French author Pierre-Antoine Courable and his Belgian cohort Jean Dewaerheid have brought the force of serious research to the seven decade-old legend of Allied bomber crews hitting fake German airfields with fake British bombs. Now, they are looking for former Commonwealth airmen who might have been party to the shenanigans which have become urban legend.

In what could easily be the finest and boldest example of death-defying and cheeky nose-thumbing during the Second World War or any conflict for that matter, bomber and intruder crews of the Royal Air Force and USAAF are reputed to have bombed the Luftwaffe’s decoy airfields and dummy aircraft, not with high explosives or incendiaries, but with nothing more than dummy bombs made of wood, and painted with the smug remark “Wood for Wood”… all just to make a point.

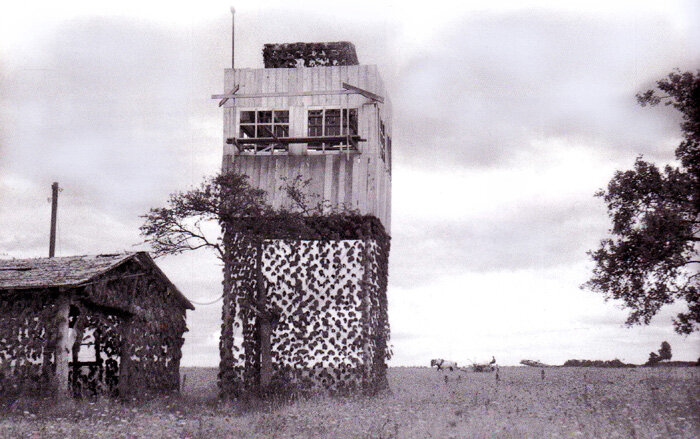

Throughout all theatres of war, during the Second World War, from China to Holland to Kent, air forces, phsy-ops units and logistics people constructed dummy targets such as airfields, factories, truck parks, convoys and even ships, out of wood, canvas, burlap, or inflatable rubber. The decoy airfields were often populated with dummy aircraft and vehicles of such high quality, that even low flying recce aircraft with photographic equipment would have hard time telling the difference between the dummies and the real thing. The decoy airfields and dummy aircraft served several purposes simultaneously. They confused snooping enemy aircraft and hence planners as to the number of aircraft available to the opposing forces as well as to their displacement. They provided decoy targets for enemy bombers which, if attacked would prevent real aircraft from being destroyed. Often, these airfields were built near real airports in the path of attacking aircraft in the hopes that they would then drop their bombs and strafe the dummies, thereby saving the real aircraft.

If a decoy target did indeed induce attackers to drop their ordnance ineffectively, those that created the decoy would have certainly worn smug looks afterward… perhaps the deception would have been the source of much hilarity that night in the pub or brasserie. If the attackers later learned that they had been duped, they would have felt foolish indeed. So, if a dummy airfield was detected through spies or recce photography, it made sense to simply avoid it favour of the real target or to ignore it, leading the enemy to continue the ruse and waste the energies of Luftwaffe personnel. That would make sense for war planners and decision makers far from the daily meat grinder that was the war. For weary and frustrated pilots and aircrews, a chance to mock the efforts of their enemies, to make a point about who was winning, to complete a “skit” that would be the source of pride, soaring morale and back-slapping camaraderie from pub crawls to the fifty-year reunions of the future, seems to have been too good to pass up.

You are standing along the edge of a large open field in Belgium, which, over the past three weeks, you and your fellow Luftwaffe airmen have laboured and transformed into a decoy airfield. You are on edge yourself. Two days ago, an RAF Mustang had made a low level pass right over the heart of the field. Everyone could see the round camera window on the side of the aircraft. Everyone knew he had seen.

Just as you finish pushing a massive wooden Ju-87 Stuka tail first into the surrounding forest, you hear the sound of approaching aircraft. An obergetfreiter next to you shouts Achtung!! Mücken!!! You look to the south of the field and see a pair of dark Mosquito fighter-bombers arcing in from the west. You and your pals run headlong into the wooded periphery of the airfield as the two wraiths thunder in. Your heart is racing – out of fear for your life and out of joy that you have tricked the bloody British or Canadians, or whom ever, into believing this was a real field. You can hear the whoops and cheers of your mates who also realize this at the same time.

Hiding behind a large tree, you peer out through the branched and catch a glimpse of the side of the fast moving pair, their bomb doors open, ripping down the far edge of the field where six Stuka replicas sit parked, tails in the forest. You smile… “Stupid Brits!”, you think, “We fooled you”. You watch from half a kilometer away as several oddly slender bombs drop away from the two Mosquitoes and tumble weirdly to the ground. Instinctively, you flinch from the impending explosion, withdrawing behind the tree. But there is nothing. Maybe there was a sound… but it was not an explosion. It sounded like a series of heavy thumps.

