If Hollywood ever gets around to making a movie about “Scrappy” Blumer, the plot won’t need any embellishment. In fact, scriptwriters might have to tone down Blumer’s extraordinary achievements and full-throttle shenanigans during World War II to make them appear more believable. But such is the true-life story of a tougher-than-a-coffin-nail fighter pilot who came to be known as “The Fastest Ace in the West.”

Laurence Elroy Blumer was born May 31, 1917, to Paul and Geoline Blumer in Walcott, North Dakota. Like many immigrants who settled in the area, his maternal ancestors hailed from Norway, and undoubtedly passed down an adventurous Viking spirit to young Larry (his first of many nicknames). Growing up in the rural Midwest, he learned to hunt and fish while developing sharp hand-eye coordination that would later serve him well 5,000 miles from home. He was a student at Kindred High School (naturally, the “Vikings”), where he excelled in basketball and track. After graduating in 1936, he spent a couple of years working in carpentry and construction before enrolling at Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota.

America’s entry into World War II saw the Blumers relocate to the Pacific Northwest, where Paul found work at a munitions plant in Puyallup, Washington. Meanwhile, Larry enlisted in the Army Air Corps in March 1942 and learned to fly at Mira Loma in Oxnard, California. Next, he earned his wings at Luke Field, near Phoenix, and then reported to Marysville Cantonment, a large military garrison in Yuba County in northern California. Although his time there was brief, the repercussions would last a lifetime.

Blumer posted to the 393rd Squadron of the 367th Fighter Group, an assignment that punched his ticket to the European Theater of Operations and an eventual showdown with the Luftwaffe. But before shipping off to Europe, he received an indelible nickname befitting his fiery demeanor. As the story goes, he had been at a party on the base when he got into a fight with several Marines. The next morning, his commanding officer, who had witnessed the brawl, summoned the North Dakotan to his office. But instead of reprimanding him, the C.O. praised Blumer for holding his own against two of the Marines in the dustup, thus forever branding him “Scrappy.”

The 367th FG had three squadrons—the 392nd, 393rd, and 394th—and they trained in Bell P-39D Airacobras at bases in the San Francisco Bay area. Additionally, they had bombing and gunnery instruction in Tonopah, Nevada, where Blumer decided to expand target practice to the nearby town of Mina. “We were taking a bead on everything—it didn’t make no difference,” Blumer recalled. “I was about 20 feet off the ground coming through town, pulled the trigger, and had about seven shells left. Right through the water tower!” After hightailing it back to the base, he grabbed a bucket of paint and altered the nose and tail of his airplane to cover his tracks.

As the war dragged on, it created an increasing demand for replacement pilots, including those of the 367th.

The group finally departed for Europe from New York Harbor on March 26, 1944, for an 11-day convoy to Britain. The 367th shipped aboard the transport ship SS Duchess of Bedford, a former Canadian Pacific liner drafted into wartime service and dubbed the “Drunken Duchess” for the way it wallowed through heavy seas. The fighter group, now under Lieutenant Colonel Charles M. Young, eventually arrived at USAAF Station AAF-452 on England’s southern coast. The build-up for the D-Day invasion of Normandy was in full swing and security prevented the pilots from providing people back home with the base’s geographical location at a place called Stoney Cross. Once they arrived, the pilots, having trained exclusively on single-engine airplanes, expected to find North American P-51 Mustangs waiting for them. Instead, they were greeted by rows of twin-engine Lockheed P-38 Lightnings. The curveball required several weeks of training and familiarization before the men could finally take a whack at the enemy in their new airplanes.

