Following the successful wind tunnel tests of the Vought V-173 low-aspect ratio, flying wing aircraft in late 1941, the US Navy asked Vought to propose a fighter built along similar lines. Charles H. Zimmerman had been working on such a design as early as 1940. He and his team at Vought quickly finalized their fighter design for the Navy as VS-315. On 17 September 1942, before the V-173 had flown, the Navy issued a letter of intent for two VS-315 fighters, designated XF5U-1. One aircraft was a static test airframe, and the other aircraft was a flight test article.

Charles Zimmerman’s fighter aircraft from a patent application submitted in 1940. Although the drawing shows fixed horizontal stabilizers (45/50) and skewed ailerons (34/36), the patent also covered the configuration used on the Vought XF5U. Note the prone position of the pilot, and the guns around the cockpit.

The Vought XF5U was comprised of a rigid aluminum airframe covered with Metalite. Metalite was light and strong and formed by a layer of balsa wood bonded between two thin layers of aluminum. The XF5U had the same basic configuration as the V-173 but was much heavier and more complex.

The XF5U’s entire disk-shaped fuselage provided lift. The aircraft had a short wingspan, and large counter-rotating propellers were placed at the wingtips. At the rear of the aircraft were two vertical tails, and between them were two stabilizing flaps. When the aircraft was near the ground, air loads acted on spring-loaded struts to automatically deflect the stabilizing flaps up and allow air to escape from under the aircraft. The stabilizing flaps enhanced aircraft control during landing. On the sides of the XF5U were hydraulically-boosted, all-moving ailavators (combination ailerons and elevators). The ailavators had a straight leading edge, rather than the swept leading edge used on the V-173’s ailavators. Two large balance weights projected forward of each ailavator’s leading edge.

The XF5U mockup was finished in June 1943. Note the gun ports by the cockpit. The mockup had three-blade propellers and single main gear doors, items that differed from what was ultimately used on the prototype. The acrylic panel under the nose was most likely to improve ground visibility, like the glazing on the V-173. However, test pilots reported that the glazing was not useful.

Zimmerman originally proposed a prone position for the pilot, but a conventional seating position was chosen. The pilot was situated just in front of the leading edge and enclosed in a bubble canopy. Some sources state that an ejection seat was to be used, but no mention of one has been found in Vought documents, and an ejection seat does not appear to have been installed in the XF5U-1 prototype. The cockpit was accessed via a series of recessed steps that led up the back of the aircraft. The acrylic nose of the XF5U housed the gun camera and had provisions for landing and approach lights.

The aircraft’s landing gear was fully retractable, including the double-wheeled tailwheel. The main gear had a track of 15 ft 11.5 in (4.9 m). A small hump in the outer gear doors covered the outboard double main gear wheel. The long gear gave the aircraft an 18.7 degree ground angle. A catapult bridle could be attached to the aircraft’s main gear to facilitate catapult-assisted launches from aircraft carriers. For carrier landings, an arresting hook deployed from the XF5U’s upper surface and hung over the rear of the aircraft. Armament for the XF5U consisted of six .50-cal machine guns—three guns stacked on each side of the cockpit—with 400 rpg. The lower four guns were interchangeable with 20 mm cannons, but the proposed rpg for the cannons has not been found. Two hardpoints under the aircraft could each accommodate a 1,000 lb (454 kg) bomb. No armament was installed on the prototype.

