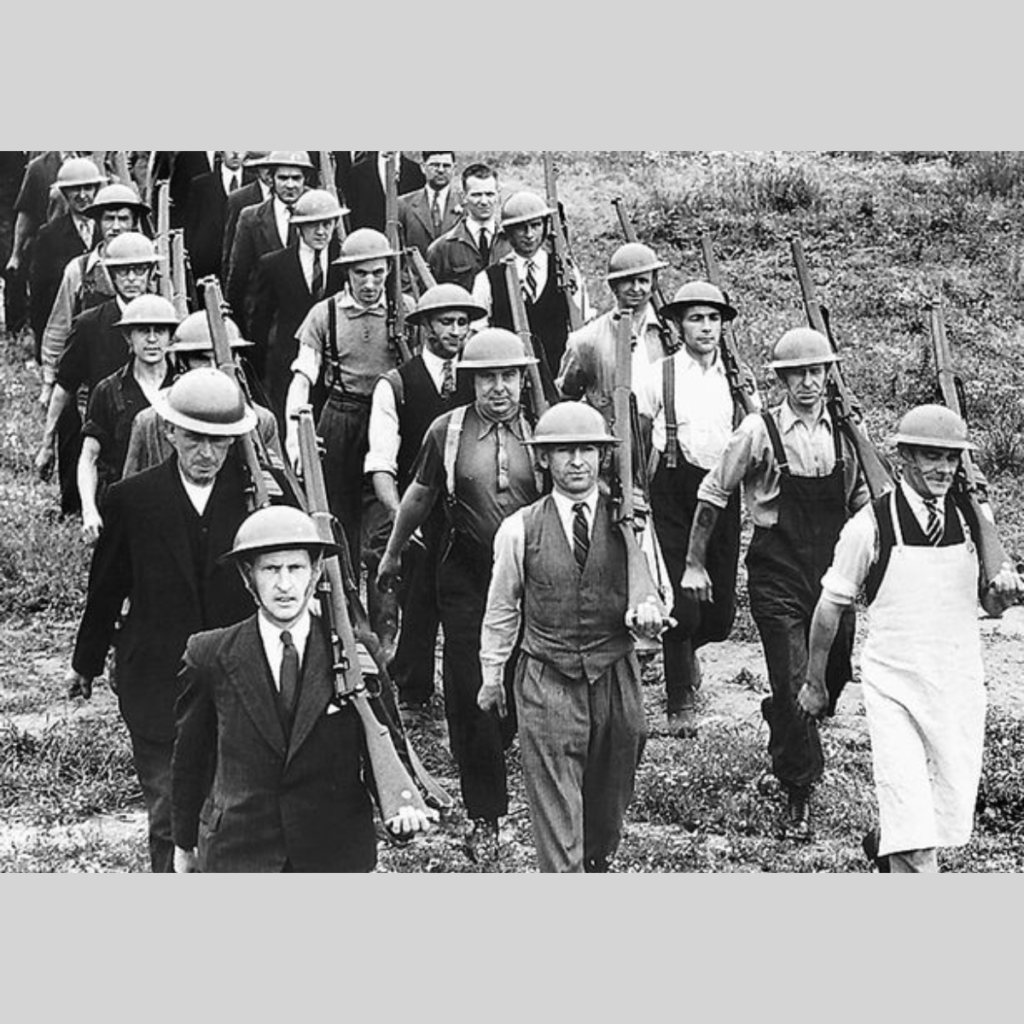

In May 1940 Britain stood in danger of her life. The Army in France was falling back before a massive German “blitzkieg” attack, their French allies had crumbled, panic was spreading throughout the Low Countries and at home the threat of invasion was poised at a level not exceeded since the days of the Napoleonic wars. It was against this background that Sir Anthony Eden, Secretary of State for War, broadcast to the nation an appeal for volunteers to come forward to form a defence force, organised on local basis, to supplement the Regular Army in defence of the homeland, especially against the new German tactic of the use of paratroops. The new force would be known as the Local Defence Volunteers, open to British subjects between the ages of fifteen (later altered to seventeen) and sixty-five, and initial enrolment would be at local police stations.

