Built from wood because of wartime restrictions on the use of aluminum and concerns about weight, the aircraft was nicknamed the Spruce Goose by critics, although it was made almost entirely of birch.

The largest wooden airplane ever constructed and flown only one time, the H-4 Hercules (nicknamed Spruce Goose) represents one of humanity’s greatest attempts to conquer the skies.

It was born out of a need to move troops and material across the Atlantic Ocean, wherein in 1942, German submarines were sinking hundreds of Allied ships.

Henry Kaiser, the steel magnate, and shipbuilder conceived the idea of a massive flying transport and turned to Howard Hughes to design and build it.

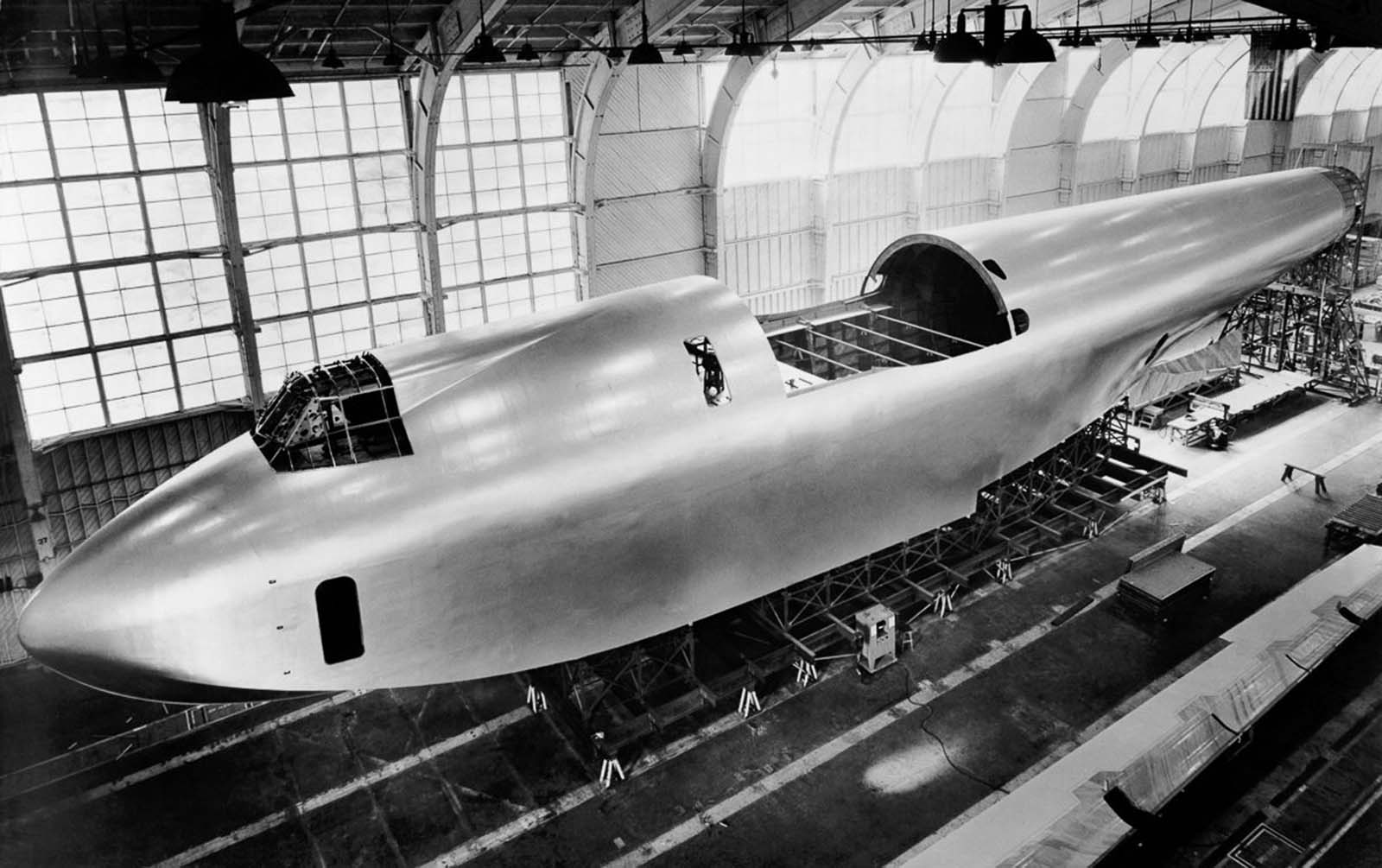

Hughes took on the task, made even more challenging by the government’s restrictions on materials critical to the war effort, such as steel and aluminum. Six times larger than any aircraft of its time, the Spruce Goose, also known as the Hughes Flying Boat, is made entirely of wood.