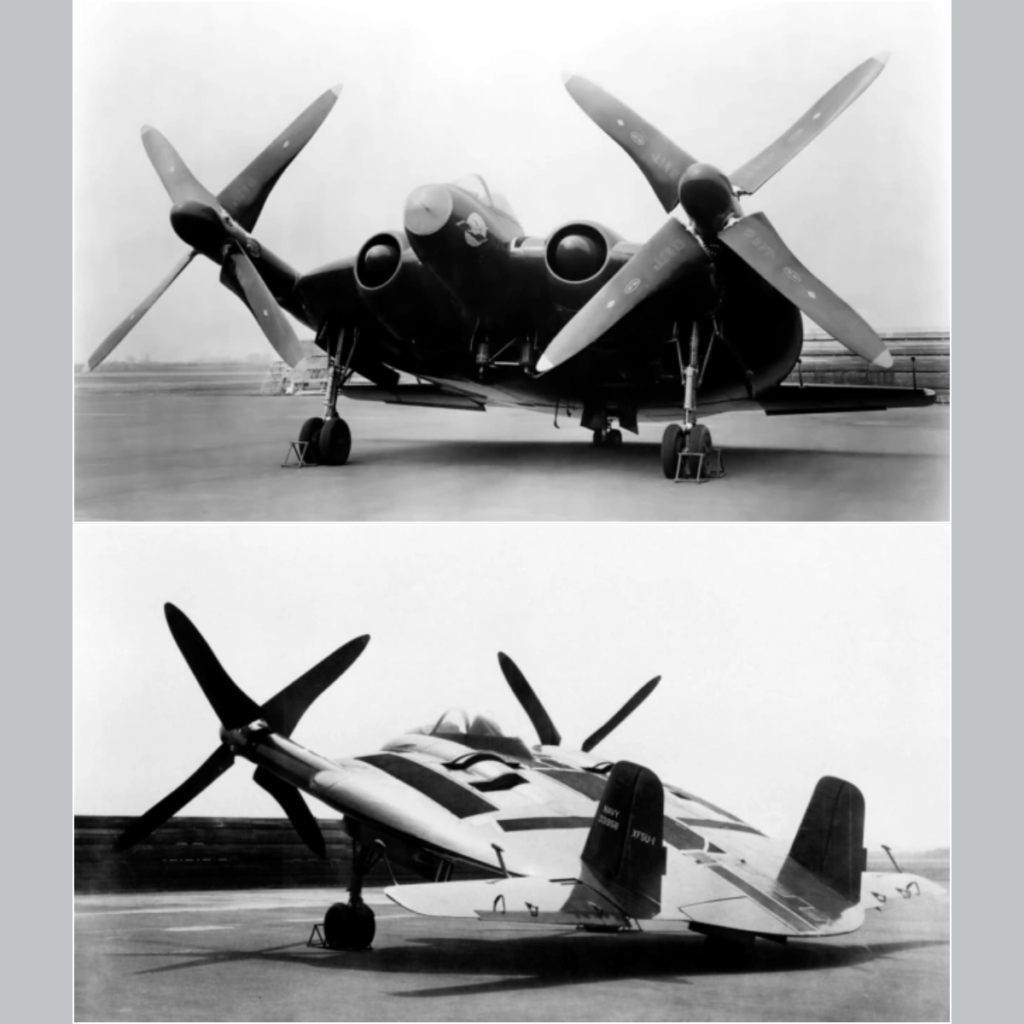

The two XF5Us under construction. The left airframe was used for static testing, and the right airframe was the test flight aircraft. The engine cooling fans and oil tanks can be seen on the right airframe.

Originally, the XF5U was to be powered by two 14-cylinder, 1,600 hp (1,193 kW) Pratt & Whitney (P&W) R-2000-2 engines. It appears P&W stopped development of the -2 engine, and the 1,350 hp (1,007 kW) R-2000-7 was substituted sometime in 1945. The engines were buried in the aircraft’s fuselage, and engine-driven cooling fans brought in air through intakes in the aircraft’s leading edge. Cooling air exit flaps were located on the engine nacelles on both the upper and lower fuselage. An exit flap for intercooler air was located farther back on the top side of each nacelle.

Engine power was delivered to the propellers via a complex set of shafts and right angle gear drives. A two-speed gear reduction provided a .403 speed reduction for takeoff and a .177 reduction for cruising and high-speed flight. With the engines operating at 2,700 rpm (1,350 hp / 1,077 kW) at maximum takeoff power, the propellers turned at 1,088 rpm. At maximum cruise with the engines at 2,350 rpm (735 hp / 548 kW), the propellers turned at 416 rpm.

The complex power drive of the XF5U was the aircraft’s downfall. The system was unlikely to work flawlessly, and the Navy chose to use its post-war budget on jet aircraft rather than testing the XF5U. The inset drawing is from Zimmerman’s patent outlining the propeller drive.

A power cross shaft was mounted between the gearboxes on the front of the engines. In the event of an engine failure, the dead engine would be automatically declutched, and the cross shaft would distribute power from the functioning engine to both propellers. The two engines were declutched from the propeller drive at startup. The clutches were hydraulically engaged, and a loss of fluid pressure caused the clutch to disengage. The engines were controlled by a single throttle lever and could not be operated independently (except at startup).

By November 1943, the ongoing flight tests of the V-173 indicated that special articulating (or flapping) propellers would be needed on the XF5U. Propeller articulation was incorporated into the hub by positioning one two-blade pair of propellers in front of the second two-blade pair. The extra room provided the space needed for the 10 degrees of articulation and the linkages for propeller control. As one blade of a pair articulated forward, the opposite blade of the pair moved aft. To relieve the load and minimize vibrations, the propeller hub mechanism caused the blade pitch to decrease as the blade articulated forward and to increase as the blade moved aft. The XF5U’s wide-cord propellers were 16 ft (4.9 m) in diameter, made from Pregwood (plastic-impregnated wood), and built by Vought. The propellers were finished with a black cuff, a woodgrain blade, and a yellow tip. The pitch of the propellers was controlled by a single lever and could not be independently controlled; the set pitch of all blades changed simultaneously. If both engines failed, the propellers would feather automatically. Construction of the special propellers was delayed, and propellers from a F4U-4 Corsair were temporarily fitted to enable ground testing to begin.

The completed XF5U ready for primary engine runs with F4U-4 propellers. The aircraft was completed over a year before the articulating propellers were finished. Had the propellers been ready sooner, it is likely the XF5U would have been transported to Edwards Air Force Base for testing in late 1945.