The announcement had barely been made before telephone enquiries were being received and volunteers were arriving on the doorstep to enroll by means of hastily prepared forms. Foremost among the enthusiasts was a local ex Army Major, of strong will and even stronger language, whose avowed intention towards the enemy was “to shoot the bastards”.

Arms were not officially available at that stage although soon a miscellany of shot guns, rook rifles and other assorted weaponry began to appear among the belligerent volunteers whose only uniform was an arm band bearing the letters LDV (Local Defence Volunteers). There was a limited issue of firearms to the police. The writer’s father received a revolver and a box of ammunition while a .303 rifle was also received into the station where it was warmly welcomed by a bushy moustached constable who was an ex regular soldier of First World War vintage. Even the local fire brigade had a Boer War rifle and three rounds of ammunition with which to defend their fire engine while the fire chief and a fireman appeared with pistols on their belts next to their axes. Britain was ready to fight.

The scenes were being repeated countrywide. At the base of organisations were the Lords Lieutenants and Secretaries of the Territorial Army Associations but initially arrangements were, by the very nature of things, very impromptu and haphazard. Paperwork thankfully was kept to a minimum, thoughts being centred more on the sword than the pen. Early instructions from the Adjutant General’s Office directed that the LDV’s were to be organised within existing Military Areas, divided into Zones and Groups and an unpaid Volunteer Organiser was to be put in charge of each Zone or Group. Area Commanders, in consultation with the Government’s Regional Commissioners, were to arrange the division of Areas and, in consultation with the Lords Lieutenants appoint the Volunteer Organisers of Areas, Groups and Zones. Initially many of the geographical divisions of Areas were made to coincide roughly with police divisions, there being no other immediately available local precedent. It also made police liaison easier. Although there were no official ranks as such, ex service officers came naturally to the fore in such circumstances.

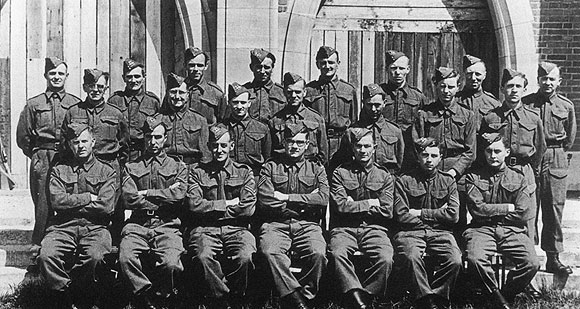

39 Platton 5th Battalion Surrey Home Guard.

For administration purposes reliance had to be placed on loans of premises and resources together with the help of volunteer workers. Such help was usually readily forthcoming in its various forms although in one office, where the girl typist was frantically typing LDV instructions, the dour Scotsman in charge was heard to comment, “if they (the LDV) canna supply the typist they might at least supply the paper”. Within a surprisingly short space of time arms were officially issued, principally to “front line” areas such as Kent, mainly in the form of rifles which, fresh from stores, were usually heavily greased and often “gritty”. Units, not yet in receipt of official arms, still relied on their unofficial collections including in one case a Ghurka knife. In one Lancashire mining village menacing figures armed with crowbars were to be found on patrol. Uniforms of khaki denim overalls began to be issued. All head dress seemed to be size 6½ irrespective of the heads they were supposed to fit.

As well as the “General Service” units, many factories and public and industrial organisations had their own formations. One such was Dennis Bros Platoon, 4th Guildford Home Guard. The commander was Major C T Skipper, a Company Director who, as an ex member of the First World War Royal Flying Corps, wore wings on his uniform. Railways had their own volunteers, those of the Southern Region being organised from Woking where the 12th Surrey (3rd Southern Railway) Battalion were based. Post Office units were mainly formed with a view to protecting communication centres against parachutists and saboteurs. The BBC were similarly organised and prepared.

