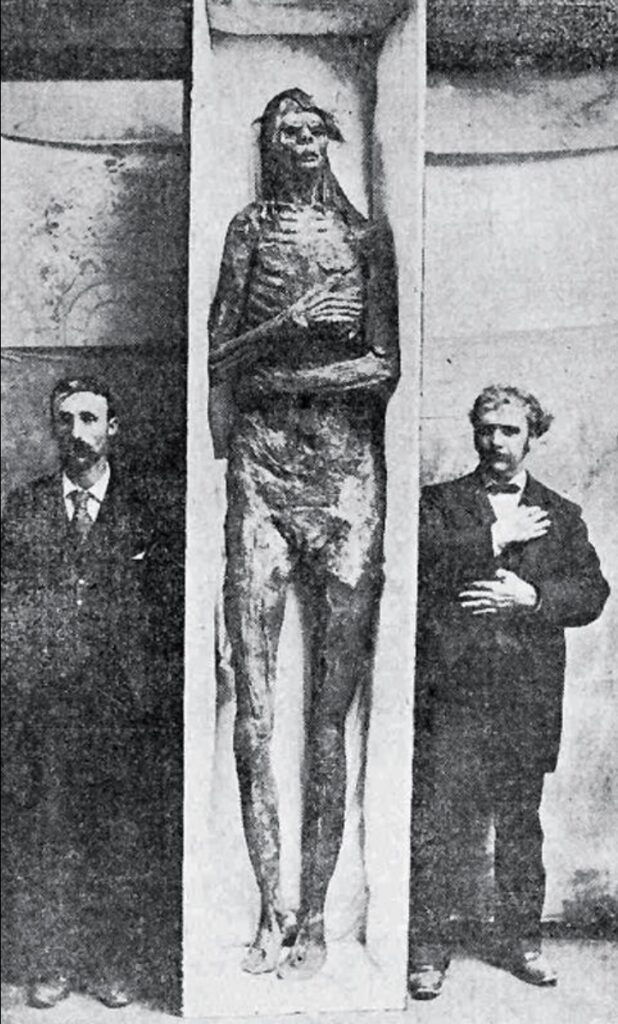

San Diego Giant on display at side show.

In December of 1896, a group of anatomists and anthropologists from Washington, D.C. traveled to a sideshow in Atlanta to examine a mummy known as the San Diego Giant, purportedly the ancient desiccated corpse of one of the tallest men who ever lived.

The previous year, newspapers across the country heralded the discovery of the mummified remains of a Native American man near San Diego. What was so compelling about the find was that the body was about eight feet four inches (2.54 meters) tall-the tallest mummy ever found. The anthropologist that examined him thought he was about nine feet (2.74 meters) tall when he was alive and estimated that he lived about 250 years ago. Rather than being mummified intentionally with natron and resin like in ancient Egypt, the giant had been mummified naturally by the arid environment of Southern California. Not long afterwards the San Diego Giant was featured in the sideshow circuit and exhibited standing up in a ten-foot-long rectangular box to emphasize his towering size.

This significant discovery attracted the interest of museums everywhere, including the Smithsonian Institution. The owner eventually agreed to sell it to the famous DC museum, but the purchase was contingent on a physical examination by anatomists and anthropologists to verify its authenticity. So in 1896, these scholars found themselves at a fair in Atlanta to inspect the enormous mummy. Among them were Professor W.J. McGee, an ethnologist and anthropologist who headed the Bureau of American Ethnology, and Professor F.E. Lucas who worked with at the Smithsonian and was considered one of the best comparative anatomists of his era.

The San Diego Giant looked authentic at first glance. The lips of the shriveled corpse had receded back to expose some of his teeth, and a few of his ribs were visible under his skin. Dr. Lucas, however, became suspicious when he saw that one of the exposed bones had a greasy texture.

According to Stephen N. Byers, forensic anthropologist and author of Introduction to Forensic Anthropology, a greasy feel and look of bones indicates that a relatively short period of time has passed since death. The longer the bones are exposed to air the more dry and porous they become. Therefore, bones belonging to bodies that are hundreds of years old, like the San Diego Giant’s reported age, should be dry to the touch and not feel oily.

After Lucas noticed the grease on the remains, Dr. McGee observed that the distance from the pelvis to the upper end of the femur appeared longer than expected. The scientists, now skeptical, took hair and tissue samples to analyze back at a lab in D.C. These additional analyses revealed that giant’s hair was composed of jute, a vegetable fiber, and the skin was made out of another type of fiber.

Surprising no one, the sale of the San Diego fraud was called off.

An additional examination revealed that the San Diego Giant had been assembled using real human bones as a framework. The bones were cleaned, using ammonia sulphate, and reassembled. Then burgundy pitch and resin were applied to some bandages to create his fake skin. Some believed the giant had been constructed in a factory that specialized in counterfeit mummies and artifacts.

October 21, 1906 issue of the Star Tribune from Minneapolis, MN.

It turns out that at the turn of the 20th century, there were many factories that churned out phony mummies and antiquities to sell to eager collectors who did not care about provenance. These fakes ended up in collections all over the country, including the Mississippi State Capitol.

In the early 1920’s, a man from Yazoo County, Mississippi sold his archaeological collection, consisting of the mummified remains of an Egyptian princess and some Native American artifacts, to the Mississippi State Capitol. The state capitol’s “Egyptian princess” became one of its most popular attractions. But its notoriety was based on a lie and this deception would take more than forty years to be discovered.

In 1969, Gentry Yeatman, a student at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, was working on a paleopathology project of the Department of Archives and History. As part of this project, he offered to x-ray the mummy of the Egyptian princess in the Mississippi Capitol’s archaeological collection and write a detailed report about his findings.

When Yeatman x-rayed what he thought was a mummified corpse, he discovered that the “Egyptian princess” was nothing more than some paper mâché on top of a wooden frame. Even her skull was made out of plaster and her visible front teeth were fake. The only real bones in this dummy were some animal bones in its rib cage.

The “Dummy Mummy” from the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Image credit: Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Because a German language newspaper was found in one of its feet and an 1898 edition of the Milwaukee Journal in its right arm, some thought that forged Egyptian princess was created by German artisans who immigrated to the Milwaukee area in the 19th century.

The “Dummy Mummy” in the Mississippi Capitol’s archaeological collection has become more popular because it’s a notorious forgery. Tourists will line up to view her when she’s on display, and some will sneak into storage to see her when she is not. In 1969, then Archives and History Director, Charlotte Capers wrote, “She may not be a very good mummy, but she is an excellent fake.” Tourists seem to agree.