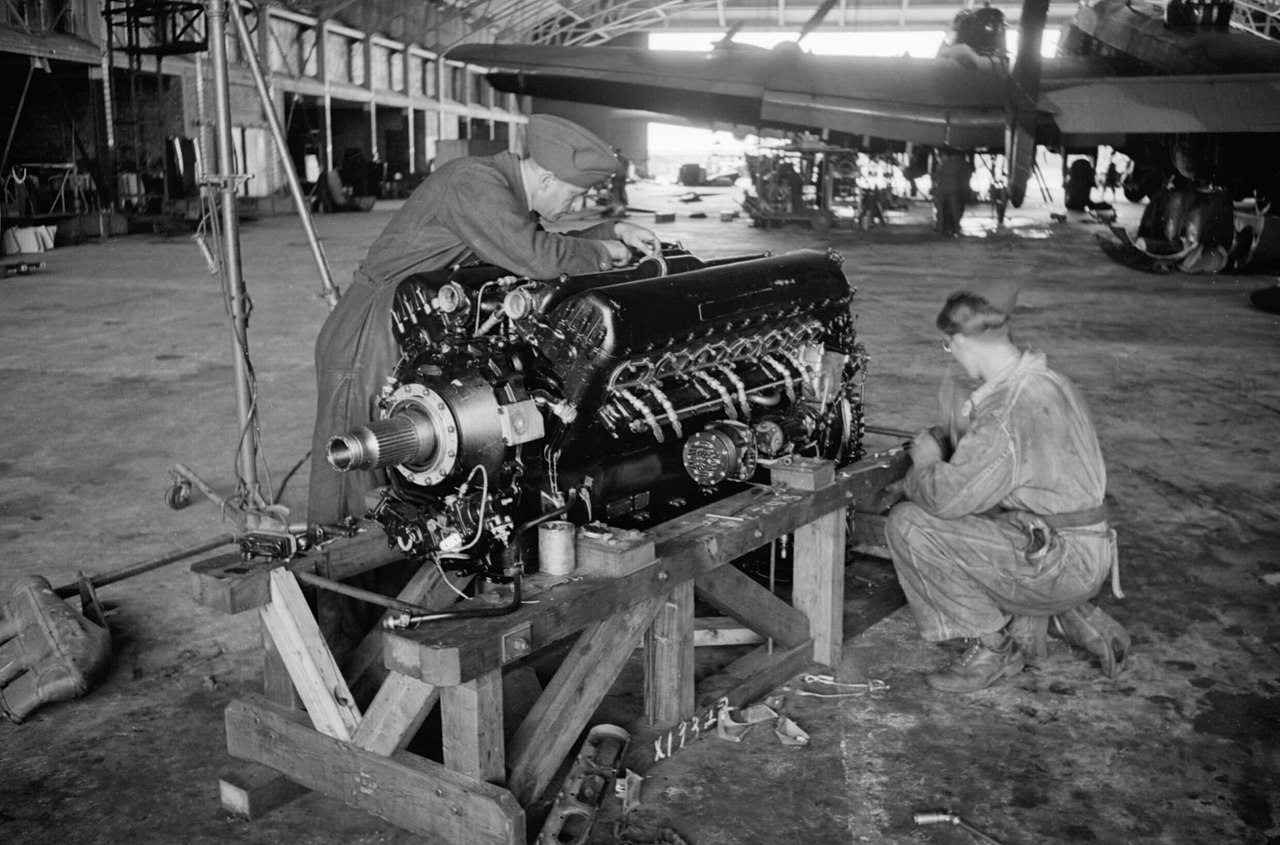

The Merlin I was the first variant to enter production, but over its life the Merlin would be made in over 50 versions.

