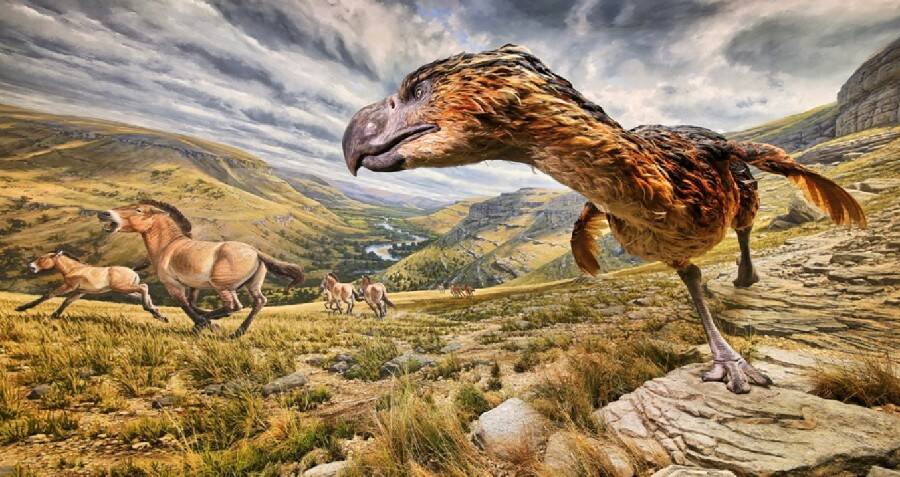

For much of the Cenozoic Era, terror birds dominated South America and hunted with hatchet-like beaks — until they went extinct about 2 million years ago.

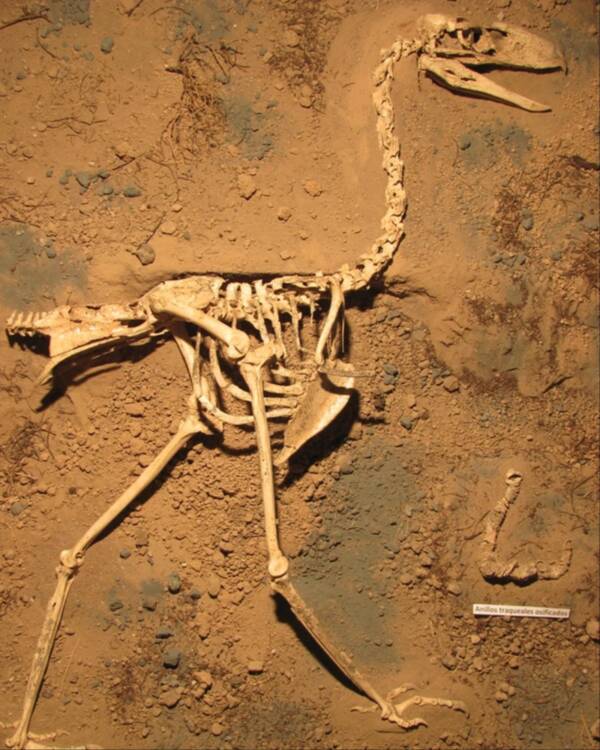

M. Taglioretti and F. ScagliaAn incredibly intact skeleton of a species of terror bird called Llallawavis scagliai, first discovered in 2010.

The ancient world was full of terrifying monsters. But while most know a thing or two about the dinosaurs, who ruled the animal kingdom until their extinction about 65 million years ago, few know about the predators who took their place: the aptly-named terror birds.

Officially called Phorusrhacids, terror birds rose to prominence roughly 60 million years ago in South America. Though numerous different species have been discovered, the largest stood 10 feet tall and weighed more than 1,000 pounds. Fast and with a sharp beak, they swiftly became an apex predator.

Yet, like the dinosaurs, the reign of the terror birds eventually came to an end. These enormous predatory creatures met their match around 2 million years ago when the continents of North and South America finally connected.

The Discovery Of Phorusrhacids

According to an article published in Cambridge University’s Journal of Paleontology, the terror bird was first described by an Argentinean paleontologist named Florentino Ameghino in 1887. He and his brother found an “incomplete mandible” in the Santa Cruz Formation in Patagonia.

Darwin’s Door reports that Ameghino named his discovery Phorusrhacos longissimus, and came to believe that it once resembled something close to an eagle or a hawk. However, further discoveries suggested that the terror bird was more closely related to the seriema, a South American bird.

Getty ImagesA South American Red-legged Seriema. These birds are believed to be terror birds’ closest living relatives.

Since then, some 20 different terror bird species have been discovered. Some, like Llallawavis scagliai, discovered in 2010, are relatively small and stand just four feet tall. But others, like Kelenken guillermoi, discovered in 2004, are much more terror-inducing. Kelenken stands an awe-inspiring 10 feet tall and likely weighed more than 1,000 pounds.

According to the paleontologist Luis Chiappe, who described Kelenken in 2007, its enormous skull is “the largest known skull for terror birds.” He told Wired, “As a matter of fact, it’s the largest known bird skull, period.”

So what were these terror birds like before they went extinct?

Inside The Reign Of The Terror Birds

Between 60 million and two million years ago, terror birds ruled over South America, using their size, speed, and powerful beak to reign over the continent.