The XF5U had a wingspan of 23 ft 4 in (7.1 m) but was 32 ft 6 in (9.9 m) wide from ailavator to ailavator and 36 ft 5 in (8.1 m) from propeller tip to propeller tip. Each ailavator had a span of about 8 ft 4 in (2.5 m). The aircraft was 28 ft 7.5 in (8.7 m) long and 14 ft 9 in (4.5 m) tall. The XF5U could take off in 710 ft (216 m) with no headwind and in 300 ft (91 m) with a 35 mph (56 km/h) headwind. The aircraft had a top speed of 425 mph (684 km/h) and a slow flight speed of 40 mph (64 km/h). Initial rate of climb was 3,000 fpm (15.2 m/s) at 175 mph (282 km/h), and the XF5U had a ceiling of 32,000 ft (9,754 m). A single tank located in the middle of the aircraft carried 261 gallons (988 L) of fuel. The internal fuel gave the XF5U a range of 597 miles (961 km), but with two 150-gallon (568-L) drop tanks added to the aircraft’s hardpoints, range increased to 1,152 miles (1,854 km). The XF5U had an empty weight of 14,550 lb (6,600), a normal weight of 16,802 lb (7,621 kg), and a maximum weight of 18,917 lb (8,581 kg).

The XF5U with its special, wide-cord, articulating propellers installed. Note the winged Vought logo on the propellers. The purpose of the bottles under the fuselage is not clear. The aircraft used compressed air for emergency extension of the landing gear and tail hook. Perhaps that system was being tested. Note that the inner main gear doors have been removed.

A wooden mockup of the XF5U was inspected by the Navy in June 1943. At this time, the mockup had narrow, three-blade propellers that were very similar to those used on the V-173. The XF5U’s complex systems and unconventional layout delayed its construction, which was further stagnated by higher priority work during World War II. The aircraft was rolled out on 20 August 1945 with the F4U-4 propellers installed. Some ground runs were undertaken, but more serious tests had to wait until Vought finished the special articulating propellers in late 1946.

The aircraft started taxi tests on 3 February 1947, but concerns over the XF5U’s propeller drive quickly surfaced. Vought’s chief test pilot Boone T. Guyton made at least one small hop into the air, but no serious test flights were attempted. The test pilots and Vought felt that the only suitable place for test flying the radical aircraft with its unproven gearboxes and propellers was at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Given the XF5U’s construction, the aircraft could not be disassembled, and it was too large to be transported over roads. The only option was to ship the XF5U to California via the Panama Canal. Faced with the expensive transportation request, no urgent need for the XF5U, questions about propeller drive reliability, and the emergence of jet aircraft, the Navy cancelled all further XF5U project activity on 17 March 1947.

This side view of the XF5U shows how the propeller blades were staggered. Note the balance weights on the ailavator, the hump on the gear door, and the slightly open engine cooling air exit flap on the upper fuselage. Strangely, the tail markings appear to have been removed from the photo.

With the original 1,600 hp (1,193 kW) P&W R-2000-2 engines, the XF5U had a forecasted top speed of 460 mph (740 km/h) and a slow speed of 20 mph (32 km/h). The aircraft had a 3,590 fpm (18.2 m/s) initial rate of climb and a service ceiling of 34,500 ft (10,516 m). With a fuel load listed at 300 gallons (1,136 L), the aircraft would have a 710-mile (1,143-km) range. To increase the XF5U’s performance and try to keep the program alive, Vought proposed a turbine-powered model to the Navy, designated VS-341 (or V-341). While it is not entirely clear which engine was selected, the engine depicted in a technical drawing closely resembles the 2,200 hp (1,641 kW) General Electric T31 (TG-100) turboprop. The estimated performance of the VS-341 was a top speed of 550 mph (885 km/h) and a slow speed of 0 mph (0 km/h)—figures that would allow the VS-341 to achieve Zimmerman’s dream of a high-speed, vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft.

Rear view of the XF5U shows padding taped to the aircraft to protect its Metalite surface. The engine cooling air exit flaps are open. The intercooler doors have been removed, which aided engine cooling during ground runs. Note the tail markings on the aircraft.

The XF5U intended for flight testing (BuNo 33958) was smashed by a wrecking ball shortly after the program was cancelled. The XF5U’s rigid airframe withstood the initial blows, but there was no saving the aircraft; its remains were sold for scrap. At the time, the second XF5U (BuNo 33959) had already been destroyed during static tests.

Zimmerman’s aircraft were given several nicknames during their development: Zimmer’s-Skimmer, Flying Flapjack, and Flying Pancake. It is unfortunate that a radical aircraft so close to flight testing was not actually flown. Zimmerman continued to work on VTOL aircraft for the rest of his career.

To bring the XF5U into the jet age, Vought designed the turbine-powered VS-341. The aircraft had the same basic layout as the XF5U. Note the power cross shaft extending from the gearbox toward the other engine.