Parnall’s Aircraft Factory at Yate, Gloucestershire, who were engaged in manufacturing aircraft gun turrets during the war, had their own detachment of volunteers. Enthusiastically, they acquired two old turrets and machine guns of an obsolescent nature, together with ammunition, and mounted them on the roof as a defence against air attack. Sadly this was not to prove sufficient deterrent later in the war when the factory was demolished and set on fire and fifty-two people were killed during a daylight air raid by a single enemy aircraft. Captured German papers after the war, however, showed an aircrew member recording that the aircraft had been hit by gunfire (of indeterminate origin) during the raid. Night patrols and road blocks and checks were regularly mounted by General Service Units. Regretfully on some occasions understandable over-reactions by armed members caused casualties. A special Constable of the Gloucestershire Constabulary was fatally shot by Home Guard members when travelling to his police station in his car in the Forest of Dean at night. An inquest jury returned a verdict of “justifiable homicide”. Some members on patrols apparently allowed their attention to wander on occasions. In Yorkshire a volunteer was severely reprimanded “for rabbiting in the early morning when he should have been on lookout”.

In July 1940 the rather cumbersome title of Local Defence Volunteers was changed to the more prestigious one of Home Guard. Command structures, with appropriate badges of rank, were formulated and later officers, properly commissioned, were appointed. As the winter of 1940-41 developed the immediate danger of invasion receded but there was no lack of duty or tasks for the Home Guard who during the time of the blitz became heavily involved in air raid duties. They participated in all activities carrying out guards, assisting in rescue work and fire fighting or rendering first aid and removing casualties. All this had to be combined with their normal employment. All those with arms were most anxious to bring down an enemy aircraft and there were claims of having done so. But for the 3rd Renfrewshire Battalion there was an unexpected “drop” from the sky when Rudolf Hess landed by parachute from his abandoned aeroplane and was arrested by local volunteers.

A Home Guard platoon.

The County of Surrey was quick to respond to the call in 1940. The first elements of the Volunteers were formed at Camberley and Farnham where the police stations were besieged by men of all ages from all walks of life who were eager to enrol. Other areas showed similar determined attitudes with the result that formations were quickly effected and affiliated to the two County Regular Army Regiments of The Queen’s and Surrey’s as shown below:-

The Queen’s Royal Regiment

| Home Guard Battalion | Raised | Based | Remarks |

| 1st Surrey Battalion | May 1940 | Camberley and Farnham | |

| 2nd Surrey Battalion | Summer 1940 | ||

| 4th Surrey Battalion | May 1940 | Guildford | |

| 5th Surrey Battalion | Godalming and country districts | ||

| 11th Surrey Battalion | 1942 | Woking and Chobham | |

| 12th Surrey Battalion | Southern Railway Unit with HQ at Woking | ||

| 23rd Surrey Battalion | June 1940 | Croydon |

In addition, the following Home Guard battalions of which there are no records were also affiliated to The Queen’s: 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 32nd and 60th. The following Home Guard battalions were affiliated to The East Surrey Regiment:

The East Surrey Regiment

| Home Guard Battalion | Raised | Based | Remarks |

| 3rd Surrey Battalion | Weybridge | ||

| 51st Surrey Battalion | 1940 | Malden | |

| 56th Surrey Battalion | May 1940 | Epsom and Ewell | |

| July 1940 | Amalgamated with Banstead | ||

| 62nd Surrey Battalion | July 1940 | Norbury |

| Home Guard Battalion | Raised | Based on | Remarks |

| 1st Surrey | May 1940 | Camberley and Farnham | A 2nd Bn. formed soon afterwards |

| Autumn 1940 | Woking & Chobham | Farnham companies to another battalion | |

| October 1942 | Sunningdale , Normandy and Worplesdon | ||

| 4th Surrey | May 1940 | Guildford | In close liaison with ITC at Stoughton Barracks |

| 5th Surrey | Effingham, ShereCranleigh and Chiddingfold | Godalming and Haslemere to another battalion | |

| Feb 1942 | Bramley | ||

| 11th Surrey | 1942 | Woking and Chobham | Formed from 1st Battalion |

| 12th Surrey (3rd Southern Railway) | Woking | Covered over 100 stations of the Southern Railway | |

| 33rd Surrey | June 1940 | Croydon | Personnel from the staff of Croydon Corporation. |

| 51st Surrey | June 1940 | Malden | Commando Company formed in April 1941. Medical Section formed in Summer 1941 |

| 56th Surrey | May 1940 | Epsom and Banstead | Amalgamated with Ewell in July 1940. |

| 62nd Surrey | July 1940 | Norbury | |

| 63rd Surrey | 1940 | Richmond | |

| 64th Surrey | May 1944 | Kingston | Formed from personnel transferred from 53rd Surrey (Molesey) Bn. |