In an August 1943 issue, Life magazine reported that the Germans called the P-38 “der Gabelschwanz Teufel” (“Fork-tailed Devil”), and for good reason. The fast, versatile Lightning had been designed primarily as a fighter but could also carry two 2,000-pound bombs. Although mostly remembered for its role in the Pacific (where P-38 pilots ambushed and shot down Japanese admiral Isoroku Yamamoto on April 18, 1943, and was the aircraft flown by America’s highest-scoring ace of World War II, Major Richard Bong, for all of his 40 victories), the unique aircraft saw extensive action throughout the war in ground attacks, photo reconnaissance missions, and as a long-range escort. It was powered by a pair of turbo-supercharged 1,600-horsepower engines with counter-rotating propellers. A central pod between its twin booms contained the cockpit and nose-mounted armament of four 50-caliber M2 Browning machine guns and a 20mm Hispano cannon. The technologically advanced fighter did suffer from various teething issues, but its potent arsenal made sure the Lightning packed more punch than most other fighters—and it was especially lethal in the hands of a crack shot like Blumer.

As part of the Ninth Air Force, commanded by Lieutenant General Lewis Brereton, the 367th entered combat for the first time on May 9, 1944. The group initially carried out fighter sweeps over western France before serving as bomber escorts on D-Day, June 6. These “air umbrella” missions continued into the second week of June, followed by fighter-bomber campaigns in response to the enemy reinforcements scrambling to reach Normandy. On June 22, the unit took part in a large-scale attack on the Cotentin Peninsula, where German ground forces maintained a perimeter defense around the fortress city of Cherbourg. The deep-water port had become critically important to the Allies due to recent storm damage to the invasion beachheads. Capturing the ancient harbor would come at a steep price. By the end of the first day, the 367th lost seven pilots and suffered extensive damage to most of its airplanes, grounding all three squadrons for several days.

The airmen adopted the moniker “Dynamite Gang”—a tribute to an air traffic controller named “Dynamite Donovan” who guided scores of wounded warplanes safely back home. After a brief move from Stoney Cross to nearby RAF Ibsley, the fighter group relocated to the advanced landing grounds (ALGs) in France. Their makeshift air base, located next to the small village of Cretteville (ALG-14), featured steel plank runways, Spartan accommodations, and a steady diet of C and K rations. If choking down ham and lima beans wasn’t bad enough, the men also frequently endured assaults by pesky yellow jackets during chowtime.

Appropriately, Blumer christened all of his mounts Scrapiron. (And also added a painting of a naked woman with the word “censored” bannered across her.) He lost three P-38s during his first four months of combat, which included a particularly harrowing bombing mission over German-occupied territory near Caen. Blumer recalled the incident in an army press release: “I was flying at about 6,000 feet when I began to notice the rest of my flight taking evasive action to avoid the flak,” he said. “I began to veer my plane around when a machine gun bullet passed through the cockpit floor, passed through my outstretched legs, and went right through the canopy. I decided to get the Hell out of there in a hurry.” After bailing out of the burning Scrapiron III, Blumer tried to dodge machine gun fire while helplessly dangling from his parachute. He then spent the next eight hours evading capture in No Man’s Land before he finally stumbled onto a friendly patrol. “I was picked up by the British, who gave me a drink of Scotch, and each time I arrived at another station, I received another drink,” he said. “When I finally got back I was pretty plastered.” His report, however, fails to mention how he not only completed the bombing run but waited until his squadron reached safety before ditching the crippled aircraft. His exploits earned him a Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart, and membership into the Caterpillar Club, reserved for people who had to bail out of a damaged aircraft. He also picked a “Winged Boot” for walking back from a mission. More decorations followed.

By late summer 1944, German forces, despite being given plenty of chances, had failed to kill the plucky American called Scrappy, who would soon spearhead one of the greatest dogfights in U.S. military history—an action that earned him the Distinguished Service Cross—and cemented his improbable legacy. On August 25, 1944, the recently promoted Captain Blumer was returning to base after leading a dive-bombing mission on three Luftwaffe airfields in northern France when he received a distress call from Major Grover Gardner, Squadron 394’s leader. His flight had been jumped by more than 40 Focke Wulf Fw-190s approximately 25 miles away. With Lieutenant William Awtrey on his wing, Blumer quickly changed course and radioed back, “Okay, let’s pour on the coal.” After climbing to 10,000 feet, he plunged his P-38 straight into the German swarm, scoring his first kill with a 40-degree deflection shot. The hard-charging American continued to employ the same strategy of climbing and diving as more P-38s joined the fray. In the span of 15 minutes—about the same amount of time it takes for an oil change—Blumer shot down five enemy planes, making him an ace in a single mission.

