Approximately 20 miles off the coast of Washington, the SS Pacific steamship sank on November 5, 1875. The vessel plummeted into the Pacific Ocean’s depths, taking hundreds of lives and millions in gold.

The exact location of the wreck is still a closely kept secret.

Recently, two men, Matt McCauley and Jeff Hummel, claim to have found the remains of the SS Pacific. They plan to salvage and display its artifacts in a proposed museum. Moreover, they will present their research, findings, and plans during a talk at the Foss Waterway Seaport in Tacoma.

The last journey of SS Pacific started from Victoria, B.C., San Francisco. Unfortunately, the steamship sank with at least 325 passengers and crew. Only two survived the wreck.

McCauley and Hummel own the non-profit organization, the Northwest Shipwreck Alliance. They found the shipwreck through their organization.

The two, both 58, began salvaging underwater wreckage while they were still in high school.

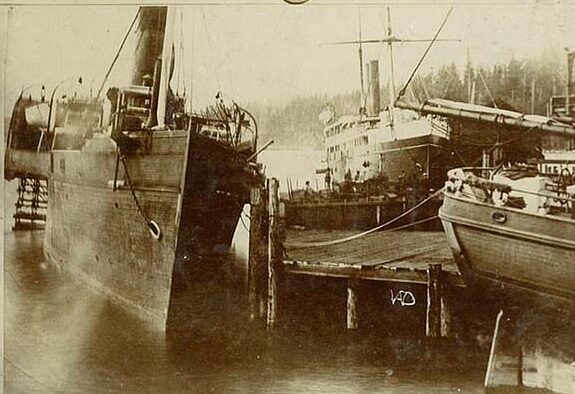

SS Pacific

The SS Pacific launched in 1850 in New York. It was a 225-foot long and cost an estimated $100,000. The ship was steam-powered and had two side wheels that gave propulsion.

The ship has a history that’s worth telling. It carried both passengers and cargo. The boat also set a speed record on its inaugural run. Soon after this, New York business magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt bought the vessel.

Before the construction of the Panama Canal, the steamship served the Chagres (Panama)-New Orleans and Nicaragua-San Francisco routes.

The sinking was not the first tragedy that hit the ship however. In 1855, 45 passengers died from cholera picked up while transiting across Nicaragua. Moreover, in 1861, strong winds pushed it off its course and caused it to sink in the Columbia River. The area is specifically famous for numerous shipwrecks, which earned it the name of the ship graveyard.

However, the owner raised the ship following the sinking and brought it back to service. Finally, in 1875, the ship was bought by its final owner and put on the Puget Sound-San Francisco run.

The Shipwreck

The steamship left from Tacoma on November 3, 1875, for Seattle to eventually stop at Victoria on November 4. According to McCauley, the ship was under the captainship of Jeff Howell, a famous skipper in Tacoma.

“He was somebody that everyone liked at every port at which the vessel stopped, so (his death) was a big blow to the folks in Tacoma,” McCauley explained.

Several miners from the northern gold fields boarded the ship at Victoria. The boat carried millions of dollars in gold coins, bars, and dust. Initially, in 1849, William H. Brown designed the ship for the California Gold Rush, giving it a robust and safe room.

After boarding, the ship set out for the ocean through the Strait of Juan de Fuca and turned south about 12 miles off Cape Flattery. All the while, the ship’s captain was below deck analysing maps. The clipper SV Orpheus was headed north. The crew did spot its masthead but mistook it for Cape Flattery lighthouse.

Without warning, the Orpheus turned in front of the Pacific.

The ships collided with one another. Pacific’s bow struck the hull of the Orpheus in three places. The Orpheus sustained minimal damage and continued on its path. The Pacific went on its way, unaware of what was coming its way.

The Tragedy: 325 Lost to the Sea

Neil Henly, 21, the Pacific’s quartermaster and one of the two survivors, explained: “I woke up with the crash. I jumped out of my bunk, the water rushing through the bow, and saw all hands rush on the hurricane deck. The ship fell into the sea trough and became unmanageable, the fires being extinguished; all was confusion, the passengers crowding into the boats the officers and crew were trying to clear away.”

Remarkably the crew filled the lifeboats with water to keep the ship on an even keel, adding to the sinking.

Passenger Henry Jelly, 22, the ship’s other survivor, recalled, “The boat I was near was partly full of water. It was about an hour from when the steamer struck up to when she listened to port so much that the port boat was let into the water and cut loose from the davits.”

The lifeboat capsized.

“I crawled up on the bottom of the boat and helped several others up with me … I think about all the ladies in our boat, and when they got upset, they all fell into the water and, I fear, they were all drowned,” Jelly later said.

Jelly survived the wreck by lashing himself onto the wreckage of the pilot house. Passing ships picked up Jelly the next day and Henly the day after.

The SS Pacific became the worst maritime disaster on the West Coast, with 325 lives lost. Hummel anticipates that the total number of lives lost was approximately 500, mainly from illegally onboard passengers.

Washington Territory

When the steamship sank, Washington was still a decade away from being a state. “This was a massive tragedy when you consider the relatively low population of BC and the Washington territory at that time,” McCauley explained.

“It was a significant vessel for Tacoma, as it was bound for Seattle and some of the area waypoints on the Sound.”

The 1870s witnessed important developments in Tacoma. In 1873, the Northern Pacific Railroad chose the city as its western trans-continental terminus. They built their headquarters there in early 1875.

“But it was still essential that it had the steamboat connection with San Francisco, which was the civilized world to the people in Washington Territory at that time. Seattle had a population of under 2,000 residents at that time, and Tacoma’s was even smaller.” McCauley explained.

The city was incorporated as a state on November 12, 1875—only a week after the SS Pacific wreckage.

But is it really the SS Pacific?

McCauley and Hummel were not the first to look for SS Pacific. Several expeditions, starting in 1885, attempted to find the boat’s wreck. Yet, surprisingly, all of them failed.

Hummel’s salvage company, Rockfish, Inc., calculated the wreck’s location using the information: heading, speed, currents, and timing. The report led to a search of 338 square miles, a vast area.

One of the most critical clues came from commercial fishermen. Several of them caught chunks of coal in their nets. These chunks were tested and identified as the coal from the ship’s last owners, Goodall, Nelson, and Perkins.

The discovery narrowed the search to two square miles.

Rockfish used various underwater equipment to search for the wreck for five years. Finally, in 2021, the ship was spotted for the first time using sonar imaging.

Imaging machinery found a hull-like depression and two nearby circular depressions, likely from the ship and its paddle wheels. The wooden wheels remain intact under the seafloor mud.

Hummel explained, “If you look at the preponderance of the evidence, it’s overwhelming. The odds that it’s not the Pacific are one in a million.”

Finders Keepers

The imaging showed promising evidence, leading the salvagers to file legal rights in the US District Court for the square miles. As a result, US District Court Judge James L. Robart issued an order that restricts competing salvagers from invading the area.

The team remains silent on the specifics.

“There are two things we never tell people,” Hummel said. “One is exactly how far from shore it is and exactly how deep it is.”

Hummel did offer an estimated range of 20-27 miles from shore and between 1,000 and 2,000 feet in depth.

The search continues.