The man who would construct American armored units in France in World War I and lead combined arms units, with armor at the forefront, in World War II got his start leading cavalrymen and cars in Mexico. In fact, he probably led the first American motor-vehicle attack.

Pancho Villa, 5, Gen. John J. Pershing, 7, and Lt. George S. Patton Jr., 8, at a border conference in Texas in 1914.

(Public domain)

The boy who would be Gen. George S. Patton Jr. was born into wealth and privilege in California, but he was a rough-and-ready youth who wanted to be like his grandfather and great-uncle who had fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War.

He attended West Point, became an Army officer, designed a saber for enlisted cavalrymen, and pursued battlefield command. When Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing was sent to Mexico to capture raiders under Pancho Villa, Patton came along.

Patton was on staff, so his chances of frontline service were a bit limited in the short term. But he made his own opportunities. And in Mexico, he did so in May 1916.

U.S. Army soldiers on the Punitive Expedition in 1916.

(U.S. Department of Defense)

Patton led a foraging expedition of about a dozen men in three Dodge Touring Cars. Their job was just to buy food for the American soldiers, but one of the interpreters, himself a former bandit, recognized a man at one of the stops. Patton knew that a senior member of Villa’s gang was supposed to be hiding nearby, and so he began a search of nearby farms.

At San Miguelito, the men noticed someone running inside a home and Patton ordered six to cover the front of the house and sent two against the southern wall. Three riders tried to escape, and they rode right at Patton who shot two of their horses as the third attempted to flee. Several soldiers took shots at him and managed to knock him off his horse.

That third rider was Julio Gardenas, a senior leader of Pancho Villa’s gang. The first two riders were dead, and Gardenas was killed when he feigned surrender and then reached for his pistol. Patton ordered a withdrawal when the Americans spotted a large group of riders headed to the farm. They strapped the bodies to the hoods of the cars and went back to camp.

An Associated Press report from the 1916 engagement. Historians are fairly certain that this initial report got the date and total number of U.S. participants wrong, believing the engagement actually took place on May 14 and involved 10 Americans.

(Newspapers.com, public domain)

It was a small, short engagement, but it boded well for the young cavalry officer. He had made a name for himself with Pershing, America’s greatest military mind at the time. He had also gotten into newspapers across the U.S. He was his typical, brash self when he wrote to his wife about the incident:

You are probably wondering if my conscience hurts me for killing a man [at home in front of his family]. It does not.

Patton’s bold leadership in Mexico set the stage for even greater responsibility a few short years later.

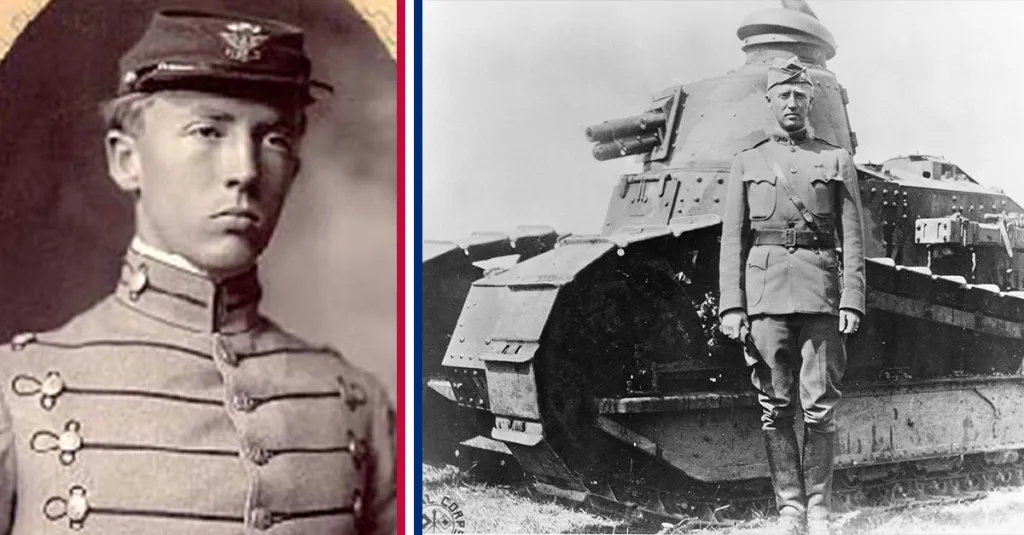

Lt. col. George S. Patton Jr., standing in front of a French Renault tank in the summer of 1918, just two years after he led a motor-vehicle charge in Mexico against bandits.

(U.S. Army Signal Corps)

When America joined World War I, Pershing was placed in command of the American Expeditionary Force.

Patton, interested in France and Britain’s new tanks, wrote a letter to Pershing asking to have his name considered for a slot if America stood up its own tank corps. He pointed out that he had cavalry experience, experience leading machine gunners, and, you know, was the only American officer known to have led a motorized car attack.

Pershing agreed, and on Nov. 10, 1917, Patton became the first American soldier assigned to tank warfare. He stood up the light tank school for the AEF and eventually led America’s first tank units into combat.