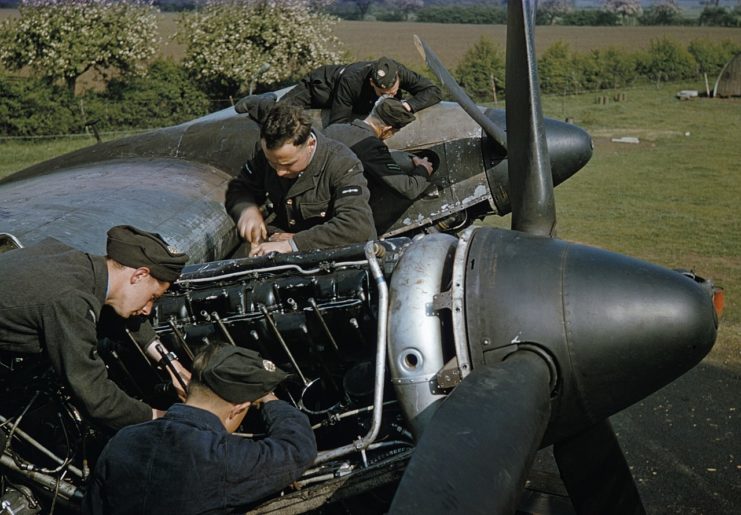

The Merlin saw great success in the dogfights over Europe, where its supercharger gave it a performance advantage at high altitudes over engines like the Allison V-1710. This supercharger was used on all models until the Merlin 60 series, when a two-stage supercharger was used. This gave an even bigger performance boost at high altitudes. The Merlin 60 could produce 300 more hp than the Merlin 45 at 30,000 ft, and gave the Spitfire IX a 70 mph speed increase over the Spitfire V.

One of the Merlin’s drawbacks however, was its carburetted air-fuel delivery. It was calculated that the lower temperature in the carburettor would provide a denser air and fuel mixture and therefore more power over a fuel injected system, but this came a cost of continuous fuel supply. If a Merlin powered aircraft nosed down into a steep dive, the negative g-forces would temporarily starve the engine of fuel and cut it off.

German aircraft like the Bf 109 were fuel injected, meaning they produced power at any orientation. They would often exploit this weakness in aircraft like the Spitfire by simply nosing down to avoid an attack.

This was partly solved with ‘Miss Shilling’s orifice’, named after its designer, which attempted to reduce the fuel rich mixture and maintain engine power. Further solutions were added, but the problem was never completely solved.

The Merlin could also be modified to produce a small amount of thrust to increase aircraft top speed with thrust. It consumed a vast amount of air (around the volume of a bus every minute), and would eject exhaust gases out at around 1,300 mph. It was discovered that if properly directed, this high speed air could produce a small amount of thrust equal to around 70 hp, adding 10 mph to a Spitfires top speed.

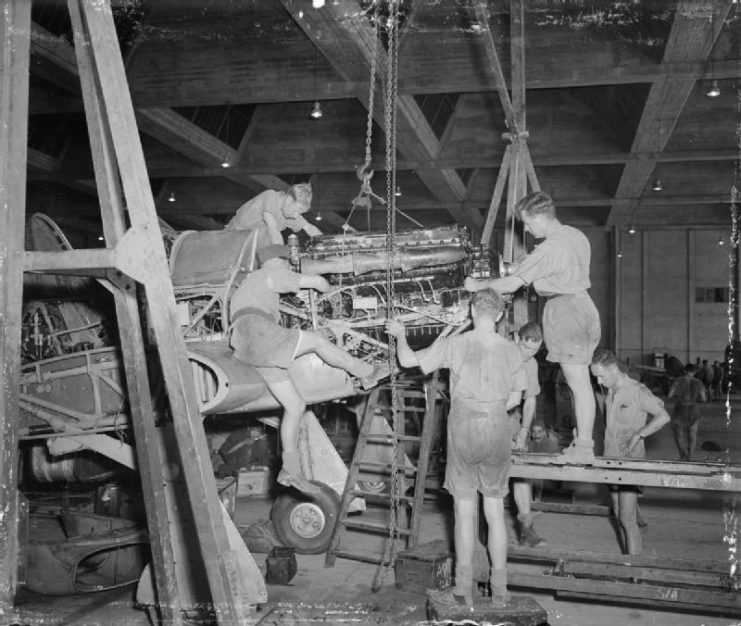

The P-51 Mustang also received some of the Merlin treatment in the P-51B. The Mustang was originally powered by the Allison V-1710, which performed well at low altitudes, but was severely outclassed by engines like the Merlin at high altitudes. With this engine, the P-51 became an entirely new beast, and made it one of the best aircraft of the war.