Awtrey, a soft-spoken South Carolinian, had a ringside seat to the wild melee as he watched what seemed like scores of aircraft explode and drop out of the sky from all directions. He later recounted Blumer’s fifth scalp: “By this time, I was holding my breath,” said Awtrey. “My mouth was dry, and I couldn’t keep my head still. I remember jerking my head around in every direction, waiting for someone to jump Scrappy. As the Nazis began to scatter, looking for safety in flight, Scrappy picked out the last remaining Jerry and dove on him like a hawk. It was so fast I could hardly see it myself. He peppered him with bullets, and the pilot went into a roll, and later I saw him bail out. When I look back on it now, it was like watching a movie.” Remarkably, Scrapiron IV returned to base without a scratch. “It was a pilot’s holiday,” said Blumer. “It was the sort of a day a pilot dreams about and probably gets once in a lifetime.”

Accounts from the Germans illustrate the carnage from the battle’s losing side. Feldwebel Fritz Bucholz of II. Gruppe Jagdgeschwader 6 had logged only a handful of hours in the Fw-190 when he encountered “der Gabelschwanz Teufel” for the first time. “It was utter chaos, with Focke Wulfs chasing ‘Lightnings’ chasing Focke Wulfs,” said Bucholz. “Our initial attack hit the Americans hard, and I saw some Lightnings go down. We might have been new to the business of dogfighting, but with the advantage of the sun and numbers, we held the initiative. Then, suddenly, there seemed to be ‘Lightnings’ diving on us from all directions; now it was our turn to become the hunted.”

