A Cessna O-2’s night reconnaissance mission turned tragic on Christmas Day, 1967. Near the Demilitarized Zone, Maj. Jerry Sellers (pilot) and Capt. Richard Budka (observer) received a radio message about a ground patrol in trouble. Quickly flying towards the area, Sellers turned on his landing lights to direct fire from a nearby AC-47 gunship towards the enemy—putting himself and Budka at high risk. Hit by ground fire, the subsequent crash killed both men. Sellers was posthumously awarded the Air Force Cross. The crew’s bravery allowed the ground patrol to return to safety.

Forward Air Controllers (FACs) were integral to America’s war effort in Vietnam, using various aircraft. One such aircraft—the Cessna O-2—was a modified civilian 337 Skymaster and flew a wide range of missions during the war. Then-Lt. Mike Jackson’s memoir Naked in Da Nang noted: “FACs…plodded along at ridiculously low levels to direct airstrikes, observe troop movements, gather intelligence, and/or choreograph search-and-rescue missions…we were the traffic cops of Southeast Asia, telling everyone where to go, when to go, how to get there, and what to do once they were there.”

Cessna and military aviation have a long history together, as Cessnas were used as World War II trainers and transports. After the war, Cessna designed the single-engine Model 305 with tandem seating for recreational aviation. In turn, the 305s were repurposed by the military into the L-19 “Bird Dog,” seeing service in Korea as observation aircraft.

Redesignated as the O-1 in 1962, Bird Dogs were used extensively in Vietnam and Laos. Their slow speed, limited range, and small ordnance-carrying capacity reduced their effectiveness. The Air Force began searching for more advanced aircraft. At home, Cessna continued developing civilian models such as the 336—first flown in February 1961. This aircraft featured engines in front of and behind the fuselage and twin cantilever booms, which helped avoid yaw if one engine failed.

Re-engineered with improved performance and retractable landing gear in 1964, the 336 aircraft became the Model 337 Skymaster. With two 210-hp Continental engines, these new aircraft had a top speed of about 200 miles per hour and a range of more than 1,000 miles. The Skymaster had a wingspan over 38 feet and were about 30 feet long. The Air Force evaluated over 100 civilian aircraft before deciding in 1966 that the Skymaster, while imperfect, was the best short-term option to replace the O-1. Renamed the O-2 (and earning nicknames such as “Oscar Deuce”), about 450 were deployed to Southeast Asia. O-2s were faster, had longer loiter time over a target, carried more ordnance, and had better instrumentation for night missions compared to O-1s. Two variants saw action: O-2As for FAC missions and O-2Bs for psychological operations.

Military reconfiguration of Skymasters added observation windows, 7.62mm miniguns, LAU-59/A pods holding Folding Fin Aircraft Rockets, armored seats, self-sealing fuel tanks, and stronger landing gear.

O-2 pilots considered the Air Force-designed gunsights ineffective. To improve accuracy, some pilots used a grease pencil mark on the windshield, coordinated with the seat and pilot’s height, as an alternative gunsight.

The U.S. military introduced O-2s into Vietnam beginning in May 1967. This first required getting the aircraft to Asia, which was not a straightforward process. Civilian pilots flew O-2s in flights of four from Cessna’s Wichita, Kansas, plant to Hamilton AFB in California. At Hamilton, the Air Force removed all the seats except the left front and installed extra fuel and oil tanks and an emergency radio. Still flown by civilians, these aircraft island-hopped from California to Vietnam, with flight leaders earning $1,000 and other pilots $800 for the trip, plus airfare home. The Hamilton-Hawaii leg was the longest at about 13 hours flight time; fuel aboard provided for about 14.5 hours of flight, leaving a small margin for navigational error. Years later, an anonymous Air Force pilot wrote: “Civilian misfits ferrying Air Force airplanes across the Pacific to a combat zone? No way!… We began firing off messages to get this idiocy stopped.” The Air Force ultimately assumed responsibility for aircraft delivery.