The final design chosen was a behemoth, eclipsing any large transport then built.

The plane would need to carry 150,000 pounds, 750 troops, or two 30-ton Sherman tanks. Originally designated the HK-1, the seaplane Hughes designed was absolutely massive. Weighing in at 300,000 pounds, with a wingspan of 320 feet, the plane was the largest flying machine ever built.

Originally designated HK-1 for the first aircraft built by Hughes-Kaiser, the giant was re-designated H-4 when Henry Kaiser withdrew from the project in 1944. Nevertheless, the press insisted on calling it the “Spruce Goose” despite the fact that the plane is made almost entirely of birch.

Hughes hated the nickname. He felt it was an insult to the prowess of his engineers. The construction of the plane dragged on, partly because of Hughes’s notorious perfectionism, and the war ended before the behemoth could be completed. After Kaiser dropped out of the project, Hughes renamed it the “H-4 Hercules.”

he Hercules is the largest flying boat ever built, and it had the largest wingspan of any aircraft that had ever flown until the Scaled Composites Stratolaunch first flew on April 13, 2019.

The plane had a single hull, eight radial engines, a single vertical tail, fixed wingtip floats, and full cantilever wing and tail surfaces. The entire airframe and surface structures were composed of laminated wood and all primary control surfaces, except the flaps, were fabric covered.

The aircraft’s hull included a flight deck for the operating crew and large cargo hold. A circular stairway connected the two compartments. Fuel bays, divided by watertight bulkheads, were below the cargo hold.

By 1947, the U.S. government had spent $22 million on the H-4 and Hughes had spent $18 million of his own money. The winged giant made only one flight on November 2, 1947. The unannounced decision to fly was made by Hughes during a taxi test.

With Hughes at the controls, David Grant as co-pilot, and several engineers, crewmen, and journalists on board, the Spruce Goose flew just over one mile (1.6 km) at an altitude of 70 feet (21 meters) for one minute and at a speed of 80 mph (128 km/h). The short hop proved to skeptics that the gigantic machine could fly.

Perhaps always dreaming of a second flight, Hughes retained a full crew to maintain the mammoth plane in a climate-controlled hangar up until his death in 1976.

The Spruce Goose was kept out of the public eye for 33 years. After Hughes’ death in 1976, it was gifted by Hughes’ Summa Corporation to the Aero Club of Southern California. The Aero Club then leased it to the Wrather Corporation, and moved it into a domed hangar in Long Beach, California.

In 1988, The Walt Disney Co. acquired the location, and Disney’s plans for the site did not include the “Spruce Goose.” Facing the loss of its lease, the Aero Club sold the giant plane to the Evergreen Aviation Museum (now the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum) in 1993, which disassembled the aircraft and moved it by barge to its current home in McMinnville, Ore.

Howard Hughes inside the “Spruce Goose.” 1947.

The “Spruce Goose” is transported from Culver City to Long Beach, California. 1946.

It would be built mostly of wood to conserve metal (its elevators and rudder were fabric-covered), and was nicknamed the Spruce Goose (a name Hughes disliked) or the Flying Lumberyard.

The huge wings being transported. 1946.

It is over five stories tall with a wingspan longer than a football field. That’s more than a city block.

In all, development cost for the plane reached $23 million (equivalent to more than $283 million in 2016).