According to the National Audubon Society, terror birds couldn’t fly, but they could reach speeds of up to 60 miles per hour on the ground. What’s more, they likely used their face as a “hatchet” against other animals.

“I mean, we know that a little parrot, a cockatoo, can take your finger out,” Chiappe told Wired. “Imagine what a bird like this could have done, the damage it could have done with just a strike of this massive skull and beak. So that’s obviously one very easy way of imagining this is how these animals killed their prey.”

Describing Kelenken to NPR, he added: “With the size of the skull, imagine the damage that skull could have done just by hitting something.”

Stephanie Abramowicz/Natural History Museum of Los Angeles CountyMost paleontologists believe that the terror bird used its giant, sharp beak to kill prey.

That said, some scientists have suggested that the terror birds were more bark than bite — and that they weren’t predators at all, but rather herbivores. According to Wired, German scientists studied the calcium isotope composition in terror birds’ bones and found that they were more similar to herbivores than carnivores.

Nevertheless, Chiappe told Wired that he believes that the terror birds were predators. “Maybe [the terror birds’] bite force was not strong enough,” he said, “maybe they were limited to preying on certain animals, but that doesn’t make them, in my opinion, a non-predatory bird.”

Scientists may not know exactly what the terror birds ate. But they do have a better idea of what these giant prehistoric beasts sounded like. Researchers were able to reconstruct the birds’ inner ear after the discovery of the well-preserved Llallawavis scagliali in 2010.

Federico Degrange, the co-author of a study on Llallawavis scagliali, explained to the BBC that he and other researchers compared the terror birds’ inner ear canal to living species. They found that it probably sounded like an emu or an ostrich. The Audubon Society describes their likely call as a “low bellowing.”

“We are able to say that terror birds had low-frequency sensitivity – so it seems reasonable to suggest that they also produced low-frequency sounds,” Degrange told the BBC.

He added: “But we will be never sure that that tone corresponds to the song of the Llallawavis because we also need a structure that was not preserved — the syrinx, the singing structure that birds have. It seems that in Llallawavis, it was made of soft tissue, and was not preserved.”

So why did this giant, powerful (and loud) bird go extinct?

What Happened To The Terror Birds?

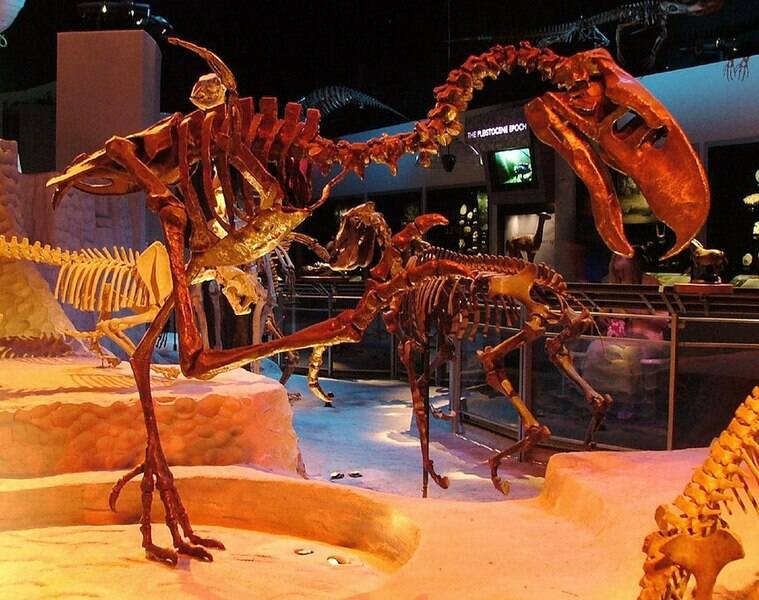

FunkMonk/FlickrThe reconstructed skeleton of a terror bird at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

As far as paleontologists today know, terror birds started to disappear around two million years ago. Many researchers believe that their decline, and eventual extinction, lined up with the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, which connected North and South America for the first time.

There’s clear evidence that terror birds migrated north, as their fossils have been discovered in Texas and Florida. But then, some suspect, the terror birds met their match in the form of predators like jaguars and sabertooth cats, who also migrated south. No longer the top predator, they began to die out.

“So they had to face new competition for the same resources,” Chiappe explained to Wired. “And that, combined with perhaps changes in climate, they may not have been able to cope with and that may have impacted their hunting strategies, probably drove them to extinction.”

But not everyone thinks that the terror birds’ extinction was that simple. Degrange believes that the discovery of Llallawavis scagliali has complicated things because Llallawavis suggests that the birds were more diverse than researchers previously knew.

“The previous idea was that they kind of lost the competition against placental mammals when placental mammals arrived in South America,” he said. “But that was based mainly on the low diversity of [terror bird] species that were known at the time. But Llallawavis is showing the opposite.”

In other words, he explained, paleontologists needed to start thinking about other reasons why terror birds went extinct.

For now, many mysteries about the terror bird exist. Was it truly a terrifying carnivore — or merely a large, bellowing herbivore? Did the merging of North and South America doom its existence? Or were more complicated factors at play, like climate change?

There’s certainly more to learn about this fascinating prehistoric creature. But one thing is for sure — a terror bird like the 10-foot Kelenken guillermoi would be a terrifying sight to behold.