You look around to your friends. Everyone shrugs. After a few minutes, you see other airmen across the field walking near where the bombs were dropped. You cross the field to where several men are standing. One feldwebel is holding one of the bombs. Warily you look it over. It is not made out of metal. In fact it is simply a four foot length of wood… a log with the remains of four crude wooden fins at one end and a sharp end that reminds you of a pencil. There is writing down one side… “Wood for Wood”. The English-speaking sergeant translates “Holtz für holtz”. For a moment everyone lets this soak in. Soon they are all laughing and so are you. But as they chuckle away and collect the other logs, you realize something. All your work has been for naught. The English, they are on to you. Above all… you have a nagging thought which, for the first time, begins to gnaw away at the far reaches of your mind – you cannot possibly win this war.

The story of the wooden bombs, a legend that just won’t die, has long been held to be true by unspecified witnesses and often retold through here-say and third hand accounts. Many “show-me-the-proof” historians have disdainfully discounted the legend as apocryphal, unsubstantiated poppycock and urban legend. The multitudinous aviation forums are battlegrounds where defensive-sounding “believers” duke it out with self-appointed historians who cannot believe a story unless it is written down in pilots’ log books, Squadron ORBs, Wing diaries or found in the archives of the Imperial War Museum. The would-be nay-sayers of this former urban legend cite primarily the idea that it would be better to not tip off your opponent to the fact that you know about the phony airfield by dropping fake bombs on it. They state that somehow this would compromise your intelligence network on the ground and tell the enemy how much you know. But, I say, it would have much the same result if you were seen to overfly the airfield with recce aircraft and then never return with real bombs. Either way, the enemy knows you know. By dropping fake bombs on an fake and usually undefended mock-up of an airfield, you simply made the Germans look and feel foolish, your pilots and navigators flew a milk run and had a laugh and a skit and in the end you simply gained the upper hand. I for one have no trouble believing this, especially after reading the recently published book, Wood for Wood – the Riddle of the Wooden Bombs by Pierre-Antoine Courouble.

French citizen and researcher Pierre-Antoine Courouble had one source for his belief in this story of British humour and derring-do – one that did not have a written record, was not found noted on a squadron ORB or pulled from the shelf of a musty archive. It was the strong and honest voice of his father, a man he loved and trusted. Here is what Courable says about the first time he heard the story:

“The first time I heard about the famous “legend” of the wooden bombs was during the summer of 1973. I can still picture the scene. My father was driving the family Citroën GS and we were going from Lesquin to Templeuve where what was to become our family home was being built. I was born in Lesquin, at No.1 of rue Sadi Carnot, the very street in which the Germans had requisitioned the neighbouring houses to lodge Luftwaffe pilots, one of whom was Joseph Priller, the Luftwaffe ace with 101 victims to his credit. I had spent my childhood with the noise of the engines from the neighbouring airfield in the background. A fan of anything to do with flying, I was fascinated by the stories about World War II. We had just passed the trees by the Fretin Fort when my father told me a story he had never mentioned before.

“Do you know that not far from this road the Jerries installed wooden planes?”

“No, I didn’t, and why wooden planes?” I asked him.

“To make the Allies believe that they still had planes when they hadn’t got any left!”

“I see. I suppose they also used them to deceive the enemy into bombing false targets,” I replied in a knowledgeable tone to prove to my father that I knew something about military subjects.

“Yes, but it didn’t work! The deceiver was out-done. The only bombs that the English dropped on those wooden planes were wooden ones! And they’d painted ‘Wood for wood’ on them!

I was fascinated by this tale. My father said that he had got the details of the story from Mr Cardon, a farmer in Lesquin, who had actually seen this amusing example of nose thumbing.

That is how he came to hear of this “great story””.

In 2009, Courable published his book which, for this writer, finally proves with absolutely thorough research and the first-hand accounts witnesses that everyone said never existed that the wooden bombs for wooden targets skit actually happened.. and many times. A year later, the long-sought star witness for Courable’s thesis, a Luftwaffe pilot by the name of Oberstleutnant Werner Thiel came forward and was video-taped corroborating the story of the Allied air force’s joke.

Thiel was born in Dillenburg in 1923, and became Leutnant pilot in the Luftwaffe in 1943. He was detached at the Luftkriegschule Werder (An aerial warfare school near Potsdam) where he was the witness to the the dropping of a dozen dummy wooden bombs on fake wooden airplanes deployed there by his Luftwaffe. The bombs were marked with the painted words “Wood for wood”! This extraordinary testimony from a German officer was video-taped on 28th December 2010 by Pierre-Antoine Courouble. Here is a remarkable extract from that interview

Werner Thiel: I was born on the 24th of August 1923 in Dillenburg, in the center of Germany. I joined the Luftwaffe in 1942. After training courses in France (first in Romorantin, then Angers and later Le Mans) I was posted in October 1943 at the airfield of Werder, near Berlin. In those days I also worked at the false aerodrome of Borkheide that was equipped with a runway. We were living in a kind of container, nearby two air-raid shelters. These were in fact small bunkers where we could find refuge when the Allies bombed Berlin. At the end of October 1943, the air raid warning alarm went off. We put the lights on from the false runway and moved the decoy planes.

Courouble: How many decoy airplanes did you use?

Thiel:Maximum ten, I would say. They were made of wood and netting. A few nights before, we noticed reconnaissance missions, so we were prepared for the raid. We heard the planes coming …

Courouble:Sorry to interrupt you once again, but how many people were in charge at this dummy airfield?