It also saw extensive use in the de Havilland Mosquito, which used two Merlins on its lightweight wooden frame. The Mosquito was also regarded as one of the best aircraft in the war, flying in almost every role imaginable. It also powered the Avro Lancaster bomber, which used four Merlins per aircraft.

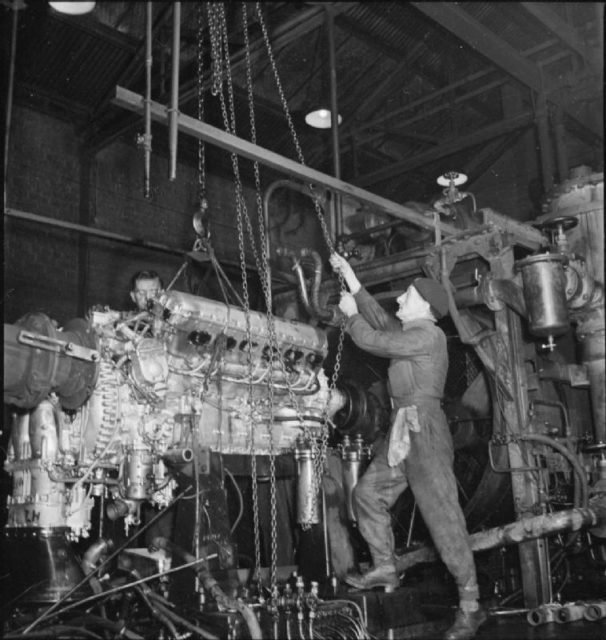

The Merlin was so desired that demand often outweighed supply. Despite this, around 150,000 were built in total. As British manufacturers couldn’t keep up with the amounts of engines needed, the engine design was licensed to Packard in the US, to aid production of the Merlin. This engine was known as the Packard V-1650 Merlin.

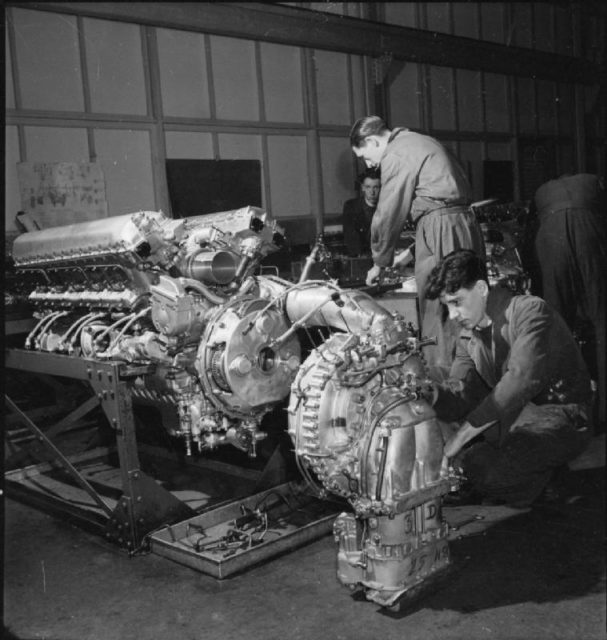

Slightly different to its aero-engine roots, the Merlin also saw use on the ground inside tanks. This was first trialled in a Crusader tank 1941, a time when the British were sorely lacking in reliable, powerful tank powerplants. The Merlin used had been recovered from a crashed aircraft and was no longer suitable for use in an aircraft, although still operational. It had aircraft-related components removed, like the supercharger and reduction gear. The Crusader is estimated to have reached an incredible 50 mph, proving the concept immediately.

As mentioned above, intense demand meant only Merlins taken from crashed aircraft could be used in tanks. In this role it would be known as the Meteor, and produced between 550-650 hp. The first production tank that used the Meteor was the Cromwell, a tank lacking in armor and firepower, but loved by its crews for its speed. It would eventually power the British Centurion, a tank that is today regarded as one, if not THE best tank ever built.