Guarding of vulnerable points had to be quickly organised. Surprisingly, consideration was given to the matter of the Milk Marketing Board building then under construction. By the 27th May some rifles were being received so the bands of hastily mustered volunteers were beginning to shape into an organised Armed Force. Until they received an official issue of firearms the Molesey group made use of borrowed miniature weapons and practised on the Metropolitan Police range at Imber Court. The Kingston Group, on becoming possessed of .303 rifles underwent training at the Depot of The East Surrey Regiment and later at Bisley.

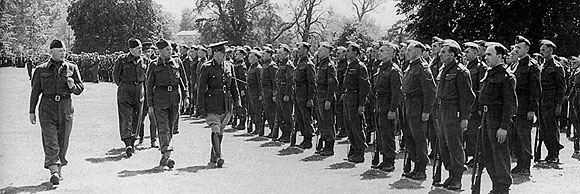

A Home Guard platoon in front of Guildford Catheral

Generally speaking the Surrey volunteers were blessed with the proximity of Regular Army establishments which greatly facilitated training. Lieutenant Colonel J L B Vesey, commanding the 1st Battalion of the Surrey Home Guard was very appreciative of the support he received from the Aldershot District. The 4th Battalion at Guildford were in close liaison with the ITC at Stoughton Barracks.

Courage was certainly not lacking in the County. In connection with supporting Civil Defence activities during air raids the 33rd (County Borough of Croydon) Battalion gained one George Cross and four George Medals, three British Empire Medals and four commendations. Regretfully, two members lost their lives due to enemy action. There was ample support from the public for the Home Guard. When ‘C’ Company, 8th (Reigate) Battalion were on duty at the “Black Horse” road block, their commander was approached by a gentleman who wished to show his interest by presenting a cup and medals for competition by teams of men at the Miniature Ranges. The offer was officially approved and accepted.

The 51st (Malden) Battalion was able to take the war to the enemy in more active form when they took part in rounding up German air crew who sometimes baled out over their area. Tragically, on their own side they lost five killed and seven wounded by enemy action. Improvement in the supply of weapons resulted in the formation of a Special Service Platoon under Lieutenant Hepburn who was recognised as an expert in machine guns.

When dwelling on the efforts of men in the various battalions, tribute should also be paid to the women supporters, often wives, girl friends and relatives of the Volunteers. Although not officially part of the Force they contributed in many ways in matters of administration, communication, catering and medical services. The 51st Battalion in fact formed a complete Medical Section composed of both men and women. Supplies were either purchased or made privately.

The Guildford Battalion Surrey Home Guard – Salford. Commanded by Colonel Guy Westland Geddes, who had returned to Guildford in 1954 after 34 years of military service.

The 56th (Epsom and Banstead) Battalion, with obvious appreciation of their specific location, made use of the facilities of the Race Course and during the summer of 1941 a week-end training school was formed at the Grand Stand. Attended by representatives from all Battalions in SW London Sub Area, it was formally opened by the GOC London District who was accompanied by Major Atlee.

The 62nd (Norbury) Battalion had an overwhelming response by volunteers on formation, so much so that they had to increase their original waiting list of 300, but by 1941 their numbers were becoming depleted by drafting of men to the Armed Forces, so they organised a recruiting drive which included a march headed by the band of The Scots Guards accompanied by other military bands, Bren-gun carriers and artillery. The salute was taken outside Norbury police station by Brigadier General Whitehead, commanding the London Area.)