O-1 pilots stationed in Vietnam received field training for the new aircraft. The 20th Tactical Air Support Squadron (TASS) was the first FAC unit to receive these aircraft and the first O-2 qualified pilot was Maj. James Leatherbee, who described the Cessna as “an ideal plane for FACing.”

For pilots receiving training in the U.S., flight qualification was at Hurlburt Field in Florida (sometimes referenced as “FAC U”). Instruction included Air Ground Operations schooling for coordinating with ground troops, and Fighter Lead-in Training (conducted at Cannon AFB in New Mexico) to ensure that airmen directing attacks near U.S. troops were qualified fighter pilots. Graduates from Cannon were classified as “A” pilots. Those without that training were rated as “B” pilots and relegated to directing attacks only near non-U.S. allied troops. There was an ongoing dispute within military leadership about the tradeoff between fighter pilot training (increasing FAC effectiveness) and the need for aircraft in the sky (given the expanding operational tempo).

Other facets of a pilot’s education included the Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape School at Fairchild AFB in Washington State and the Jungle Survival School at Clark Air Base in the Philippines. After arriving in Vietnam, pilots provided detailed personal information to military intelligence, such as describing their tattoos and scars, to help search-and-rescue teams avoid potential North Vietnamese traps. After arriving in-country, pilots would fly observation missions to become familiar with the terrain and received a check ride with an experienced FAC. They were then deemed to be ready for combat.

Call signs were ubiquitous for FAC pilots, regardless of the type of aircraft flown. For example, “Nail” FACS were assigned to the 23rd TASS and “Covey” FACS were at 20th TASS. These call signs were common self-references that the airmen might use long after their military service concluded.

The Air Force developed an extensive command structure for the FAC effort. The 504th Tactical Air Support Group headquarters had nearly 3,000 personnel by 1968. There were five TASS units: the 19th at Bien Hoa; the 20th at Da Nang; the 21st at Nha Trang and Cam Ranh Bay; the 22nd at Binh Thuy; and the 23rd at Nakhon Phanom in Thailand. These squadrons used about 70 forward operating bases.

Being a FAC was a high intensity job, both in the number of sorties flown and performance requirements on each mission. The 1967 flight manual “FAC Procedures–Target Marking” directed that FACs: “[perform] an area reconnaissance of the target area prior to arrival of the strike aircraft…to confirm the position of friendly forces and study the target terrain, weather, etc. All operations in the target area should be at an altitude above the effective range of small arms fire [approximately 1,500 feet above ground level] unless there is an urgent operational requirement to fly lower. The FAC should have a plan or system but should not establish a set pattern [and] take advantage of sun, clouds, speed, binoculars, etc., to protect and separate himself from the enemy.”

Once assigned to a squadron, FACs would be given specific areas of responsibility (AORs). Pilots were expected to become familiar with their AOR’s terrain and to be alert for changes indicating enemy troop or supply movements. Telltale signs of the enemy would be fresh tracks or smoke from a cook-fire. The movement of water buffalo out of the fields could signify an imminent fire fight—villagers would not want to put these animals at risk.