Thiel: I would say a dozen soldiers. Not more.

Thiel: … Like everybody else, we were afraid of these air raids. We heard the planes flying above us but this time nothing happened. At dawn, we left our shelter with cautious steps. We dreaded time bombs. We didn’t believe what we saw: they bombed us with wooden bombs! Six to ten wooden bombs laid on the ground, all with painted in white « Wood for Wood ».

Courouble: What about the body of those bombs? Was it hollow?

Thiel: They were made of solid wood. One of us was a carpenter and managed to use this excellent wood material to build new frames for the enlarged aerial pictures that were going to decorate our austere surroundings.

Courouble: Did you use all these bombs for that purpose?

Thiel: Yes, all of them. We were not the only guardsmen. Our colleagues were full of admiration and we exchanged some of our pictures for cigarettes or food …

Courouble:Do you remember what you thought at that time? Did you have any idea about the use of these wooden bombs?

Thiel:We thought it was meant as a joke. Something like “Look how stupid you are. You built a dummy airfield. We saw it and it’s not worth dropping a real bomb!”

(Thiel takes his glass and looks at the camera)

Thiel:I drink to the health of all pilots in the world and more particularly to the American colleagues. I would be extremely happy to meet one day the American pilot who dropped those wooden bombs. Prosit!

Sadly, this year Werner Thiel passed away in Germany, but his account as a Luftwaffe pilot who worked on one of the German dummy airfields and witnessed the wooden destruction of wooden aircraft, proves that Courable’s thesis is correct – Bomber Command and then Eighth Air Force crews made mockery of the Luftwaffe’s efforts to fool them by dropping wooden bombs on wooden airplanes.

Though Courable’s book is published and though Theil’s testimony puts to rest the legend of the wooden bombs, he and Dewaerheid are still looking for witnesses and in particular any allied aircrew or ground crew who might have participated in these “attacks”. The two know that time is running out to find men who flew these missions or who built the wooden bombs or “armed” the aircraft and would appreciate any eye-witness accounts to help build a permanent and comprehensive archive of this particularly humourous part of the history of the Second World War.

“Attrappen” — German Dummy Aircraft

Decoy Aircraft of Other Nations

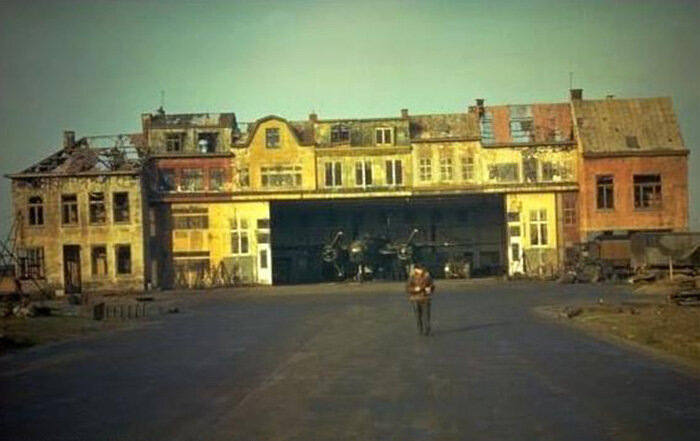

The science and art of camouflaging targets such as airfields to hide from prying eyes or, as in the case of the Wood for Wood story, to make them seen, believed and attacked by the enemy has existed as long as there has been warfare. The practice was utilized by all sides during the Second World War to sow disinformation, to hide value targets and to trick the enemy into committing assets and expending expensive ordinance in a fruitless attack on a piece of folk art. The most important part of creating a ruse such as a decoy airfield was the manufacture and deployment of decoy aircraft. These decoys had to be good enough to elicit a response such as an immediate attack by marauding intruders, or to convince battle planners who relied on photo interpretation that this was a target of high value, worthy of attack.

The degree to which this practice was carried out varies. Many dummy aircraft were simply constructed by local labour–crude and functioning at the basest of levels–while some were so believable as to guarantee attack if discovered. It seems that there are not many photos of these faux aircraft that survive today. Most are poor quality digital images, with the best having been taken by victorious ground forces after overrunning the fields where the aircraft were. After reading “Wood for Wood”, I spent some time on the web researching and grabbing images where I could. What follows is an album of images of dummy/decoy aircraft which shows the efforts taken by all sides.

Not all airfields were disguised to be seen

While, as we have seen, some forms of camouflage/disguise were designed to bring you in close and beg you to attack, others were created for the opposite reason – to be unnoticed, to be ordinary, to be anything but an important military target. Hangars became chateaus, maintenance buildings became town homes, and runways were cow pastures. What follows here is an album of the creative efforts of the Luftwaffe to disguise their actual airfields. While the phony airfields provoked the RAF intruder pilots to drop faux bombs on faux airfields, the following facilities, when discovered, received the real deal bombs.

The Decoy Aircraft Business is Still going Strong

Despite the excellent quality of satellite reconnaissance photography available to opposing forces today, high grade, inflatable dummy aircraft are still deemed effective and are being deployed in attempts to fool the enemy.