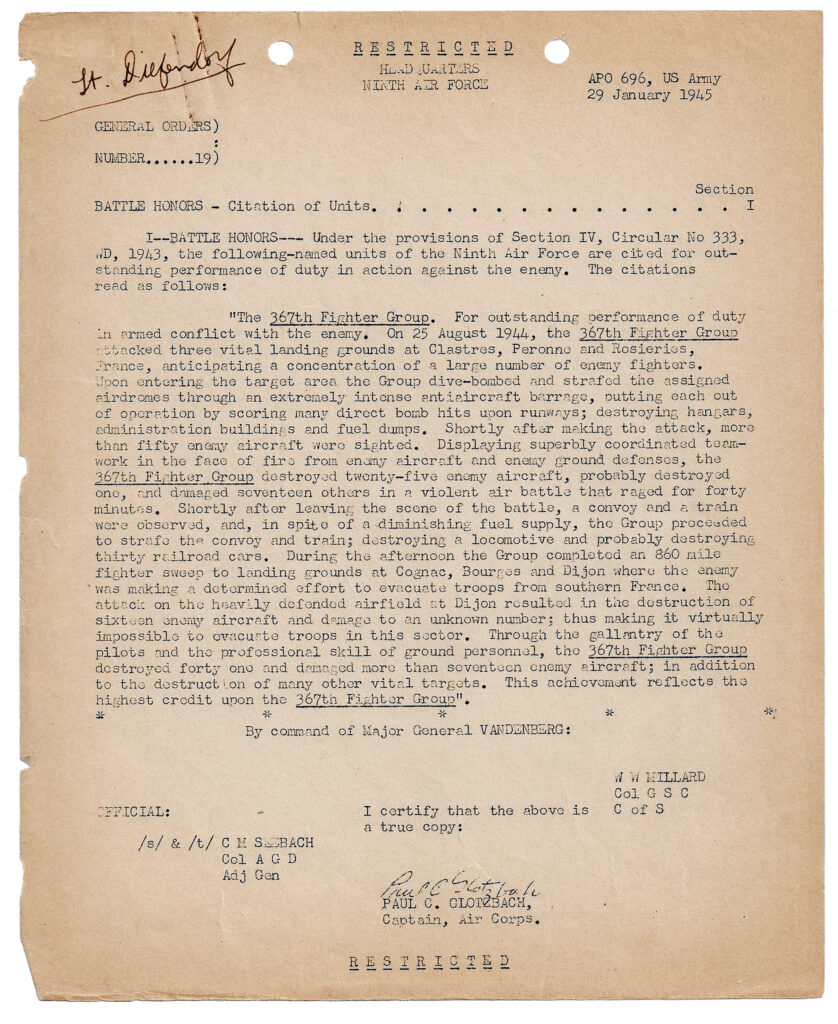

For their efforts, the 367th Fighter Group received the Presidential Unit Citation, the highest possible award for a unit in combat. Of the 33 P-38s engaged, the Americans lost two pilots and had four others bail out over enemy territory. The Germans lost 16 airplanes, with 14 pilots killed, disastrous losses for the unit.

With the U.S. First and Third Armies penetrating deeper into France, the P-38s conducted relentless sorties, attacking trains, destroying railroad tracks, and menacing Nazi airfields. The 367th provided crucial cover during Operation Market-Garden in September 1944, and fought both the Germans and freezing cold weather during the Battle of Bulge that December. American aviators also received high praise from Lieutenant General George S. Patton, who hailed the joint effort as “the best example of the combined use of air and ground troops that I have ever witnessed.” As a token of his appreciation, “Ol’ Blood and Guts” had cases of captured German booze distributed among the fighter groups.

The start of the new year brought several new changes to the 367th, including the transition to the single-engine Republic P-47 Thunderbolts. But after completing more than 100 combat missions and scoring six victories, Blumer—who had been promoted to commander of the squadron on November 10, 1944—ended his tour in mid-January 1945. He then returned to Marysville (renamed Camp Beale) as a major, lending his expertise as a flight instructor. Along the way, he made a pit stop in North Dakota, where the hometown hero visited family and friends. For most returning soldiers, especially those who had repeatedly cheated death, a weekend furlough typically called for rest and relaxation. Unless your name is Scrappy Blumer. Upon arrival at Hector Airport in Fargo, the restless fighter jock noticed a fleet of P-63 King Cobras sitting on the field, designated for a Lend-Lease program with the Soviet Union. Blumer, however, had other plans. He “requisitioned” one of the planes for the remaining 25 miles to Kindred and proceeded to buzz the main street at treetop level, pulling up just in time over his old high school. Not surprisingly, military brass wasn’t the slightest bit amused and severely reprimanded the now famous pilot.

Blumer eventually eased into civilian life and started up a contracting business on the West Coast. But his love of flying never diminished. He bought an old P-38 that had once belonged to the Honduran Air Force and had it fully restored, replete with his trademark “Scrapiron IV” and “Censored” nose art. He flew the celebrated fighter at air shows around the country and, per his custom, could usually be found chomping on a cigar with five more in his shirt pocket. As the years marched on, members of the 367th would occasionally gather at reunions, where conversation invariably turned to stories involving Scrappy. Such as the time he clipped a telephone pole after strafing a train and returned to base with communication lines wrapped around the wings. Or the one about a French gal he took for a ride during a bombing run. Or was she English? No matter. Regardless of the fuzzy details or seemingly impossible odds, they could always agree on one undeniable truth: anything was possible with the man once dubbed “The Scourge of the Luftwaffe.”

Records show that Blumer received 28 decorations for his actions in World War II. The wide range of awards includes a Silver Star, Air Medal with 22 Oak Leaf Clusters, Belgian Croix de Guerre, and a .45 Pistol Expert badge. In 1996, U.S. Representative Peter DeFazio of Oregon presented Blumer with a collection of his medals that had been previously lost or stolen over the years. When asked by a reporter about his thoughts on the ceremony, he tearfully replied, “I think of all my buddies we lost getting them.”

At age 80, having lived a full life—and a sometimes tumultuous personal one that included four marriages—Blumer passed away from leukemia in Springfield, Oregon, on October 23, 1997. He was buried with military honors at Woodbine Cemetery in Puyallup, Washington.