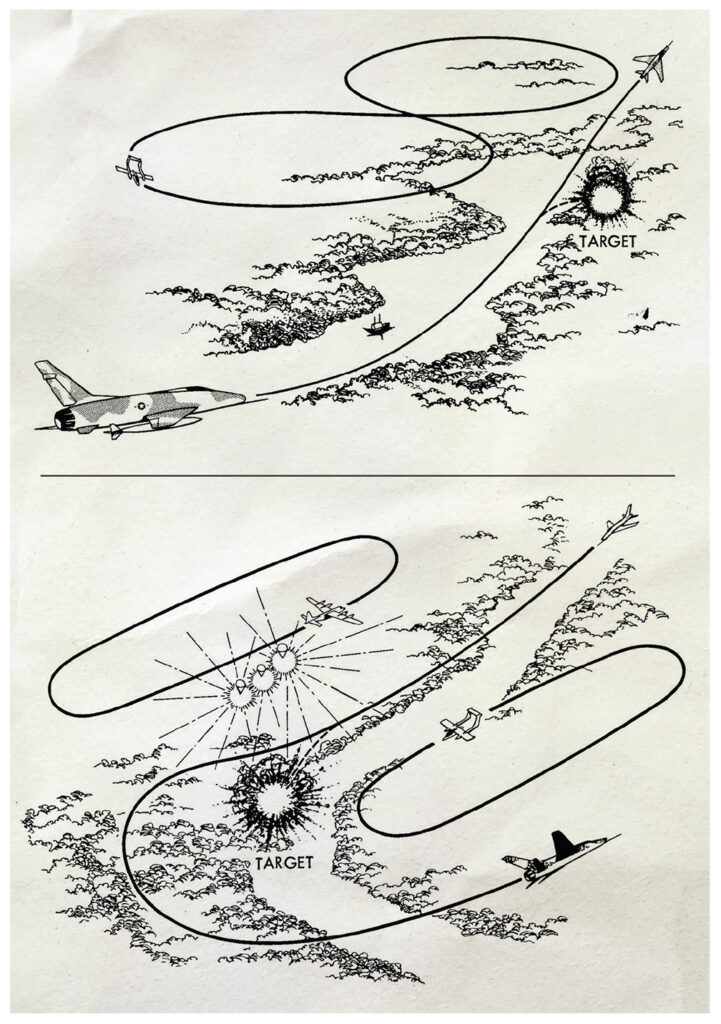

Intelligence, navigators, or maintenance personnel might accompany pilots for daytime missions. FAC missions involved marking enemy positions with white phosphorus (“Willie Pete” in G.I. vernacular) rockets, signaling where the fighters should aim their bomb strikes. If the FAC thought placement was satisfactory, he would call “hit my smoke” as the target for the first bomb. The pilot’s next call would be “cleared hot”—green lighting the first fighter attack. The initial action would be followed by any necessary coordination for additional strikes on the enemy.

Accuracy in marking enemy positions was paramount, as North Vietnamese forces were often close to U.S. and South Vietnamese troops. Given the proximity of the FACs to other U.S. aircraft, often moving overhead at very high speeds, O-2s might have their wing tops painted white to contrast with the jungle terrain. For night missions, O-2s would be painted black and the observer would use a starlight scope to amplify starlight and moonlight. These scopes were effective in illuminating trucks on the Ho Chi Minh trail, leading to the destruction of enemy vehicles.

O-2s were employed for other critical purposes, including assessing bomb damage after B-52 missions and, if circumstances warranted, requesting an attack by the B-52s. It was a risky assignment. The aircraft would circle at low altitude to review the bombing damage while simultaneously avoiding bombs dropped from the higher altitude B-52s.

FACs also supported the insertion/extraction of special forces teams in Laos and Cambodia. They coordinated helicopter and aircraft rescues of downed aircrews. Command Master Sgt. Craig Corbett recounted after bailing out of an AC-119 “Flying Boxcar” (7.62mm and 20mm mini-guns/cannons) gunship near An Loc, South Vietnam: “I turned on my survival radio and heard the pilot of the O-2, whose call sign was Sundog, talking to one of our guys on the ground. Waiting a few seconds…I too made contact with Sundog who said, ‘Sit back, relax, Sandy [the call sign for the rescue teams] is on its way’.…I told myself all would be okay.”

Psychological operations involving O-2B missions included loudspeaker broadcasts and dropping leaflets into enemy positions from a chute installed for this task. The 9th Special Operations Squadron, operating from Da Nang, Phan Rang, Tuy Hoa, and Bien Hoa airbases, engaged in these exercises as part of a broader effort to break the will of enemy soldiers. Broadcasts included a series of pained moans interspersed with Vietnamese music, reminding North Vietnamese fighters of home and the risk of death if they continued fighting.