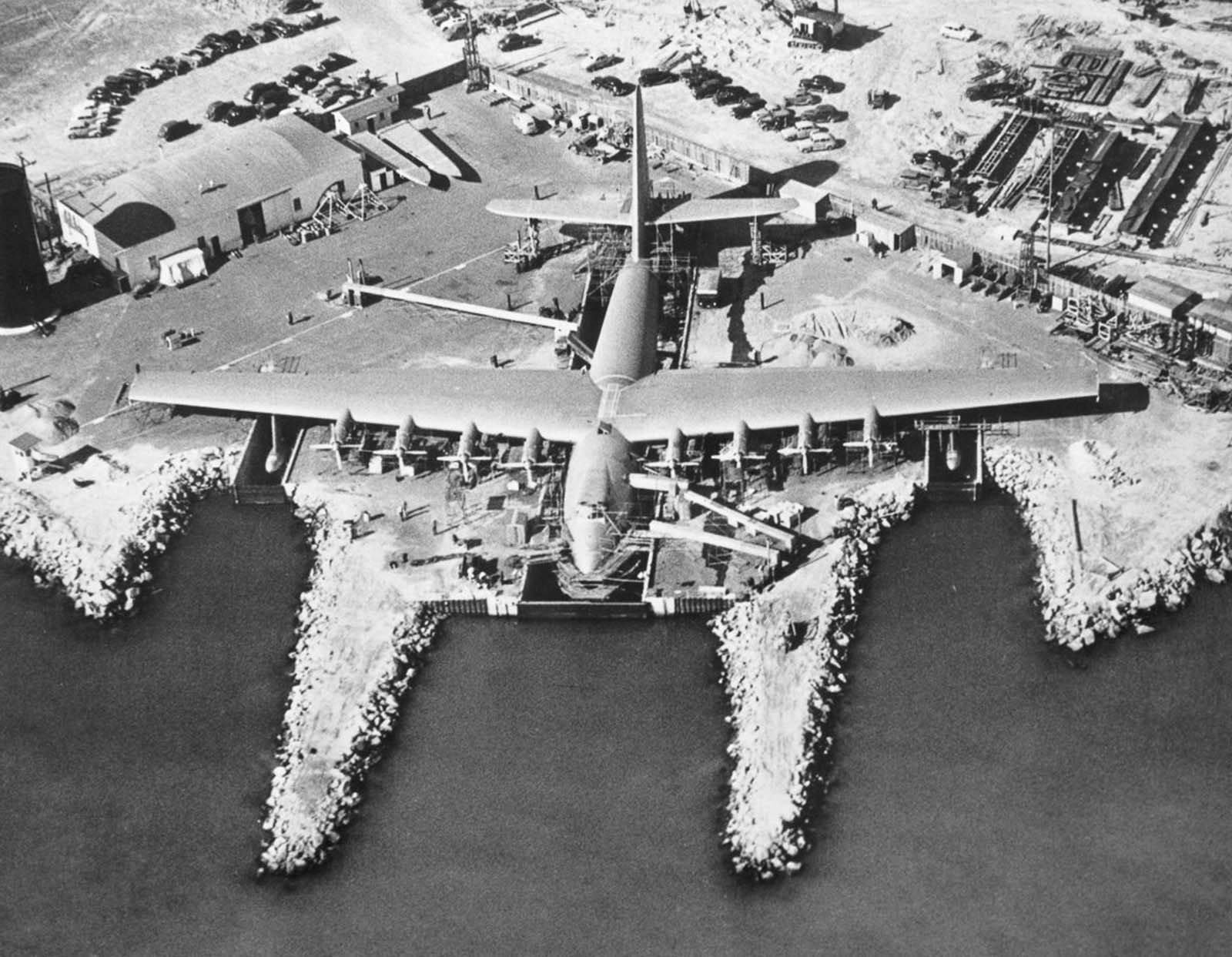

A house moving company transported the airplane on streets to Pier E in Long Beach, California. They moved it in three large sections: the fuselage, each wing—and a fourth, smaller shipment with tail assembly parts and other smaller assemblies.

The plane was built by the Hughes Aircraft Company at Hughes Airport, location of present-day Playa Vista, Los Angeles, California, employing the plywood-and-resin “Duramold” process – a form of composite technology – for the laminated wood construction, which was considered a technological tour de force.

The “Spruce Goose” under construction in its graving dock in Los Angeles Harbor. 1947.

Hughes in the cockpit.

Hughes prepares to take the “Spruce Goose” out for tests. 1947.

On November 2, 1947, the taxi tests began with Hughes at the controls. His crew included Dave Grant as copilot, two flight engineers, Don Smith and Joe Petrali, 16 mechanics, and two other flight crew.

The H-4 also carried seven invited guests from the press corps and an additional seven industry representatives. In total, thirty-six people were on board.

After picking up speed on the channel facing Cabrillo Beach the Hercules lifted off, remaining airborne for 26 seconds at 70 ft (21 m) off the water at a speed of 135 miles per hour (217 km/h) for about one mile (1.6 km).

The “Spruce Goose” flies for the first and only time. Nevertheless, the brief flight proved to detractors that Hughes’ (now unneeded) masterpiece was flight-worthy—thus vindicating the use of government funds.