Few units could have had such a beautiful and historic area to defend as the 63rd (Richmond) Battalion whose territory included Kew Gardens and Wick House, once the residence of Sir Joshua Reynolds. But there were other things than beauty to think about. Enemy air attacks were frequent and on one night in 1940 Richmond, illuminated by flares, became the specific target. Valuable assistance was rendered to the Civil Defence services and Pte Dean was commended for his bravery. He later became an officer in the Regular Army.

In May 1943, on the occasion of the Home Guard’s third birthday, special parades were held throughout the country. At Addlestone the 10th (Chertsey and Egham) Battalion gave displays of bayonet fighting, camouflage and first aid at Victoria Park. In 1944 the Home Guard, their duty done, were stood down. Farewell parades were held, that of the 11th (Woking) Battalion taking place on the Wheatsheaf Recreation Ground, Horsell where 747 officers and men paraded to be addressed by the Commanding Officer, General Sir Alan Bourne.

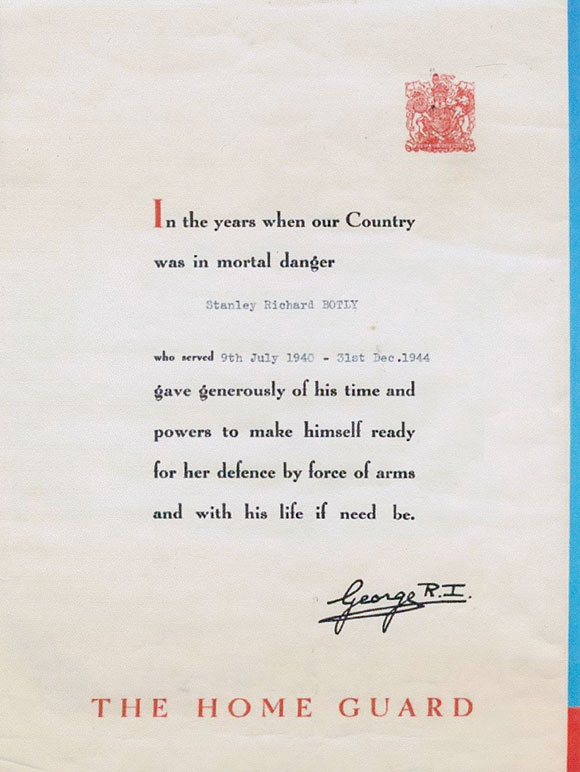

As the war progressed the Home Guard became more and more professionally trained, armed and equipped and developed into an efficient fighting force. By 1943 they were even manning anti-aircraft batteries in some places. They became subject to military law although Commanding Officers were reluctant to resort to such measures. In Cheshire, however, two privates were given fifty-six days for insubordinate language to their superior officer. They served only a week before the sentence was suspended. Gradually the country progressed from a defensive state and attitude to an offensive one. In 1944 as preparations were made, and eventually activated, for the invasion of Europe there was the danger that the enemy may launch counter-measures against Britain. Security measures had to be undertaken and during the “mini-blitz” era of the flying bombs renewed air raid activities were necessary. But eventually the longed for day of Victory arrived and the Home Guard were able proudly to take part in the resulting celebrations and processions, knowing full well that they had nobly partaken in the defence of their country and contributed to its triumph in arms. Members received a certificate which, by way of signature of King George VI, paid tribute to the fact that “when our country was in mortal danger….. they were ready for her defence by force of arms and (sacrifice) of life if need be”.

Home Guard Certificate.

In 1952 the Home Guard was reconstituted as part of the Armed of the Crown, and the following twelve Surrey Home Guard battalions were affiliated to The Queen’s Royal and East Surrey Regiments: 3rd, 6th, 10th, 51st, 52nd, 53rd, 54th, 55th, 56th, 57th, 63rd, and 64th. But the new effort was not particularly distinguished or long lasting. Many felt no doubt that the old days of the Home Guard and its volunteer fighting spirit had passed away with the 1940s. But one thing had not gone and never will – the memory of an era when England’s menfolk, with the support of their women, rallied to the call to arms to defend their country in its hour of need.