While these missions were challenging and risky, FAC pilots faced other complications. One was the Rules of Engagement, which provided restrictive, confusing, and contradictory procedures on what could or could not be done in combat situations. Attacking Buddhist temples in Cambodia was off limits, for example. The Communists exploited these constraints by purposely placing weapons in religious temples to shoot at U.S. aircraft. Having to strictly abide by these rules in the face of enemies exploiting them demoralized many American personnel.

Radio communications pilots required expert knowledge, adding to the other challenges they confronted. O-2s were equipped with UHF radios for coordinating with nearby tactical aircraft, FM for communicating with ground troops, and VHF for contacting tactical air control and requesting air support.

Personal safety was a constant concern. Many pilots wore Kevlar flak vests and would sit on a spare vest when airborne for added protection. Flight helmets provided protection against small arms fire. Pilots would be issued personal weapons such as a Smith & Wesson Model 10/Victory Model .38 Special and an M-16. While enemy forces might withhold fire on the FAC if they had not been spotted, all bets were off if the enemy thought they had been seen.

Combat damage resulting from the heavy use of the O-2s required extensive field maintenance. Some maintenance personnel received stateside training from Air Force or Cessna technicians at bases such as Sheppard AFB in Wichita Falls, Texas. For others, on-the-job training was the norm. One airman recalled being given a toolbox, the O-2 instruction manual, and being told “go fix it.” All the same, pilots gave high praise to the quality of their ground maintenance crews.

Courage was never in short supply in the FAC units. Lt. Jackson’s memoir describes an O-2 mission near Hue in mid-1971. Without an observer on board, he was in continuous contact with South Vietnamese forces on the ground (who had rudimentary English skills) while coordinating with nearby F-4 Phantom pilots in dealing with a North Vietnamese attack. Jackson came under heavy ground fire. The ARVN commander on the ground radioed for Jackson to be “careful.” He later wrote: “The ARVN Commander knew that…without me, his unit had a life expectancy of about 20 minutes.” Ultimately promoted to lieutenant colonel, Jackson later became the executive director of the National Aviation Hall of Fame at Wright-Patterson AFB.

Maj. Gerald Dwyer, who served with 23rd TASS, was awarded two Silver Stars in separate actions involving O-2s. In one incident, he was trapped in a ravine surrounded by North Vietnamese fighters after being shot down. He killed three North Vietnamese soldiers with his service revolver and the others fled before he was rescued.

Capt. Thomas Beyer was declared as MIA in July 1968 after he did not return from his O-2 mission in Quang Tin Province. Promoted to major while on MIA status, he was declared as Killed in Action in May 1978. He was awarded the Silver Star with his remains being identified in 2010 and returned home to North Dakota for burial.

These were not isolated incidents, and FAC casualties were high: 84 O-2 crewmen died in combat, part of the 223 total FAC fatalities on all aircraft during the Vietnam War. Two airmen were captured as prisoners of war. Over 100 O-2s were lost to enemy action, and another eight in ground attacks at South Vietnam bases.

There is no doubt that the FACs made a huge contribution to the air war and supporting ground troops in Vietnam. Col. Tom Petitmermet wrote in his memoir, Pretzel 06—Memories of a Forward Air Controller, about his 535 combat sorties in O-2s: “As a FAC I had a level of responsibility that I never came close to again in my future Air Force career. Never again would I have the direct power over the life and death of another person,” as there was virtually no margin for error when calling in airstrikes.

The legacy of the FAC aviators is honored at locations such as Memorial Park in Colorado Springs, Colorado; Hurlburt Field in Florida; and the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. There is also a memorial in Canberra, Australia, commemorating Royal Australian Air Force FAC personnel who served in Vietnam.